Overall summary

Our judgments

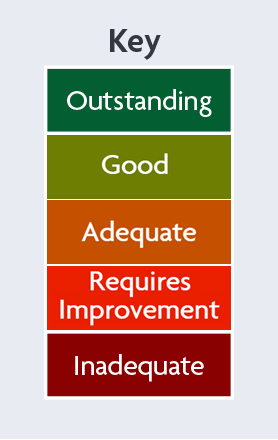

Our inspection assessed how good the City of London Police is in 11 areas of policing. We make graded judgments in 10 of these 11 as follows:

We also inspected how effective a service the City of London Police gives to victims of crime. We don’t make a graded judgment in this overall area.

We set out our detailed findings about things the force is doing well and where the force should improve in the rest of this report.

Important changes to PEEL

In 2014, we introduced our police effectiveness, efficiency and legitimacy (PEEL) inspections, which assess the performance of all 43 police forces in England and Wales. Since then, we have been continuously adapting our approach and during the past year we have seen the most significant changes yet.

We now use a more intelligence-led, continual assessment approach, rather than the annual PEEL inspections we used in previous years. For instance, we have integrated our rolling crime data integrity inspections into these PEEL assessments. Our PEEL victim service assessment also includes a crime data integrity element in at least every other assessment. We have also changed our approach to graded judgments. We now assess forces against the characteristics of good performance, set out in the PEEL Assessment Framework 2021/22, and we more clearly link our judgments to causes of concern and areas for improvement. We have also expanded our previous four-tier system of judgments to five tiers. As a result, we can state more precisely where we consider improvement is needed and highlight more effectively the best ways of doing things.

However, these changes mean that it isn’t possible to make direct comparisons between the grades awarded in this round of PEEL inspections with those from previous years. A reduction in grade, particularly from good to adequate, doesn’t necessarily mean that there has been a reduction in performance, unless we say so in the report.

HM Inspector’s observations

The City of London Police, in addition to its local responsibilities to police its force area, is the national lead for fraud and cybercrime. It also manages the national reporting system for fraud across England and Wales, called Action Fraud.

The force provides this national leadership effectively across all 43 police forces in England and Wales, despite having limited ability to influence how each police force chooses to respond to the threats from these two crime types.

We found that the force is committed to improving the service victims receive and increasing the effectiveness of Action Fraud. It has highly-trained staff who support this national responsibility effectively. And these staff are dedicated to leading and

co-ordinating the local and national policing response to fraud and cybercrime.

The force is developing victim care facilities and a tasking process to assess the threat, harm and risks posed to victims and communities. This will allow better prioritisation, allow crimes to be allocated to the correct resource for investigation, better support investigators and improve the service to victims. The work the force does to target fraud and cybercrime is admirable and should be highlighted.

I have some concerns that the force’s focus on providing an effective leadership response to these national threats isn’t matched by the same level of focus on local policing issues. The force needs to make sure the resources, training, and emphasis on local implementation is improved.

The force is good at engaging with and treating the public with fairness and respect

We found that the force is good at involving and working with communities, including small businesses. It has an effective independent advisory scrutiny group which also helps the force understand what is important to the communities it serves. We also found that it has improved the way it uses its powers, such as stop and search, to make sure its use is appropriate and proportionate, with effective supervision and oversight. The force has developed innovative ways to make sure that its use of stop search powers is fair and respectful.

The force is good at responding to the public

We also found that the force is generally good at how it responds to calls for service from the public. It has effective processes for dealing with the vulnerability of victims, from the first contact. Notably this works well in how the force responds to domestic abuse incidents. It is also effective at building evidence-led prosecutions when victims feel unable to support a prosecution.

The force needs to get better at how it prevents crime and antisocial behaviour

We found that the force struggles to make effective use of its neighbourhood teams. These teams receive little direction or training, and the wider force is often unaware of its role and what it can achieve. Neighbourhood policing in the City of London Police is generally underinvested, with too few staff, and the staff it has are regularly posted to other police duties, away from neighbourhood policing duties (abstraction).

The force must improve its strategic planning, organisational management and how it makes best use of its resources

The force doesn’t have systems in place to effectively understand all its current demand, in some cases because of a lack of accurate data and analytical support. It now uses an analytical tool, called Power BI, which is welcome. But alone this will not address the issues. The force’s incomplete understanding of its demand means its plans for future development are unlikely to be as accurate as they could be.

Across several areas of policing services, we found a distinct lack of analysts. This is limiting the force’s ability to understand demand, respond effectively to threats and drive performance more generally. The force must review how many analysts it needs and make sure the numbers reflect the need.

I would also encourage the force to effectively link its understanding of demand to a workforce plan. This will make sure it has the officers and staff able to respond to the workload the force faces. We also found substantial numbers of vacancies in the corporate services function (such as HR and data analysts), which is reducing the overall effectiveness of the force.

I also have some concerns about the quality of the force management statement. This needs to improve so it more accurately reflects the total demand placed on the force, and more comprehensively assesses its workforce and other assets. The force will then be in a stronger position to make informed decisions about how it will change to meet expected future demand.

The force can do more to improve how it manages high-risk offenders and suspects

The force has shown itself to be effective in managing offenders involved in low-risk offences, such as volume crime (any crime that through its sheer volume has a significant impact on the community and the ability of local police to tackle it). But it needs to improve how it manages high-risk offenders, such as registered sex offenders (although numbers are low in the City of London).

Matt Parr

HM Inspector of Constabulary

Providing a service to the victims of crime

Victim service assessment

This section describes our assessment of the service victims receive from the City of London Police, from the point of reporting a crime through to the outcome. In completing this assessment, we reviewed 90 criminal investigations.

When the police close a case of a reported crime, it will be assigned what is referred to as an ‘outcome type’. This describes the reason for closing it.

We also reviewed 62 cases which had one of the following outcome codes assigned to it:

- A suspect was identified, and the victim supported police action, but evidential difficulties prevented further action (outcome 15).

- A suspect was identified, but there were evidential difficulties, and the victim didn’t support, or withdrew their support for police action (outcome 16).

- A community resolution was applied.

While this assessment is ungraded, it influences graded judgments in the other areas we have inspected.

The City of London Police doesn’t manage emergency call handling itself, but when it receives the information the force deals with calls well

The Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) carries out the initial call handling for incidents reported by telephone, including 999 calls. The information is then passed to call handlers in the City of London Police. From this point we found that generally the correct information was recorded, the service provided was professional, and the information was assessed, via THRIVE, to manage and mitigate vulnerability in most cases.

The City of London Police uses an old IT system called CAD for recording and managing incidents reported to them by the public. Because it is out of date, it isn’t easy to research the information held on it. This makes it difficult for call handlers and others to easily identify repeat callers or victims, or those who may be vulnerable. We did find that the force has found a way to improve how it flagged records relating to those who may be vulnerable, to try and overcome the problems caused by the IT. The force accepts the CAD system is old and plans to upgrade it, although the timing for this isn’t yet known.

In most cases the force responds promptly to calls for service

The force has published response times for how quickly it should attend to different types of calls for service, based on prioritisation. During our inspection we found that on most occasions, the force responded to calls appropriately, within set timescales and with suitable resources.

The force makes sure that investigations are allocated to staff with suitable levels of experience

The force has a policy to make sure crimes are allocated to appropriately-trained officers or staff. Its policy also establishes when a crime isn’t to be investigated further. This is in line with national expectations.

Generally, we found the City of London Police allocated recorded crimes for investigation according to its policy. In nearly all cases, the crime was allocated to the most appropriate department for further investigation.

The force doesn’t always carry out effective investigations, but most are timely

In most cases, the City of London Police carried out investigations in a timely way, but relevant and proportionate lines of inquiry weren’t always completed. Not all investigations were well supervised, but victims were updated throughout. In most cases, victim personal statements were taken, which gives victims the opportunity to describe how that crime has affected their lives.

When victims withdrew support for an investigation, the force considered progressing the case without the victim’s support, particularly for domestic abuse crimes. This can be an important method of safeguarding the victim and preventing further offences from being committed.

The Code of Practice for Victims of Crime requires forces to carry out an assessment of the needs of victims at an early stage. This assessment helps to determine whether the victim needs additional support. The force didn’t always carry out this assessment and record the request for additional support.

The force can improve how it records victims’ wishes prior to closing an investigation

The force should keep a record of the victim’s views when a suspect has been identified but the victim either doesn’t support police action, or withdraws their support for it. During our inspection we found that the force is failing to record why victims are withdrawing their support for investigations. This means it can’t satisfy itself fully that the victim’s wishes are being considered before investigations are closed.

When a suspect has been identified and the victim supported police action, but evidential difficulties prevent further action, the victim should be informed of the decision to close the investigation. Victims weren’t always informed of the decision to take no further action and to close the investigation. However, the force used this outcome appropriately on most occasions.

In some cases, offenders can be issued with a community resolution. A community resolution should be appropriate for the offender and the nature of the offence, and the views of the victim should be considered and recorded. In most of the cases we reviewed, the offender and the circumstances of the case meant that it was suitable to use this outcome. We also found that the victim’s views were considered.

Engaging with and treating the public with fairness and respect

The City of London Police is good at treating people fairly and with respect.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to treating people fairly and with respect.

The force should extend its unconscious bias training to its whole workforce

In 2019 we gave the force an area for improvement, which was to provide unconscious bias training to its entire workforce.

The force told us that 28 percent of its officers and staff are yet to be trained in unconscious bias, via the National Centre for Applied Learning Technologies package. This is disappointing given the opportunities provided by the pandemic to work remotely. We will continue to monitor the force’s progress in completing this area for improvement.

The force is good at engaging with communities to understand what is important to them

The force involves its communities in several ways. Because it is a relatively small force, covering a small area, it can tailor how it works with communities, for example with businesses and young people, more effectively. It has a good relationship with its independent advisory scrutiny group (IASG), and a cluster of local community groups. This helps the force to understand community concerns. It also uses social media well. For example, the force broadcasts the professional standards and integrity committee via YouTube to reach a wider audience.

Local policing teams have struggled to visit schools as often as they want to. This is because of vacancies in the team. But from January 2023 there will be a dedicated schools officer in all local schools. This officer will be responsible for helping co-ordinate a personal, social, health and economic education programme for schools.

The force works with strategic partners and charities to provide early intervention activities for vulnerable groups. This is to prevent them becoming involved in, or becoming victims of crime. During our inspection we found that this work helps the force better understand community concerns.

While community engagement is positive, it could be improved with a comprehensive engagement strategy

The force doesn’t have an engagement strategy. While the way it involves its resident, business and transient communities is positive, such a strategy may help to enhance its understanding of what is important to the people it polices. It would also provide officers and staff with a framework to help make sure the way they work with these groups is as effective as possible.

The force is improving its fair use of stop and search powers

The City of London Police provides stop and search training to student officers and informs officers about changes in legislation or practice. Most of the officers we spoke to told us they feel well trained. Most felt, however, that refresher training would help them maintain current standards.

During our inspection, we reviewed a sample of 104 stop and search records from 1 January to 31 December 2021. Based on this sample, we estimate that 83.7 percent (with a confidence interval of +/- 7.0 percent) of all stop and searches by the force during this period had reasonable grounds recorded. This is a statistically significant deterioration compared with the findings from our previous review of records from 2019, where we found 93.7 percent (with a confidence interval of +/- 2.9 percent) of stop and searches had reasonable grounds recorded. Of the records we reviewed for stop and searches on people from ethnic minorities, 25 of 29 had reasonable grounds recorded.

More can be done to make sure all reasonable grounds are detailed enough to understand how appropriately these powers are used. We also looked at some body-worn video (BWV) recordings of stop and search encounters. These show that most searches are of a good standard.

The supervision, oversight, and governance of stop search powers is comprehensive and includes external scrutiny

Every stop and search form completed by officers is reviewed by sergeants in conjunction with the BWV footage. This means that sergeants can offer remedial advice and guidance to their teams at the point of submission. The force has introduced five further reviews and tests to create a comprehensive oversight of how stop and search powers are used. These include:

- dip samples by the second line manager;

- thematic reviews by the strategic lead;

- an independent randomised review of forms and BWV by the IASG;

- a review of stop and search data; and

- a review of complaints data and trends.

The scrutiny in place is critical to support fair and appropriate use of stop and search powers. Each layer of review will provide educational actions and help officers to improve the use of these powers.

Currently a lack of analytical support is undermining the processes for stop search and use of force

While the force’s governance and oversight look impressive, it is being undermined by a lack of analytical support to each area. We saw that actions raised by the IASG to understand why there had been a rise in disproportionality weren’t addressed for five months. This delay was because of a lack of data to help the force assess the reasons for this rise. We found that governance meetings weren’t being provided with current data or trends. This made decision-making and scrutiny more difficult. The force needs to address this urgently to ensure the governance it has put in place is supported by the correct information.

Use-of-force reviews and governance are improving, but they aren’t as mature as those for stop and search

The force is trying to develop the same process of review and scrutiny for use-of-force submissions that they have in place for stop and search. The plan is for supervisors to review all cases while watching BWV footage. These reviews are proving difficult and time consuming because of the technology used for completing the forms. We found 300 use-of-force events over 2 months that were awaiting supervisor review. The force is aware of this. The reduction of this backlog and the overall management of this process is a priority action within the force performance meeting.

The other areas of review mirror stop and search scrutiny. These processes have only recently been introduced by the force. If the technology problem for initial review by supervisors can be solved, the governance and review process will be the same robust process as we found for stop and search.

The independent scrutiny of stop and searches and use of force is improving

The force has improved its external scrutiny of stop and search and use of force. There are regular meetings which are independently chaired, with community representatives involved. At each meeting, several stop and search encounters are reviewed by watching redacted BWV footage and examining stop and search records. The force has recently adopted a methodology to include stop and searches that have a use-of-force element, so both can be reviewed independently. Members are surveyed and this information is used to give feedback to the officers and their supervisors about stop and search. It is in its early stages, but the force hopes this approach will provide a better understanding of how these powers are used and the effect they have on the community.

Good

Preventing crime and anti-social behaviour

The City of London Police requires improvement at prevention and deterrence.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to prevention and deterrence.

The neighbourhood team lack direction and feel that the role is undervalued

The neighbourhood team currently consists of 9 police officers and police community support officers with responsibility for the 12 areas across the force. We found that the number of officers in the neighbourhood team isn’t enough to cope with the workload they face. These officers are also expected to undertake other duties when required (abstractions), such as policing demonstrations and other major events. This takes them away from their neighbourhood policing role. The lack of officers and routine abstractions, along with frequent absence of supervision has led to some officers feeling demotivated and undervalued. We also found that the force doesn’t routinely monitor and comply with its own abstraction policy. And some managers expressed a concern that they didn’t have control over the level of abstractions.

We were told that the force has a plan to significantly increase the number of officers in this team.

The force needs to understand the demand faced by the neighbourhood team

The force currently has little understanding of the demand faced by the neighbourhood teams. This is reflected in the lack of supervision or monitoring of their activity. There is a performance framework but there has been no governance or accountability for neighbourhood performance through any structured meeting. We believe that clear leadership in this area will provide much needed direction for the team. Some understanding of the demand on the team should follow from this.

The force works well with partner organisations to tackle crime and vulnerability

The force works with the Safer City Partnership which is responsible for implementing the Safer City Strategy. The partnership has a good understanding of community issues, which are raised at a local level via ward panel meetings. The force could further enhance engagement with a detailed strategy to guide neighbourhood teams.

The night-time economy in the force area has grown rapidly in line with the easing of COVID-19 restrictions. The force has dedicated an analyst within the licensing team to work alongside partner organisations to develop preventative activity such as reducing alcohol-related violence and vulnerability. Using crime data and applying the Cambridge Crime Harm Index, the force was able to identify hot spot locations for violence linked to the night-time economy. This allowed patrols to concentrate their activity. The force told us that a trial of this approach between 21 July and 24 September 2022 resulted in a reduction in the overall harm caused by crime during this period. In addition, Operation Reframe is a partnership initiative which aims to make public areas a safer place for women by providing support and interventions. This activity would benefit from evaluation to establish if it has led to a reduction or displacement of crime.

The force uses academic support from University College London to help with its problem-solving initiatives. In addition to this, the force is using evidence-based policing, such as successful multi-agency Operation Luscombe, which was used to tackle street begging in the City of London.

The force is undertaking some good work to engage with young people

The force is invested in providing a Police Cadet programme. It has over 30 cadets who undertake a bespoke development plan and take part in the Duke of Edinburgh scheme. Other youth engagement initiatives include working with Amazon, who helped a group of young students increase their digital skills. The force became involved to develop the relationship between police and young people and increase trust and confidence.

We also found that the City of London Police has limited engagement with schools in its force area. This is in part because the force has limited neighbourhood resources and no schools liaison officer. We also heard that some schools are reluctant to engage with the police in prevention and intervention work. To try and address this, the force has committed to creating a schools liaison officer in January 2023.

The force prioritises the prevention of fraud nationally

The force is the national lead for fraud and cybercrime. It co-ordinates and prioritises prevention activity in relation to economic and cybercrime throughout the UK. The National Economic Crime Victim Care Unit provides victims with crime prevention advice in line with the Code of Practice for Victims of Crime, with enhanced services for vulnerable victims.

Requires improvement

Responding to the public

The City of London Police is good at responding to the public.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force responds to the public.

The force provides a good response to incidents. It uses specialist resources to help first responders to support and safeguard victims

The City of London Police attended 38 of 39 incidents we reviewed within set timescales. We often listened to a call and could hear the patrol arriving while the initial information was still being obtained. This is excellent for victims and helped by the geographic nature of the force. We found that first responders were often supported at complex scenes by specialists, such as detectives and digital forensic experts. The use of experts at this initial stage helps to provide better decision-making at crime scenes and maximises evidence-gathering opportunities. It also helps first responders to learn about the best opportunities for evidence gathering and so improve their skills and knowledge. This could be one reason why the City of London Police has a consistently high proportion of crimes resulting in positive outcomes, such as charges, or out-of-court disposals.

The force offers the public a range of channels to report incidents

The City of London Police provides its community with several ways to report incidents or contact them. And the force is effective at managing calls for service from the public. We found that online reporting had increased, and the force has resources that provide a timely assessment of the information and any vulnerability of victims. This process is well supervised in the force control room. We also found that other avenues including 101, direct business lines and the use of social media mean that businesses, residents, and visitors to the City of London can easily contact the force.

The force does not answer 999 calls. This is managed for them by the MPS, as BT can’t differentiate where the demand originates from in London. The force has recently approved a new service level agreement with the MPS which will allow it to attend governance meetings to test and challenge performance in call handling. However, once the call is transferred to the force, call handlers and supervisors in the force control centre use THRIVE to assess vulnerability. We found that the force allocated the correct resource to attend and deal with the incident in all 75 cases we reviewed.

The force understands risk and vulnerability in calls from the public

We found that the force consistently used THRIVE from initial contact with a caller, to identify and assess vulnerability, and consider safeguarding needs. This is applied in all forms of contact and was well supervised within the force control room. Risk assessments are consistently used and recorded in the incident. Examples show that any delays in attendance or changes in response are decided according to risk and vulnerability. This is positive and gives us confidence that call handlers are providing the right response to incidents. We also found examples of dispatchers using specialist resources to help manage the response, and any vulnerability found in the calls they receive. In our last inspection we found that because the force IT is outdated, that it wasn’t flagging vulnerability well. We are pleased to find that this has improved, with more incidents involving vulnerability being flagged on the IT system. In the year ending 31 March 2022, the force flagged 8.9 percent of all incidents as involving vulnerability, compared to 0.4 percent in the previous year. The delay in installation of the new CAD system, shared with the MPS, continues to make the force less able to identify and mitigate vulnerability, so it is good to see that alternative measures have been put in place.

The force could improve how it uses information and intelligence to respond more effectively

The force needs to improve how its intelligence function supports the initial response to services within the City of London. We found that the force was reviewing its intelligence function (i24), because it wasn’t working in the way it had been intended. We also found that the force didn’t have enough analysts working in intelligence to meet the demand. When i24 was implemented, the plan was to have an intelligence officer working with the call handlers to provide them with better information about victims, offenders, and locations. This was to allow call handlers to provide more detailed information to first responders being sent to incidents. This function is not being provided – staff in the force control room assist where they can. But services and management of vulnerability would improve greatly if this gap was closed, and more detailed information and intelligence made available to officers attending incidents.

The lack of relevant information is hampering leaders in briefing response teams and setting patrol locations more effectively. This is currently being done well using professional judgement via the daily morning meeting structure. It would be enhanced with an analytical view of demand and resources, to hotspot and direct resources more effectively.

The force is inconsistent in how it manages golden hour actions and handover of information to investigators

We found that, after prompt attendance, the application of golden hour principles and handovers of information to investigators was inconsistent. In 12 of the 79 cases we reviewed, there wasn’t evidence that all appropriate investigative opportunities were taken. Staff stated this was mainly down to the experience of the attending response officers. It was clear that the standard of investigation depended on who attended, as there was no clear handover expectation or process. We found that some of the temporary and newly promoted sergeants who were supervising uniform officers, were inexperienced and lacked the necessary skills and knowledge to effectively supervise their investigations. This is compounding the problems.

In 15 of 76 cases we reviewed, there wasn’t evidence of effective supervision, providing direction and advice to the investigator via the crime investigation plan. The lack of experience in the response teams has coincided with increased recruitment of officers from the Police Uplift Programme (PUP). The force is struggling to find sufficient tutors to manage the initial education of new staff. We encourage the force to address this area by introducing training on golden hour principles that sets clear standards for attending officers, is well supervised and that ensures all actions are recorded. The force will then have some assurance that all evidential opportunities are maximised.

The force works in partnership with mental health services effectively, to support the vulnerable and protect them from further harm

In partnership with the local health trust, the force offers a mental health triage service which sees mental health practitioners attending calls with officers. This service operates across the force, mainly during peak periods. Having practitioners working with officers helps them to deal better with members of the public who have mental health issues. These practitioners can access health records, provide professional advice and support police action. We saw a positive example of how this expert advice and support has reduced the demands on the force, by safeguarding key prominent London bridges that were being used for suicide attempts. This means that people with mental health problems get an appropriate service when they call.

Officer and staff well-being in the force control room and on response teams is understood and prioritised

During our inspection we visited the force control room and spoke to control room staff and response teams. The control room staff told us that their workload and working hours are manageable. The environment that has been developed and supportive supervision offer the staff a balance between meeting demands and managing well-being.

Officers on response teams said they had noticed a clear change in focus from the force, since the appointment of the commissioner and her new strategic leadership team. The main priority was now people and victims. Most of the staff we spoke to felt that their well-being was seen as important and reported that their line managers genuinely cared and supported them in any way they needed. The force has also created a well-being room that staff can use when needed.

Officers and staff are aware of the trauma risk management process. Generally, we found that the sergeant rank was under new pressures and felt that they were struggling with their well-being and work/life balance. Officers of differing ranks told us that the sergeant rank is under capacity and being propped up by temporary promotions. With the PUP bringing an increase of staff, it has also increased supervision demands across all areas of policing. This means expectations on response sergeants has increased, and these demands would appear likely to remain high for the foreseeable future. This is an area the force is actively looking into and it was reviewing current ratios to make sure there are enough sergeants to supervise constables.

But, overall, we saw a positive picture of how workforce well-being is managed in the control room and response teams. Supporting officers and staff well helps them to stay in work and provide essential first contact service to the public.

Good

Investigating crime

The City of London Police is adequate at investigating crime.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force investigates crime.

The force has robust governance and policies in place to ensure complex investigations are of a high standard

The force senior leadership team seeks to continuously improve the quality of investigations. There are thematic objectives to drive investigation quality and to get appropriate outcomes for victims of crime. The governance in complex crime investigation teams includes a daily crime meeting and a fortnightly tasking group. Strategically there are crime standards, and crime scrutiny groups that test the quality of investigations on behalf of victims. These generate clear educational actions for individuals and teams to improve services. These governance groups feed the overall force performance meeting. This provides clear, directional, and visible leadership in this area.

The management and governance of volume crime offences could be improved

Most failings in the investigative process were in burglary and other neighbourhood crime investigations. These crime types are predominantly investigated by the volume crime unit and force resolution centre staff. These staff don’t have the same standard of accredited training, known as professionalising investigations programme training, as other investigators.

We also found that their supervisors lacked the training and experience to provide real support and guidance. To compound this, investigations weren’t subject to the same intrusive processes as more complex investigations. This has led to inconsistent standards. We encourage the force to ensure the same standards and scrutiny are maintained across all investigations.

Most investigations are allocated to people with the right skills and are effective

We found that 78 of 80 investigations we reviewed were allocated to teams with the right skills to investigate them and 66 of 80 were effective, with positive outcomes for victims. Review processes are undertaken by detective inspectors and above to help to maintain standards, and help staff learn what is needed to close investigative gaps.

The force recognises the importance of forensic evidence and is investing to meet future demand

The force has invested in improving forensic services to support investigations. The high-tech crime unit assists investigators by attending scenes with specialist equipment to obtain evidence. It works with the investigator to prioritise digital forensic submissions. This makes the whole process more efficient and effective. As a result the force has no queues in digital forensic submissions. It also plans to provide digital storage in the Cloud. This will allow easier access to data for investigators and prosecutors. This means the force is preparing itself to meet future demands in this area well.

The force provides a quality of service to victims of crime but could improve the recording of victims’ needs assessments

As part of our victim service assessment, we assessed if the force had provided a good service to victims in line with the requirements of the Code of Practice for Victims of Crime. We found that in 69 of 72 relevant cases we reviewed a victim contract was agreed and adhered to by the investigator. The force maintained good communication with the victim, providing them with regular and key updates in 61 of 65 cases. We also found (indicated as innovative practice) that the force regularly seeks evidence-led prosecutions in domestic abuse-related cases. And the force arrested a suspect at the earliest opportunity in 30 of 32 relevant cases. All this good practice helps in safeguarding and supporting victims throughout the investigation.

The force should address how it is carrying out and recording initial victims’ needs assessments. We found that in 31 of 52 cases we reviewed these hadn’t been properly recorded. So, while the service to the victim overall is of a good quality, the recording of the initial needs assessment and the revisiting of this assessment throughout the investigation needs to improve. This will show how and where victims need support, and it will make it easier to test in governance processes.

Well-being is seen as a priority. However, this isn’t being realised in investigation departments due to a lack of capacity

Well-being is a core consideration in the force. Most of the workforce told us that their immediate supervisors take welfare seriously and review their workload commitments. However, most staff also told us that supervisors often couldn’t actually do anything to help them, mainly due to the workload demands and shortages of staff.

The criminal investigation department and public protection unit carry out the most complex investigations in the force. Even under this additional pressure, 32 of 40 investigations we reviewed handled by these units were effective. Vacancies in expected staff numbers were found in most ranks and specialisms within the criminal investigation department and public protection unit. These vacancies need addressing as a matter of urgency. Otherwise, there will be a negative effect on the good performance and well-being of staff. We have seen a plan to fill the gaps, and this is discussed further in the strategic planning chapter.

Adequate

Protecting vulnerable people

The City of London Police is adequate at protecting vulnerable people.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force protects vulnerable people.

The force has improved how it identifies vulnerability

Since our last inspection, the force has improved its systems and processes to identify and manage vulnerability. All incidents are subject to THRIVE assessment from initial contact until resolution, including key points in investigations. Our victim service assessment found that the force had embraced online reporting and there was a thorough and timely assessment of each case, using THRIVE, by control room staff.

The force can improve how all staff manage vulnerability

There are clear policies outlining who has responsibility for safeguarding vulnerable people and victims. But we found an old-fashioned culture where most frontline staff referred to the management of vulnerability as the PPU’s problem. We gathered evidence to suggest that when PPU staff weren’t available, response and neighbourhood staff felt they weren’t supported in their decision-making. We found this disappointing as this view doesn’t match policies, which make clear the identification and management of vulnerability are everyone’s responsibility. This is further underlined by the PPU staff’s excellent management of evidence-led prosecutions for domestic abuse victims, highlighted in the investigations section of this report. Yet we found the same opportunities weren’t being explored in investigations undertaken by other departments. The force should address the training and education of all staff to ensure that the culture of it being everyone’s responsibility to manage vulnerability translates into practice.

The force doesn’t always consider other powers to support vulnerable victims or manage persistent offenders

The force doesn’t use some of its of protective powers, such as domestic abuse protection notices and domestic abuse protection orders as well as it could. The force makes limited use of these partly because of the relatively low number of domestic abuse offences. But in the six cases we reviewed, only one showed a detailed reason as to why they shouldn’t use ancillary orders. With the remaining five cases there was no record to show this was even considered.

There is a lack of awareness among staff about their ability to proactively disclose previous and relevant violent offending history to potential vulnerable victims. The force made no disclosures under the Domestic Violence Disclosure Scheme (‘Right to know’) between 1 October 2017 and 31 March 2022. This means opportunities to safeguarding victims and prevent further offences could be missed. In developing the response to managing vulnerability, staff and supervisors need educating in the use, recording and management of powers. This also needs to be incorporated into force governance processes.

The force works effectively and proactively with partners to reduce vulnerability

When looking at the local multi-agency safeguarding hub and multi-agency risk assessment conference processes, and partner working more generally, we found that most referrals were dealt with appropriately and well. We found a positive example of good partnership working following the arrival of 800 Afghan refugees in a location in the City of London. Due to already strong working relationships, officers and multi-agency safeguarding hub partners were able to provide education, support, and guidance to all very effectively. Positive feedback around working practices and how referrals are managed was provided by partners. The relationship in child and adult services with the City of London Police officers is excellent, providing good and structured support when required, which achieves a fast and proactive approach to safeguarding if needed.

The force has developed good preventative activity to support vulnerable groups and reduce violence against women and girls in the night-time economy

Since the lifting of COVID-19 restrictions, the City of London Police has seen a rise in offences linked to the night-time economy, including sexual offences and violence against women and girls (VAWG). The force has appointed a VAWG lead who co-ordinates the force response via an action plan that aligns with the four national VAWG pillars. They have also developed good preventative activity to support these vulnerable groups and prevent offending. This includes integrating the national initiative Ask for Angela which is designed to help people who feel unsafe or threatened in a venue to ask for help. The force also has its own local operation called Reframe, where the force deploys with strategic partners and charities to hotspot locations within the night-time economy to support and educate potential victims. They have also introduced hotspot pulse operations designed to reduce high-harm violence. They developed this idea from the Cambridge Crime Harm Index. This showed a clear reduction in harm during the operation.

The force can do more to understand how it supports vulnerable groups and manages hidden vulnerability

While the force’s preventative activity is commendable, we found that a lack of detailed analysis meant that outcomes and the effectiveness of these initiatives was difficult to judge. As a result, the force isn’t clear if the policing activity, including that with partner organisations, is managing to prevent, reduce or simply displace crime. Greater investment in analysis would also help to identify where to plan further operations and crime prevention activity.

The force is developing its use of Microsoft Power BI software to help officers and leaders to better understand crime patterns and vulnerability. And while this approach has merit, it is no replacement for detailed analysis with associated recommendations to tackle identified problems. We encourage the force to develop its overall analytical capability to improve its focus on tackling hidden vulnerability.

Adequate

Managing offenders and suspects

The City of London Police requires improvement at managing offenders and suspects.

Main findings

The above areas for improvement relate to the City of London Police’s management of the most dangerous offenders. These are thankfully a small minority in the force area. In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force manages all other offenders and suspects. And in general, we found this to be effective.

The force has sound processes and governance to ensure suspects are apprehended promptly

The force has a policy for managing wanted persons. High-risk suspects are discussed at daily management meetings, with patrols directed to trace and arrest them. Lower-risk suspects are managed by the investigating officer. In those cases, once initial inquiries are complete, the suspect is circulated as wanted on the police national computer; however, the investigating officer remains responsible for apprehending the suspect. The offender management meeting occurs monthly. At this meeting all outstanding suspects are monitored, and supervisors hold officers to account for inquires to trace them. The force has enough officers and staff to ensure that suspects are arrested promptly. During our victim service assessment we found that the force made an arrest at the earliest opportunity in 30 out of 32 cases.

Released under investigation and bail are used appropriately

The force has a standard operating procedure for bail and released under investigation (RUI), with an inspector’s authority required for bail. We examined a sample of custody records, which indicated that decisions about granting bail and RUI were appropriate. Safeguarding of the victim is considered and rationale for decisions documented for those released on bail. There was less rationale recorded for decisions to RUI. This is particularly relevant to the volume crime unit which uses RUI in most of its cases. The force should satisfy itself that all decisions, especially when using RUI, are appropriate. This is particularly important with the changes to the Bail Act coming into force, where there is now more emphasis on seeking bail, and in particular bail with conditions, to prevent further offences and protect victims and witnesses.

The custody manager examines all cases, which become RUI at the end of the bail period. This is to ensure any risks are managed and the decision is correct.

The management of voluntary attendance is improving

We were pleased to see that the force has undertaken a self-assessment of the way voluntary attendance is managed. It found that the oversight and scrutiny of voluntary attendance was inconsistent. As a result, it has updated standard operating procedures and provided training to improve in this area. It plans to complete a further dip sample soon to ensure this activity has produced the required improvements.

The force is developing an integrated offender management scheme

The force has recently recruited into an integrated offender management (IOM) role. There is some development required and the force needs to identify where the role sits within its structure, so that support and accountability are provided at the right level. The force is considering including IOM within neighbourhood policing so that the function works more effectively in a problem-solving arena. In order to manage persistent offenders effectively, the IOM scheme should prioritise the development of a cohort of offenders likely to reoffend, as they currently don’t have one.

Foreign national suspects are managed effectively

The force has a standard operating procedure in relation to managing suspects who are foreign nationals. It has developed a checklist of requirements when a foreign national is taken into custody. It has designated a role to provide scrutiny of the relevant custody records to ensure all actions are completed and that it can work effectively with the Immigration Service. This practice has become more consistent with the introduction of the custody cadre, where officers are dedicated to custody roles and therefore develop expertise in this area.

Requires improvement

Disrupting serious organised crime

The City of London Police requires improvement at tackling serious and organised crime (SOC).

Understanding SOC and setting priorities to tackle it

The CoLP is the national lead force for fraud. It receives approximately £30m per year from the Home Office to provide this function. It co-ordinates prevention and investigation of fraud and cybercrime activity with private industry and law enforcement partners nationally.

In July 2022, the CoLP had identified 43 SOC threats. Thirty-three of these threats were classified with a primary crime type of fraud. The force has experienced difficulties in gathering intelligence from the business community regarding non-fraud crime types.

The CoLP has defined priority threats from organised crime, and its control strategy highlights the main fraud issues

The force has prepared a strategic assessment and associated control strategy. The following are defined as its priority threats from organised crime:

- illicit financing and money laundering

- drugs

- modern slavery and human trafficking

- intellectual property crime.

There is a separate section in the control strategy covering fraud, highlighting the main issues. Specialist teams such as the dedicated card and payment crime unit have been developed to tackle specific threats.

Resources and skills

The CoLP should make sure it has sufficient intelligence staff to effectively analyse the threats it faces

We found that resourcing issues were hampering the force’s approach to SOC in several areas:

- A theme common to this inspection and the force’s last PEEL inspection is the lack of available analysts.

- The intelligence department aims to provide around-the-clock support but is only able to provide cover until 10pm.

- The sensitive intelligence unit is operating with one supervisor and one analyst. This limits its effectiveness and provides little resilience.

- The force has one member of staff in the ROCTA. Their effectiveness is limited by having no access to intelligence in other regional forces. There is no backup to cover this role.

As the national lead for fraud, the CoLP hosts some specialist resources

The force hosts some specialist anti-fraud resources. These include the following:

- The insurance fraud enforcement department is a unit funded entirely by the insurance industry to combat fraud.

- The police intellectual property crime unit is the country’s only dedicated intellectual property crime unit, funded by a direct grant from the intellectual property office.

- The dedicated card and payment crime unit is a team run jointly by the CoLP and the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS). It is funded by the banking industry, with the sole purpose of combating crimes associated with banking payments.

Additionally, the CoLP hosts the national fraud and cybercrime reporting centre. This is critical to supporting the approach to these two crime types. The force also co-ordinates regional fraud resources based in the nine ROCUs across England and Wales, through the funding it receives from the Home Office.

Tackling SOC and safeguarding people and communities

The CoLP is effective at conducting investigations

We saw examples of effective investigations that had achieved significant results. These included:

- a money laundering investigation that identified a professional enabler and a subsequent account forfeiture order for €34m; and

- the disruption of a drug trafficking crime group that was using hotels and Airbnb accommodation to supply controlled drugs.

The CoLP works with partners to share information and protect communities from fraud

The CoLP, through its role as national lead force for fraud, is responsible for routinely sharing information locally and nationally to protect communities from SOC. This is done alongside the various partners from the financial sector.

One example is its work alongside UK Finance. The CoLP works with a dedicated prevent team that presents webinars to share key messages with the business community to prevent people becoming victims of crime.

The CoLP manages the National Fraud Intelligence Bureau and Action Fraud. These communicate alerts when new threats are identified, to protect the public and business community against new and emerging threats.

The CoLP has personnel dedicated to preventing people from becoming victims of fraud

We saw several diversionary schemes run by the CoLP, consistent with its role as national lead force for fraud. These focused on fraud and the impacts on the local business community. Examples included the following:

- The national economic crime victim unit is part of the National Fraud Intelligence Bureau. The unit focuses on preventing the public from becoming repeat victims.

- The cyber unit has prevent and disrupt personnel dedicated to taking down websites suspected of perpetrating fraud.

- The Insurance Fraud Bureau has dedicated personnel working alongside the insurance industry to develop strategies to prevent insurance fraud.

- The force has developed a project to prevent romance and courier fraud across the UK. It has conducted evidence-based research into these crime types to understand the demographics of the victims. It has then deployed preventative messaging.

The CoLP is working to tackle crime connected with the nighttime economy

Following the pandemic, the force identified a change in the nighttime economy. More staff were working from home and consequently not travelling into the City.

The force has recognised this as an opportunity to tackle crime in the nighttime economy, including those engaged in drug supply. Although in its early stages, this may provide opportunities to understand and disrupt OCGs operating in the City. The force has established Operation Reframe to work with partners, such as the London Fire Brigade, and concentrate on keeping people safe in the City.

In addition, the City of London Corporation, of which the CoLP is part, received funding from the Home Office to introduce a campaign to help prevent violence against women and girls. The force has started to roll out the campaign by training staff in bars and other venues.

Read An inspection of the London regional response to serious and organised crime – May 2023

Requires improvement

Building, supporting and protecting the workforce

The City of London Police is adequate at building and developing its workforce.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force builds and develops its workforce.

Frontline staff feel disconnected from senior leaders. They found ranks above chief inspector weren’t visible, supportive, and mainly inaccessible

We found that most frontline staff felt they were provided no support, guidance, or leadership from ranks above chief inspector. We found teams that weren’t aware of which superintendent had responsibility for them, and they rarely saw anyone of that rank or above. Staff reported the only time they heard from senior leaders was to gain updates on investigations, outside the set protocols. Most found this overly intrusive and unnecessary. It was mainly done to service the senior officer’s need for information and wasn’t seen as supportive. Most stated that the visibility of senior ranks was poor. However, most staff we spoke to had noticed the change in focus introduced by the new chief officer team as part of the force’s objectives: to focus on victims and people. This was mainly being led by their immediate line managers. To ensure full cultural change, there needs to be real and focused leadership from all ranks. This disconnection needs to be addressed urgently to provide staff with clear and visible senior leadership.

The force’s efforts to support staff well-being are being undermined by high workloads and vacancies across the force

Well-being is a priority, highlighted by the commissioner in her new strategy for the force. Staff generally feel supported by their managers and feel that managers genuinely care about their welfare. The force has an extensive occupational health service provided for them by the City of London Corporation. Staff were positive about the service if they had used it but found it hard to access via the intranet or through a referral. There are also local arrangements in place for informal well-being support. These include a well-being room at Bishopsgate, and the provision of taxis and hotel accommodation if staff are struggling to get home when retained on duty.

But we found that many frontline policing staff felt too busy to use the available occupational health or informal well-being services. Some told us that they didn’t tell their supervisors about how they felt at work, because their supervisors couldn’t reduce the pressure. This was mainly down to vacancies in certain departments.

The well-being board is responsible for the oversight and governance of well-being. And there is a strategic lead at chief superintendent rank. This board was introduced with the new strategic governance framework, so it wasn’t possible to assess the effect of its oversight. This is an area the force needs to maintain focus on and improve staff access to support facilities.

The force has realistic recruitment plans and has made good progress in the transition to policing education qualifications framework. They are also taking effective action so that its workforce better reflects its communities

The force has dedicated staff to the PUP, and while its plans are ambitious, they are being achieved. It has plans to recruit up to 24 detectives via Police Now and the student pathway during 2023. The programme has a weekly governance meeting at superintendent level.

It also has a clear plan to recruit a workforce that better reflects the community. Its inclusion and diversity strategy sets out projects which should help to achieve greater diversity. The recruitment strategy has been targeting specific communities to maximise opportunities to increase broader representation. The force is working with Police Now (for female candidates) and targeting university recruitment fairs (for graduates). As of 31 March 2022, 23 percent of the force’s police officers were female; the lowest proportion of any force in England and Wales. The ambition is to increase this proportion to 50 percent. This would align more closely with the 58 percent of police staff that are female. Given the ambitious targets that have been set, the force needs to reassure itself that enough people with the right skills in HR and learning and development to continue with these programmes after the PUP funding ceases.

The force makes good use of volunteers to increase resilience, fairness, and diversity in the workplace

The force has a well-developed cadet programme that is co-ordinated from the sector team within the Partnership and Prevention hub. Together with the Amazon project and the development of a youth IASG, this gives the force a valuable perspective from young people, a group policing often finds it hard to engage with effectively. They plan to further develop this youth outreach with a dedicated schools co-ordinator in 2023.

The force has a valued and diverse IASG which is represented at force governance meetings and on the ethics boards. It reviews intrusive tactics to show fairness and proportionality. The force has recently used IASG members on promotion interviews to provide transparency and fairness. This is an excellent use of volunteers to provide much needed diversity.

Adequate

Strategic planning, organisational management and value for money

The City of London Police requires improvement at operating efficiently.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force operates efficiently.

The force has a clear governance framework, but should ensure it is underpinned with high-quality data, allowing more appropriate challenge and direction

The City of London Police has a governance framework which ensures it focuses on its priorities. The force has regular ‘day of meetings’, which helps senior officers plan their calendar and ensure attendance. This allows them to disseminate the decisions from the day of meetings to regular tasking groups.

We observed some of these meetings. While they were well attended, the force should ensure it is maximising its use of the data and technology it has. The force should ensure it is using Power BI, so decision makers are using the most up-to-date data, to minimise the impact on its scarce analytical resource and maximise the attendance and availability of the most senior people in the organisation. This will allow senior leaders to provide better challenge and direction in these key meetings.

The force has a balanced medium term financial plan

The force presents a balanced medium term financial plan and is confident that it can achieve the savings and investment needed.

To balance the budget the force needs to make cumulative savings of £13.8m, including an expected increase in Business Rate Premium, appropriate use of Proceeds of Crime Act reserves and some one-off savings. However, to achieve these savings the force will need to make sustained savings of £1m linked to the corporate services review.

Priorities for the force capital fund include fleet replacement.

The force should assure itself that it is providing value for money

The force has access to a wide range of equipment both within the force and because of funding from the City of London Corporation. Officers have access to tablets and laptops which work seamlessly with wi-fi in London. The force has access to a comprehensive CCTV system in place across the city. There is a large fleet in the City of London Police, despite the small geographic area the force covers, and the force has recently begun using Power BI.

But we found the force wasn’t assessing the benefit of this technology and equipment which means it can’t assure itself that the technology is providing value for money, nor can the force easily identify where it can improve or refine this technology. The force needs to ensure it is realising the benefits of the investments it makes, and that it has the supporting resource funded and in place to ensure it fully uses the technology it invests in.

The force should ensure it has benefits analysis in place to check that investments produce the benefits the force expects.

Requires improvement

About the data

Data in this report is from a range of sources, including:

- Home Office;

- Office for National Statistics (ONS);

- our inspection fieldwork; and

- data we collected directly from all 43 police forces in England and Wales.

When we collected data directly from police forces, we took reasonable steps to agree the design of the data collection with forces and with other interested parties such as the Home Office. We gave forces several opportunities to quality assure and validate the data they gave us, to make sure it was accurate. We shared the submitted data with forces, so they could review their own and other forces’ data. This allowed them to analyse where data was notably different from other forces or internally inconsistent.

We set out the source of this report’s data below.

Methodology

Data in the report

British Transport Police was outside the scope of inspection. Any aggregated totals for England and Wales exclude British Transport Police data, so will differ from those published by the Home Office.

When other forces were unable to supply data, we mention this under the relevant sections below.

Outlier Lines

The dotted lines on the Bar Charts show one Standard Deviation (sd) above and below the unweighted mean across all forces. Where the distribution of the scores appears normally distributed, the sd is calculated in the normal way. If the forces are not normally distributed, the scores are transformed by taking logs and a Shapiro Wilks test performed to see if this creates a more normal distribution. If it does, the logged values are used to estimate the sd. If not, the sd is calculated using the normal values. Forces with scores more than 1 sd units from the mean (i.e. with Z-scores greater than 1, or less than -1) are considered as showing performance well above, or well below, average. These forces will be outside the dotted lines on the Bar Chart. Typically, 32% of forces will be above or below these lines for any given measure.

Population

For all uses of population as a denominator in our calculations, unless otherwise noted, we use ONS mid-2020 population estimates.

Survey of police workforce

We surveyed the police workforce across England and Wales, to understand their views on workloads, redeployment and how suitable their assigned tasks were. This survey was a non-statistical, voluntary sample so the results may not be representative of the workforce population. The number of responses per force varied. So we treated results with caution and didn’t use them to assess individual force performance. Instead, we identified themes that we could explore further during fieldwork.

Victim Service Assessment

Our victim service assessments (VSAs) will track a victim’s journey from reporting a crime to the police, through to outcome stage. All forces will be subjected to a VSA within our PEEL inspection programme. Some forces will be selected to additionally be tested on crime recording, in a way that ensures every force is assessed on its crime recording practices at least every three years.

Details of the technical methodology for the Victim Service Assessment.

Data sources

Domestic abuse outcomes

Domestic abuse outcome proportions show the percentage of crimes recorded in the 12 months ending 31 March 2021 that have been assigned each outcome. 28 police forces provided domestic abuse outcomes data through the Home Office data hub (HODH) every month. We collected this data directly from 14 forces, with Greater Manchester Police unable to provide data for all time periods in the year. This means that each crime is tracked or linked to its outcome. This data is subject to change, as more crimes are assigned outcomes over time.