Overall summary

Our inspection assessed how good Avon and Somerset Constabulary is in ten areas of policing. We make graded judgments in nine of these ten as follows:

We also inspected how effective a service Avon and Somerset Constabulary gives to victims of crime. We don’t make a graded judgment in this overall area.

We set out our detailed findings about things the force is doing well and where the force should improve in the rest of this report.

Important changes to PEEL

In 2014, we introduced our police effectiveness, efficiency and legitimacy (PEEL) inspections, which assess the performance of all 43 police forces in England and Wales. Since then, we have been continuously adapting our approach and during the past year we have seen the most significant changes yet.

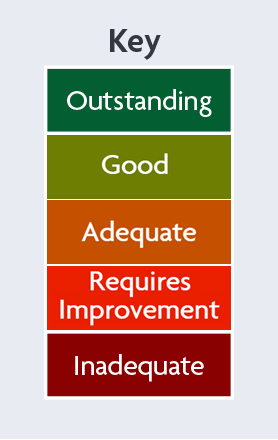

We now use a more intelligence-led, continual assessment approach, rather than the annual PEEL inspections we used in previous years. For instance, we have integrated our rolling crime data integrity inspections into these PEEL assessments. Our PEEL victim service assessment also includes a crime data integrity element in at least every other assessment. We have also changed our approach to graded judgments. We now assess forces against the characteristics of good performance, set out in the PEEL Assessment Framework 2021/22, and we more clearly link our judgments to causes of concern and areas for improvement. We have also expanded our previous four-tier system of judgments to five tiers. As a result, we can state more precisely where we consider improvement is needed and highlight more effectively the best ways of doing things.

However, these changes mean that it isn’t possible to make direct comparisons between the grades awarded in this round of PEEL inspections with those from previous years. A reduction in grade, particularly from good to adequate, doesn’t necessarily mean that there has been a reduction in performance, unless we say so in the report.

HM Inspector’s observations

I am satisfied with some aspects of the performance of Avon and Somerset Constabulary in keeping people safe and reducing crime, but there are areas where the constabulary needs to improve.

These are the findings I consider most important from our assessments of the constabulary over the last year.

The constabulary is outstanding in the way it engages with and treats the public

The constabulary has a clear strategy for engaging with the communities it protects. It uses innovative methods, including partnering with local creative businesses, to engage with the public. We saw good examples of the constabulary responding to concerns raised through getting local communities involved, such as the establishment of an internal group to review the constabulary’s arrangements for interacting with users of British Sign Language (BSL).

The constabulary answers emergency and non-emergency calls quickly but repeat and vulnerable victims aren’t always identified, and it doesn’t always attend calls for service promptly

The constabulary answers emergency and non-emergency calls within national timescales, but when calls are answered, the victim’s vulnerability isn’t always assessed using a structured process. This could affect the understanding of the victim’s specific needs, and how quickly the constabulary should respond. And it doesn’t always attend the associated incident within the timescale it has set, based on the priority of the call. It should make efforts to ensure the call priority is changed if appropriate after the original call is taken and should take into account any additional information relating to risk and victim vulnerability.

The constabulary should make improvements to the way it records crime

During the 1-year period under inspection, the constabulary recorded 91.4 percent of all reported crime (excluding fraud), which leads to an estimate that more than 13,100 crimes weren’t recorded during this period. These include violent and sexual offences. The constabulary should therefore ensure that systems and processes are in place to accurately record crime to ensure that victims get the level of service they require.

My report sets out the fuller findings of this inspection. I will monitor the constabulary’s progress where areas for improvement have been identified.

Wendy Williams

HM Inspector of Constabulary

Providing a service to the victims of crime

Victim service assessment

This section describes our assessment of the service Avon and Somerset Constabulary provides to victims. This is from the point of reporting a crime and throughout the investigation. As part of this assessment, we reviewed 90 case files.

When the police close a case of a reported crime, it is assigned an ‘outcome type’. This describes the reason for closing it. We also reviewed 20 cases for each of the following outcome types:

- A suspect was identified and the victim supported police action, but evidential difficulties prevented further action (outcome 15).

- A suspect was identified, but there were evidential difficulties and the victim didn’t support, or withdrew their support for, police action (outcome 16).

- The police decided that further investigation against a named suspect wasn’t in the public interest (outcome 21).

While this assessment is ungraded, it influences graded judgments in the other areas we have inspected.

The constabulary answers emergency and non-emergency calls quickly but repeat and vulnerable victims aren’t always identified

When a victim contacts the police, it is important that their call is answered quickly and that the right information is recorded accurately on police systems. The caller should be spoken to in a professional manner. The information should be assessed, taking into consideration threat, harm, risk and vulnerability. The victim should also receive appropriate safeguarding advice.

The constabulary answers emergency and non-emergency calls promptly, meeting national standards for call handling and recording the highest levels nationally. Call handlers give victims advice on crime prevention and preservation of evidence most of the time. However, when calls are answered, the victim’s vulnerability isn’t always assessed using a structured process. Repeat victims aren’t always identified, which means this information isn’t taken into account when considering the response the victim should receive.

The constabulary doesn’t always respond promptly to calls for service

A constabulary should aim to respond to calls for service within its published time frames, based on the prioritisation given to the call. It should change call priority only if the original prioritisation is deemed inappropriate, or if further information suggests a change is needed. The constabulary’s response should take into consideration risk and victim vulnerability, including any information obtained after the call.

On most occasions, the constabulary responds to calls by sending appropriately trained staff. But it doesn’t always respond within its own published time frames. Victims aren’t always informed of delays and therefore their expectations aren’t always met. This may cause victims to lose confidence and disengage from the process.

The constabulary’s crime recording requires improvement to ensure victims receive an appropriate level of service

The constabulary’s crime recording should be trustworthy. The constabulary should be effective at recording reported crime in line with national standards and have effective systems and processes, supported by its leadership and culture.

The constabulary needs to improve its crime recording processes to make sure that all crimes reported to it are recorded correctly and without delay.

We set out more details about the constabulary’s crime recording in the ‘crime data integrity’ section below.

The constabulary makes sure that investigations are allocated to staff with suitable levels of experience

Police forces should have a policy to make sure crimes are allocated to suitably trained officers or staff for investigation or, if appropriate, not investigated further. The policy should be applied consistently. The victim of the crime should be kept informed of the allocation and whether the crime is to be further investigated.

We found the constabulary allocates recorded crimes for investigation according to its policy. In nearly all cases, the crime is allocated to the most appropriate department for further investigation.

The constabulary usually carries out effective and timely investigations, which are well supervised

Police forces should investigate reported crimes quickly, proportionately and thoroughly. Victims should be kept updated about the investigation and the force should have effective governance arrangements to make sure investigation standards are high.

In most cases, the constabulary carries out investigations in a timely way and completes relevant and proportionate lines of inquiry. Investigations are well supervised. However, appropriate investigation plans aren’t always put in place. Victims are usually updated throughout. Victims are more likely to have confidence in a police investigation when they receive regular updates.

When victims withdraw support for an investigation, the constabulary doesn’t always consider progressing the case without the victim’s support. This can be an important method of safeguarding the victim and preventing further offences from being committed. The constabulary doesn’t always record whether it considers using notices or orders designed to protect victims, such as domestic violence protection notices or domestic violence protection orders.

The Code of Practice for Victims of Crime requires police forces to carry out a needs assessment at an early stage to determine whether victims need additional support. The constabulary doesn’t always carry out this assessment or record the request for additional support.

The constabulary doesn’t always use the right outcome, consider victims’ wishes or hold an auditable record of victims’ wishes

The constabulary should make sure it follows national guidance and rules for deciding the outcome of each report of crime. In deciding the outcome, the constabulary should consider the nature of the crime, the offender and the victim. And the constabulary should show the necessary leadership and culture to make sure the use of outcomes is appropriate.

When a suspect has been identified and the victim supports police action, but evidential difficulties prevent further action, the victim should be informed of the decision to close the investigation. The constabulary usually uses this outcome correctly.

When a suspect has been identified but the victim doesn’t support or withdraws their support for police action, an auditable record from the victim should be held confirming their decision. This allows the investigation to be closed. In half the cases we reviewed, an auditable record of the victim’s wishes was absent. This represents a risk that the victim’s wishes may not be fully represented and considered before the investigation is closed.

When a suspect has been identified and the police decide that further investigation isn’t in the public interest, the victim should be consulted and informed of the decision. However, not all victims are informed of the decision to take no further investigative action and, on some occasions, victims’ views aren’t considered. On occasions, the outcome isn’t used appropriately.

Crime data integrity

Avon and Somerset Constabulary requires improvement at recording crime.

We estimate that Avon and Somerset Constabulary is recording 91.4 percent (with a confidence interval of +/- 2.6 percent) of all reported crime (excluding fraud). We estimate this means the constabulary didn’t record more than 13,100 crimes during the year covered by our inspection.

We estimate that the constabulary is recording 86.6 percent (with a confidence interval of +/- 4.6 percent) of violent offences. We estimate this means the constabulary didn’t record more than 8,300 violent offences during the year covered by our inspection.

We estimate that the constabulary is recording 92.9 percent (with a confidence interval of +/- 4.5 percent) of sexual offences. We estimate this means the constabulary didn’t record more than 420 sexual offences during the year covered by our inspection.

Main findings

In this section, we set out our main findings that relate to how well the constabulary records crime.

When the constabulary records crime it does so quickly and efficiently

The constabulary has systems and processes in place to ensure crimes are recorded quickly. Timely and efficient recording of crime ensures victims can access support services quickly and investigations aren’t held up.

Recording data about crime

Avon and Somerset Constabulary requires improvement at recording crime.

Accurate crime recording is vital to providing a good service to the victims of crime. We inspected crime recording in Avon and Somerset as part of our victim service assessments (VSAs). These track a victim’s journey from reporting a crime to the police, through to the outcome.

All forces are subject to a VSA within our PEEL inspection programme. In every other inspection forces will be assessed on their crime recording and given a separate grade.

You can see what we found in the ‘Providing a service to victims of crime’ section of this report.

Requires improvement

Engaging with and treating the public with fairness and respect

Avon and Somerset Constabulary is outstanding at treating people fairly and with respect.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to treating people fairly and with respect.

The constabulary has a clear strategy for working with diverse communities and responds effectively to concerns raised

The constabulary has a recently updated strategy for working with communities in its area. Each local policing area has a specific delivery plan which outlines how the local policing team will engage with its community. And the constabulary measures the success of this engagement through a variety of channels, including a quarterly delivery group and a weekly directorate meeting, chaired by a senior officer.

We saw good examples of the constabulary responding to concerns raised through getting local communities involved. For example, the constabulary attended an event for BSL and received feedback from the community that BSL isn’t always recognised and understood, so that those who are hard of hearing and using BSL are unable to communicate their concerns effectively. The constabulary has responded to this feedback by setting up a task and finish group to review arrangements so the constabulary can interact with the BSL community in a more positive way.

The constabulary also responds effectively to concerns raised through social media. It uses a management tool covering over 70 social media accounts, which monitors the public’s responses to its posts so the constabulary can provide a response and apply safeguarding where appropriate.

And the process is not just one way. The constabulary’s outreach team proactively engages with communities. For example, it uses radio stations – whose audiences primarily represent minority groups – as a platform for phone-in sessions to seek their views and understand what is important to them.

The constabulary offers the public a wide range of ways to get involved in its work. It has seen a positive uptake in its ‘Citizens in Policing’ initiative. This includes police support volunteers, police cadets and community watch schemes. In addition, independent advisory groups (IAGs) and strategic IAGs are active and have a range of members of different communities.

The constabulary is also focusing on a women’s IAG and a youth IAG to improve engagement with representatives from those groups.

Officers are trained to consider fairness and equality during encounters with the public, and receive cultural awareness training

Perceptions of unfair behaviour by police officers can damage public confidence. The constabulary has developed a ‘Taking the Hurt out of Hate’ training programme for its workforce. This offers a range of training opportunities to address unfair behaviour, communication, stereotyping, identification and management of hate crime, and listening to and acting on community feedback.

The constabulary has recently piloted the College of Policing’s scenario-based officer safety training. This is designed to encourage officers to think about the circumstances they face and to consider their actions, including communication skills and level of force needed. It also includes a feature on stop and search training.

Conflict resolution and cultural awareness training is included as part of the training courses in the constabulary. This is reinforced by senior leaders, who have attended ‘Cultural Intelligence for Inclusive Leaders’ training and who encourage officers to understand diversity and protected characteristics, to support them with their interactions with the public. The constabulary aims to promote the development of equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) through inclusive leadership to strengthen its engagement with communities in a more informed way.

The constabulary has effective internal scrutiny of stop and search and use of force, including peer review

The constabulary monitors stop and search and use of force via an internal panel that meets regularly to discuss performance data on the use of these powers. We observed these panel meetings and found they were effective, involving active discussions and the sharing of good practice across the constabulary. We saw productive discussions related to developing technology to make it easier for officers to complete stop and search records on mobile phones. And we noted the development of training materials involving practical, scenario-based advice for officers.

Internal scrutiny of stop and search has also supported the development of a stop and search delivery plan. In addition, the constabulary has a use-of-force audit group and an internal working group, consisting of officers and staff, for assessing disproportionality in stop and search. Disproportionality in this context refers to certain groups of people being affected by the use of police powers in a substantially different way from people in another group. For example, officers may be conducting stop and search more often with people of a particular gender, age or ethnicity.

Officers and supervisors dip-sample (review a random selection of) encounters where use of force occurs or stop and search powers are used. This includes assessing body-worn video footage to identify learning opportunities and keep standards high. In addition, senior officers review audits to determine any themes that require additional scrutiny to help drive improvements. Frontline supervisors are equipped with the relevant data using Qlik Sense to assess use of force performance at a team and individual level. Qlik Sense is an online application that allows users to create visualisations of data to assist analysis and understanding. (The constabulary pioneered the use of this tool, and it is now used by several other forces across the UK.) The tool can be used to, for example, track the number of times force is used over a specified period, as well as tactics used and geographical areas.

The constabulary and the office of the police and crime commissioner (OPCC) led an event following an independent review that examined the local response to the David Lammy report, The Lammy Review, concerning racial disparity. The constabulary openly shared data and information concerning disparity that they identified in:

The stop and search delivery plan is separated into key themes and incorporates formal recommendations from internal governance structures and external stakeholders. It also includes feedback following working with communities and officers to ensure the constabulary is using stop and search powers confidently and legitimately. The themes include:

- disproportionality;

- scrutiny;

- engagement and communications;

- children and young people;

- training;

- governance and policy; and

- performance and processes.

The constabulary has effective external scrutiny of stop and search and use of force

The constabulary has effective and independent scrutiny of the use of force, and stop and search, by its officers. The OPCC chairs an external scrutiny panel. The constabulary provides this panel with information and comprehensive data in advance of each meeting.

Panel members, made up of local representatives from a variety of communities, view body-worn video footage of randomly selected incidents before splitting into smaller groups to consider and report concerns. We found that panel members offered appropriate challenge on cases reviewed and thorough review of the circumstances of each case.

We found that learning was shared with relevant officers and supervisors. Chief officers are in attendance to reinforce the importance of the meetings and address any resulting concerns. The meetings include a ‘you said, we did’ section to provide feedback on issues raised and offer specific responses to previously discussed cases.

Minutes of meetings, including recommendations, are published on the OPCC website and panel members share their considerations with the communities they represent.

There is also the independent scrutiny of police powers panel, which is made up of local people from a diverse range of backgrounds. Panel members attend quarterly meetings to review a sample of files and footage on the use of police powers. This includes the use of handcuffing in stop and search. Results are fed back to the PCC and the police to help drive improvements, such as introducing new training on the use of tasers on individuals who have mental health problems.

The constabulary considers disproportionality in stop and search, but is still developing an approach to understand it

We found that the constabulary is currently developing its understanding of disproportionality in the area of stop and search. Disproportionality is examined in internal and external scrutiny panels, and the constabulary has seen the levels of disproportionality reduce over time.

The constabulary is taking steps to better understand this issue, taking into account the recommendations of The Lammy Review, and a 2022 report into disproportionality in the Avon and Somerset criminal justice system. It is also analysing the reasons behind stop and searches and has developed an IT solution to ensure that a stop and search record can’t be submitted unless the ethnicity of the person stopped is properly recorded.

The constabulary’s commendable focus on improving training and the establishment of a more diverse workforce may be contributing factors in the reduction in disproportionality the constabulary has seen from its internal monitoring. But it should ensure it has the right information, and the right analysis of that information, to understand the factors that affect disproportionality.

The constabulary doesn’t always record the grounds for stop and search encounters effectively

During our inspection, we reviewed a sample of 182 stop and search records from 1 January to 31 December 2021. Based on this sample, we estimate that 87.4 percent (with a confidence interval of +/- 4.8 percent) of all stop and searches by the constabulary during this period had reasonable grounds recorded. This is broadly unchanged compared with the findings from our previous review of records from 2019, where we found 86.5 percent (with a confidence interval of +/- 4.3 percent) of stop and searches had reasonable grounds recorded. Of the records we reviewed for stop and searches on people from ethnic minority backgrounds, 21 of 24 had reasonable grounds recorded.

The audit measures the quality of the grounds only as they are recorded on the stop and search form, not whether the grounds themselves were reasonable at the time of the encounter. Where grounds aren’t recorded or are merely recorded with insufficient or incorrect detail, the constabulary should make sure it understands whether officers are searching without reasonable grounds.

Outstanding

Preventing crime and anti-social behaviour

Avon and Somerset Constabulary is adequate at prevention and deterrence.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to prevention and deterrence.

The constabulary problem-solves well with partner organisations to protect the vulnerable and reduce demand

We found the constabulary works effectively with a wide partnership of agencies to protect the vulnerable and reduce demand. One of many good examples of this involved the constabulary working with the local authority, health service, fire and rescue service and a dementia charity. This group set about safeguarding a group of people with dementia. Financial support was obtained from the private sector to purchase tracking equipment. This helped relatives of those with dementia, and others who may find them, to return them to safety without any police intervention. This initiative almost completely diverted demand away from police officers but more importantly protected some of the most vulnerable from harm.

However, the constabulary’s overall approach to problem-solving is not always as effective. The constabulary recently audited 102 of its problem-solving plans and by its own assessment found that, while 49 were of sufficient quality, 53 needed to improve. These findings have led to the creation of an improvement plan which aims to provide improvements in training, the implementation of performance reviews and the creation of forums where officers and staff can seek guidance from specialist staff.

The constabulary also has a two-monthly problem-solving plan working group, which meets to discuss improvements to the whole process.

The constabulary effectively identifies high demand and vulnerability, and then prioritises work on reducing it

The constabulary uses IT systems to support neighbourhood policing officers in the identification of locations, individuals and groups of people that cause high levels of demand or are particularly vulnerable to victimisation. Performance meetings focus on these locations and people to help staff prevent offences.

A daily one team tasking meeting is held to discuss demand, risk, threat, harm, vulnerability and resources, providing leadership and clarity. In this way demand for neighbourhood policing is well understood and resources are used appropriately, balanced against more immediate calls for service. Performance meetings focus on these locations and people to help staff prevent offences. The meeting we observed clearly identified threat, harm and risk in communities, and ensured there was clarity over who would be tasked to deal with reducing or preventing it. This reduction or prevention included targeted early intervention work and identifying and patrolling hotspots.

A good example of this that we saw was a problem-solving plan used to collate information relating to drink-spiking incidents, focusing on vulnerability and repeat locations.

The constabulary has invested in early intervention approaches to prevent crime and disorder

The constabulary has eight locally based early intervention (EI) teams, linked to neighbourhood policing teams but with separate governance. The leaders of these teams meet regularly and discuss matters such as violence, gang-related crime and ASB. Issues are brought up at an early stage with the aim of intervening early to prevent crime. The teams use police data provided by Qlik Sense to help predict problems at an early stage (for example, a child who may be vulnerable but falling below a high-risk threshold).

Cases are also discussed at productive and regular meetings with public sector partner organisations, where EI teams can access additional partnership information (such as from health services) to better and more quickly understand problems. For example, when a child is identified as being at a heightened risk of becoming an offender or a victim of crime, a multi-agency case conference takes place to formulate a joint action plan to mobilise partner resources to prioritise the protection of the child and the prevention of crime and disorder.

Members of the EI teams have also received specialist training to help them interview children more effectively. The constabulary has committed to developing this trauma‑informed approach with further training planned in the medium term.

In addition, the constabulary is taking a preventative approach to other serious issues such as child sexual exploitation and county lines drug dealing. Specialist officers regularly provide input to schools in relation to the signs and dangers of these practices.

The constabulary doesn’t fully understand the impact on its officers and staff and their workloads when neighbourhood policing officers are taken away from their normal roles to focus on additional demands

Neighbourhood policing officers are responsible for problem-solving and getting local communities involved. These duties often require a sustained, longer-term approach than response policing. If neighbourhood policing officers are regularly diverted from these duties this can dilute the impact of this work. Officers being diverted from their duties, whether to support response teams or undertake specialist roles elsewhere, is often referred to as ‘abstraction’.

The constabulary monitors its demand and officer and staff abstractions using software that all teams can access. The daily levels of demand are overseen and managed at the daily one team tasking meeting. Where possible, neighbourhood policing teams focusing on problem-solving are disrupted only when necessary.

To cater for longer-term changes in demand, for example over the busy summer months, the constabulary uses analytical software to predict the number of officers they will need to better respond to the public’s needs. Under the name of Operation Hibiscus, neighbourhood policing officers are then added to response teams to deal with priority calls from the public and are to an extent taken away from their preventative roles.

We found that neighbourhood policing teams are adversely affected by the abstraction of their officers and staff during this busy period, which is arguably when more long-term problems arise that require solving. Although this happens only when necessary, constables are sometimes abstracted from their teams for weeks at a time, resulting in increased workloads for their sergeants, the remaining constables and police community support officers.

Therefore, the ability of neighbourhood policing teams to reduce the demand they deal with is reduced, as is their level of service to the public, including victims of crime. Officers and staff told us they found Operation Hibiscus very disruptive when they were re-deployed and that it made them feel that the constabulary didn’t appreciate the work they did in their normal role.

The constabulary has recognised this and is piloting a programme to improve its monitoring of the demand and impact on neighbourhood policing teams.

Adequate

Responding to the public

Avon and Somerset Constabulary requires improvement at responding to the public.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the constabulary responds to the public.

The constabulary understands the need to assess vulnerability at the first point of contact with callers but doesn’t always do so to the required standard

When calls are answered in the communication centre, we found that call handlers were polite and professional, and showed empathy to callers. The initial prioritisation, response and supervision of calls for service was appropriate in most cases. But in 14 of 65 cases we reviewed, the victim’s vulnerability wasn’t assessed using a structured risk assessment (THRIVE). This should be done from the outset to make sure that any risk, threat or vulnerability relating to the caller is identified.

We also found that, in cases where a THRIVE assessment was conducted, there was no consistent format, meaning they were often variable in form or quality. And they were often difficult to locate on call logs. This makes it more difficult for the constabulary to determine risk as well as opportunities for early investigation and preservation of evidence.

The constabulary has already introduced a new structured assessment template for call handlers to use to improve recording and assessments. The constabulary should ensure that call handlers are using this to better inform the prioritisation given to the call and the most appropriate response. The constabulary should also ensure that all the relevant information is gathered and passed to responding officers.

The constabulary has a good understanding of the demand it faces through the effective use of IT analytical tools

We found that the constabulary had an effective management process capable of prioritising demand with available resources.

The constabulary monitors how many 999 or 101 calls are waiting to be answered, as well as the longest waiting time, via a dashboard which is visible on large screens to all staff working in the communication centre. This helps everyone to respond to calls quickly.

In May 2022, the Home Office started to publish data on 999 call answering times. Call answering time is the time taken for a call to be transferred from British Telecom to a force, plus the time taken by that force to answer it. In England and Wales, forces should aim to answer 90 percent of these calls within 10 seconds. We have used this data to assess how quickly forces answer 999 calls. We do acknowledge, however, that this data has been published only recently. As such, we recognise that forces may need time to consider any differences between the data published by the Home Office and their own.

Between 1 November 2021 and 31 July 2022 Avon and Somerset Constabulary answered 89.4 percent of 999 calls within 10 seconds. Although this was slightly below the standard of 90 percent, it was the highest proportion across all forces in England and Wales, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Proportion of 999 calls answered within 10 seconds, by constabulary in England and Wales, between 1 November 2021 and 31 July 2022

The constabulary uses IT systems to manage current demand and to predict likely future demand. We found good examples of resources being re-deployed to meet predicted demand. Operation Hibiscus effectively identified longer-term demand, even though we did encounter dissatisfaction with how its solutions were implemented.

First responders receive accreditation, training and continuing professional development

Supervisors in the communication centre are subject to an accreditation process, and response officers receive 2 training days every 11 weeks built into their shift pattern. Response officer driver training has increased to cover a shortage, and all officers have recently had Domestic Abuse Matters training from SafeLives and vulnerability training.

Officers are also due to have additional training in how to complete safeguarding assessments. The detainee investigation team, which deals with people arrested by the response teams, also provides individual and general feedback on their own performance. We found that feedback wasn’t always positive and did helpfully establish areas that could be improved.

Requires improvement

Investigating crime

Avon and Somerset Constabulary requires improvement at investigating crime.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the constabulary investigates crime.

The constabulary has a shortage of qualified detectives and police staff investigators

As of 31 March 2022, the constabulary had filled only 56 percent of its 532 professionalising investigations programme (PIP 2) investigator posts with accredited investigators. This meant there was a shortfall of 232 accredited investigators. At that time, 125 trainees were also in place to fill this gap, although this placed a burden on tutors who had responsibility for their day-to-day training. And the constabulary doesn’t have enough tutors to mentor trainee investigators, with up to four trainees being supported by a single mentor in some cases.

Although the constabulary is taking steps to increase the number of investigators, it may take some time for those investigators to be fully trained and to achieve accreditation. As a result, the quality and timeliness of investigations may suffer, as well as how promptly they are allocated. This could affect the quality of service to victims of serious crime.

The constabulary has recognised this as a problem and has set up the Investigations Transformation Project with the aim of recruiting 107 additional investigators, focusing on areas such as leadership, attraction and retention. However, it is acknowledged that full capacity might not be reached until 2025 when the full effect of recruitment via the Police Uplift Programme is realised.

The constabulary is also using several ways to increase the number of detectives in the organisation. These include the Detective Degree Holder Entry Programme, the recruitment of officers from other areas of the constabulary, attracting recruits via the Police Now National Detective Programme, recruiting police staff investigators and providing opportunities for existing police staff investigators to become detective constables.

Too many investigations result in no further action being taken

We found that in 89 of 90 cases we reviewed, victims received an appropriate service and that 78 of 90 investigations were effective. However, on occasions when the victim withdrew support for the investigation only 5 out of 12 investigations were actively pursued.

These figures suggest that opportunities to bring offenders to justice are potentially being missed. The figures could also help to explain why half of all investigations in the constabulary considered for prosecution lead to no further action being taken.

Nevertheless, we did find that the constabulary is addressing these issues. Opportunities to pursue investigations without the support of the victim are reviewed at daily management meetings. Learning on evidence-led prosecutions, including that provided by the College of Policing, is being rolled out across the constabulary. And the constabulary has a new investigation standards forum which provides oversight of the quality of investigations. In addition, the backlogs in the criminal justice system and general performance issues are regularly discussed at meetings with the Crown Prosecution Service and the courts.

The constabulary doesn’t always conduct victim needs assessments

The Code of Practice for Victims of Crime requires forces to carry out a needs assessment at an early stage to determine whether victims need additional support.

We found that the constabulary didn’t carry out this assessment or record the request for additional support in 9 of 49 cases we reviewed. Without such an assessment, the specific needs and wishes of the victim in terms of the investigation and its impact on them will not be known to the constabulary. And the constabulary may not provide the right kind of support to the victim throughout the investigation.

Effective governance is in place to manage the crime investigation process, and the constabulary understands its crime demand and allocates crimes appropriately

The constabulary’s chief officers have prioritised areas of crime investigation. They manage this through a series of meetings where senior officers are held accountable for performance. These meetings include the investigation directorate leadership meeting, which oversees priorities such as crime data integrity, investigation standards and timeliness, the investigation of rape and other serious sexual offences, and victim contact and satisfaction. This meeting in turn reports to the constabulary management board, where the constabulary’s overall performance and strategic issues are discussed.

The constabulary uses Qlik Sense to understand the demand on its crime investigation units. At the investigation directorate leadership meeting, consideration is given to demand and complexity over prolonged periods to better understand and manage changing trends as well as crime allocation and workload levels across the constabulary. This understanding has led to reviews, such as the constabulary refreshing its crime allocation policy to ensure that the right teams are investigating cases.

We found that 88 of 90 crime investigations we reviewed were allocated to appropriate teams within the constabulary. The constabulary uses a daily management meeting to ensure that this takes place. It currently allocates crime based firstly on the needs of the victim and secondly on the type of crime, so that the needs of the victim are always considered first.

Where areas for improvement have been identified via these governance processes, the constabulary has put measures in place to address them. Examples include plans concerning the number of unallocated investigations into rape and other serious sexual offences, the shortage of investigators and crime standards in general.

The constabulary manages the well-being of staff involved in investigations

The constabulary has a senior officer who is responsible for the overall well-being of its detectives and investigators, and a CID well-being team set up to achieve its objectives. This team takes advantage of the support available from the National Police Wellbeing Service and ensures that processes are in place such as the availability of psychological support and trauma risk management. Psychological screening is mandatory for some of the most traumatic roles (for example, the viewing of indecent images) and is discretionary for other investigation roles.

The investigators we spoke to told us they were well managed, and that their supervisors supported and looked after them in terms of their overall welfare. But the lack of qualified investigators and the number of unallocated crime investigations did influence their overall well-being.

Requires improvement

Protecting vulnerable people

Avon and Somerset Constabulary is adequate at protecting vulnerable people.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the constabulary protects vulnerable people.

The constabulary has effective leadership and governance of its efforts to tackle vulnerability and support victims

The constabulary has a mature approach to addressing vulnerability. This is exemplified by its adoption of the National Vulnerability Action Plan (NVAP) and the self-assessment it undertook to understand how the plan should be adopted in the constabulary.

The NVAP is a national model for addressing vulnerability in all its forms, identifying objectives across seven themes – including prevention, safeguarding and leadership – that forces should work towards in order to improve their response to vulnerability.

The constabulary completed a self-assessment to understand the gaps it had that might prevent it achieving the objectives in the NVAP. By doing this the constabulary was able to address these, and these efforts were recognised as good practice in a review by the Vulnerability Knowledge and Practice Programme.

The constabulary examines its progress against the NVAP at quarterly meetings. Its response to vulnerability is broken down into 15 strands, such as hate crime, mental health and child sexual exploitation, each of which has a thematic lead at chief inspector or superintendent rank, with oversight from the assistant chief constable. Furthermore, the constabulary has a confidence and legitimacy governance group chaired by the deputy chief constable, which considers risks and ensures resources are made available.

The constabulary is developing its surveying of victims to understand their experience in order to improve its services

The constabulary receives feedback on the victim experience via Lighthouse satisfaction surveys, which gather the experience of victims at the Lighthouse Safeguarding Units. It has also recently begun surveying victims of domestic abuse and receives feedback from independent sexual violence advisors and independent domestic violence advisors regarding the experience of victims. There is also the survivors’ forum and the women’s independent advisory group, the latter of which focuses specifically on violence against women and girls.

We saw evidence of the constabulary using the feedback from victims and survivors to develop some of its services. This was most evident in the constabulary’s creation of an internal domestic abuse pledge, outlining how staff who have been victims of domestic abuse offences will be recognised and supported. The pledge was developed by staff who were affected and is supported by a domestic abuse influencer network comprising volunteers across the constabulary. The network meets once a month and conducts activities such as informing supervisors of their responsibilities under the pledge.

The constabulary also has a Domestic Abuse Language Matters document, which has been shared nationally. This is designed to eliminate victim blaming language within the constabulary. However, we were unable to find evidence of this document being widely known in the constabulary.

The constabulary has invested in its response to investigating rape and serious sexual offences

The constabulary, under the leadership of the chief constable, has piloted Project Bluestone under Operation Soteria. The project combines police practitioner knowledge and that of academic experts to develop a new national operating model for the investigation of rape and other sexual offences. This refreshed approach has led to the introduction of a specialist investigation team, and a focus on perpetrator behaviour, victim and victim support, closer working with the Crown Prosecution Service and enhanced forensic recovery from digital devices. The two Project Bluestone areas – north and south – have dedicated victim engagement teams that provide support to victims from the point of reporting to the conclusion of investigations or attendance at court.

The structure and processes in the two areas are the result of academic analysis of common problems and suggested solutions in rape and serious sexual offences investigations. The constabulary’s involvement in this demonstrates its commitment to responding effectively to this challenging and sensitive area of work. However, we also found a backlog in rape and serious sexual offences investigations across criminal investigation departments and limited capacity within Project Bluestone to deal with all offences. We will continue to monitor the constabulary’s investment in this area.

The constabulary uses ancillary orders effectively to target offenders and support victims, but could increase the use of some protective powers

The constabulary has introduced a vulnerability specialist within the legal services team to support the application and use of protective orders. We saw good examples of the legal team working with specialist units such as Operation Topaz, a team of officers that tackles child sexual exploitation, to obtain civil orders to protect vulnerable people.

In general, officers demonstrate confidence in the application of domestic violence protection notices and domestic violence protection orders. But this hasn’t translated into a sustained application of notices and orders. Applications dropped from 284 in 2020–21 to 258 in 2021–22. We also found that the constabulary didn’t routinely record whether notices and orders were considered, which can make it difficult for the constabulary to understand if they are obtained routinely in the right circumstances.

The constabulary could also improve its applications for Stalking Protection Orders. It applied for only 6 of these between 1 April 2020 and 31 March 2022.

The constabulary understands trends and patterns in vulnerability

The constabulary makes good use of Qlik Sense to support understanding of patterns and trends in vulnerability. The application has a dashboard for officers to obtain information regarding domestic abuse, that lists outcomes, outstanding suspects, protective orders and other key indicators of how well the constabulary is tackling this issue.

Qlik Sense also supports officers in recognising vulnerability in specific groups. For example, it has a page regarding sex workers. This identifies trends in increased incidents targeting sex workers. This ongoing analysis has allowed the constabulary to increase efforts to protect this community from victimisation. For example, the constabulary told us that 82 percent of known sex workers now have a multi-agency risk assessment conference flag. This means that efforts to safeguard them are discussed across the constabulary and other statutory partner organisations, such as adult social care.

The constabulary can also use this data to understand gaps in its approach. The mature understanding of demand demonstrated by Qlik Sense has highlighted that the constabulary may be under-recording incidents involving the safeguarding of adults as opposed to children.

The constabulary works effectively with partner organisations to safeguard victims, but the response to vulnerability can vary

Lighthouse Safeguarding Units, which are co-funded by the office of the police and crime commissioner and Avon and Somerset Constabulary, are at three sites within the constabulary area. They ensure that victims receive the tailored support and services that they need by conducting Common Needs Assessments. These ensure victims remain updated about the progress of investigations and point them to specialist support located in the units, such as independent sexual violence advisors, independent domestic violence advisors and other commissioned support services.

The constabulary also works with partners in multi-agency safeguarding hubs (MASHs) to safeguard vulnerable adults and children. There are five MASHs across Avon and Somerset, with representation at some of these from children’s social care, adult social care, education and other key partner organisations.

Ideally, a MASH should involve physical co-location with partner organisations to ensure that effective information sharing and joint decision-making take place. This is less common in Avon and Somerset since the pandemic, but nonetheless we did find effective processes in place. For example, the constabulary has created an online portal for partner organisations to easily pass information to specialist safeguarding units. This is used to complement the information already held by the constabulary and to support weekly briefings to partner organisations regarding individual at-risk children.

We also found that referrals to the MASHs – whether in the form of BRAG, DASH or any other risk assessment – were promptly assessed and actioned, with any backlog subject to review. But we did find this response could vary dependent on the type of vulnerability being addressed. For example, we did see good examples of vulnerable adults being supported. But we also found that vulnerable adults don’t always receive the same level of service as children. The constabulary has recognised it may be under-recording the demand for safeguarding adults, and partner organisations across the MASHs routinely felt vulnerable adults received a lesser service compared to children. And the constabulary has no specific team for supporting adults at risk or investigating crimes against them.

Adequate

Managing offenders and suspects

Avon and Somerset Constabulary requires improvement at managing offenders and suspects.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the constabulary manages offenders and suspects.

The constabulary effectively identifies high-risk wanted persons, but must improve the time it takes to arrest suspects

The constabulary effectively identifies the highest-risk wanted persons by producing a ‘top 20’ wanted persons list. And the apprehension of these highest-risk wanted persons is prioritised and monitored in daily management meetings. We saw that officers would be routinely allocated above other duties to ensure these persons were arrested.

But for wanted persons who aren’t in the top 20 list, the process is less effective. And this applies to wanted persons who, although not in the list, nonetheless remain in the high-risk category. At the time of our inspection, the constabulary told us it had approximately 2,542 wanted persons with 472 of these being high risk. These wanted persons weren’t subject to the same level of oversight as those in the top 20 list.

As of 1 March 2022, the proportion of wanted persons circulated on the Police National Computer (PNC) by Avon and Somerset Constabulary who have been on the PNC for more than 6 months was 69 percent. This was an increase of 14 percentage points compared to 12 October 2020, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Proportion of wanted persons circulated on PNC by Avon and Somerset Constabulary who have been on PNC for more than 6 months between 1 August 2018 and 1 March 2022

The constabulary should also improve the amount of time taken to arrest wanted persons. While it is prompt in circulating a suspect on the PNC as wanted, the constabulary told us that at the time of our inspection, the median time for wanted persons to be arrested ranged from 41 days to 156 days, depending on the team in question.

The constabulary effectively assesses the risk registered sex offenders pose, although it should ensure all offender managers are suitably trained and low-risk offenders are managed in line with national standards

Specialist officers in the constabulary’s management of sexual offenders and violent offenders (MOSOVO) unit monitor registered sex offenders and are responsible for assessing and managing the risk these offenders pose. The constabulary uses ARMS to assess levels of risk. We found the quality of ARMS assessment to be good, with effective supervision that identified the need for any further action. And we saw good examples of joint working with the probation service and prompt referrals to the MASH.

We did find that the constabulary doesn’t routinely manage offenders in line with standards guided by the College of Policing’s authorised professional practice (APP). APP states that management of low-risk offenders can be reduced to reactive management after two low-risk ARMS assessments and three years of low-risk management. However, the constabulary allows reactive management after only one year of low-risk management. The constabulary also allows registered sex offenders with a court order to be subject to only reactive management. This is against APP and may mean that court orders are not being enforced through regular visits.

However, we did find this approach to reactive management was supported by routine and thorough checks on the offender and their circumstances instead of physical visits. The examples that we saw were isolated to those low-risk offenders being considered for reactive management, but the constabulary should consider if this enhanced checking could be conducted for higher-risk offenders as well.

The constabulary further deviates from APP by routinely allowing ‘single-crewed’ visits. This means the visit is conducted by a single offender manager. APP recommends visits be conducted by two offender managers to improve the quality of the visit and reduce the chance of manipulation by the registered sex offender.

We also spoke to several staff who hadn’t received the appropriate level of training for the offender manager role. This included a supervisor who was conducting supervision of ARMS assessments.

The constabulary makes good use of technology when monitoring registered sex offenders but doesn’t use it fully elsewhere

We found good evidence of the MOSOVO team using technology to help monitor registered sex offenders. This included digital examination equipment that officers can take to the scene and that can identify the likelihood of devices containing indecent images or prohibited material. This helps officers to make effective decisions as to when to seize digital devices as evidence and can prevent a lengthy backlog of devices waiting to be examined that don’t result in evidence being obtained.

But we did not find this equipment being used by the ICAT team. Instead, that team had to rely on examiners from the digital forensic unit to assist them if they were attending an address to make an arrest or otherwise seize digital devices. Equipment to analyse devices was available at the station for ICAT officers, but not all ICAT officers were trained in its use. And this doesn’t reduce the possibility of devices being seized unnecessarily that otherwise might be triaged at the scene.

Neighbourhood policing teams are aware of registered sex offenders in their communities and work with offender managers

The constabulary provides neighbourhood policing teams with a useful app called ‘My RSO’ that works with Qlik Sense. Teams can access maps that show the locations of registered sex offenders. These locations can be expanded to access further details about a registered sex offender, such as an overview of their risk level and recent activity.

Neighbourhood policing officers and their supervisors felt that this helped them understand the risks in their areas and recognise opportunities to take enforcement action, submit intelligence and safeguard victims. We did not find that this deeper understanding of the risk posed by registered sex offenders was universal across all neighbourhood policing teams we spoke to. However, we did see good examples of neighbourhood policing officers attending multi-agency public protection arrangement meetings, where the risk posed by offenders is discussed by partner agencies, and attending meetings with partner agency staff who supervise offenders in properties used for prison releases. We also saw that neighbourhood policing officers had short-term secondments with the MOSOVO team to enhance their knowledge of managing registered sex offenders.

The constabulary routinely considers prevention orders and effectively deals with breaches of notification requirements

Registered sex offenders are subject to restrictions to their movements and behaviour. These are known as notification requirements. Requirements could include the registered sex offender registering a change of address with the constabulary or alerting it when they apply for a new bank card. We found that the constabulary consistently records breaches of notification requirements and takes enforcement action in relation to them.

The constabulary has started the ‘Always Choose to Tell’ scheme, whereby offenders who have committed minor breaches are given conditional cautions. These cautions require the offenders to attend the scheme. The scheme, run by a local charity, addresses the root cause of the offending behaviour to try and prevent future breaches.

We also found that the constabulary applies for sexual harm prevention orders for all offenders arrested and charged by the ICAT team.

By doing this, the constabulary demonstrates a commitment to preventing future offences, as well as pursuing justice for offences already committed.

The constabulary has an effective integrated offender management programme and understands the impact of its work with offenders

The constabulary has an effective integrated offender management (IOM) programme in line with the current government strategy of creating safer communities by reducing neighbourhood crime. There are six IOM teams throughout the constabulary, which are each responsible for managing an identified group of local prolific offenders. These offenders are identified and prioritised using a risk assessment framework. The teams also use Qlik Sense to monitor risk levels of offenders.

The IOM officers work with the offenders and actively seek pathways out of offending. This can include helping them access opportunities for work and developing skills to avoid offending behaviours. IOM officers attend meetings with the probation service to offer support to prevent reoffending and conduct unannounced home visits. We found that officers found the relationship with the probation service to be productive, and IOM teams work in the same office with the probation service and representatives from the health service.

The IOM teams focus on early intervention, but also on preventing reoffending through enforcement of the law if necessary. The constabulary uses mandatory and voluntary tagging as part of its IOM programme, which helps it to remotely track offenders.

The IOM teams also assess the effectiveness of their interventions by using the national police system IDIOM (a web-based offender tracking tool, provided by the Home Office to police forces) to track reoffending rates and calculate the cost of crime committed by the offenders managed by the constabulary. The constabulary was in the early stages of using this system at the time of our inspection.

Requires improvement

Disrupting serious organised crime

We now inspect serious and organised crime (SOC) on a regional basis, rather than inspecting each force individually in this area. This is so we can be more effective and efficient in how we inspect the whole SOC system, as set out in HM Government’s SOC strategy.

SOC is tackled by each force working with regional organised crime units (ROCUs). These units lead the regional response to SOC by providing access to specialist resources and assets to disrupt organised crime groups that pose the highest harm.

Through our new inspections we seek to understand how well forces and ROCUs work in partnership. As a result, we now inspect ROCUs and their forces together and report on regional performance. Forces and ROCUs are now graded and reported on in regional SOC reports.

Our SOC inspection of Avon and Somerset Constabulary hasn’t yet been completed. We will update our website with our findings (including the force’s grade) and a link to the regional report once the inspection is complete.

Building, supporting and protecting the workforce

Avon and Somerset Constabulary is good at building and developing its workforce.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the constabulary builds and develops its workforce.

Senior leaders promote an ethical culture

Most of the officers and staff that we spoke to spoke highly of the senior officer team and said that they were seen as ethical and demonstrated the values expected of the workforce. Standards are promoted through constabulary values, which are ‘caring’, ‘courageous’, ‘inclusive’ and ‘learning’. These values are reinforced by regular communication from chief officers, such as blogs and ‘talk time’ sessions, including face-to-face engagement with the workforce. Each chief officer uses reverse mentoring, in which they are mentored by individuals of any grade within the constabulary with an underrepresented protected characteristic.

The chief officer team is willing to take bold steps to promote ethical behaviour. A recent campaign to highlight abuse of position for a sexual purpose involved placing messages in public areas to generate debate among the workforce.

The constabulary provides a platform for ethical discussions and decisions through its established ethics committee, comprising academics and trained in-constabulary representatives. Although the content of discussions is shared with the workforce, not all the officers and staff we spoke to were aware of the committee or the decisions it had taken.

The constabulary understands the well-being needs of the workforce and provides a range of preventative and reactive well-being measures

The constabulary uses a good range of data to inform its understanding of well-being. As a result, the people committee can review and analyse key issues such as trends in sickness, occupational health unit demand, and welfare support. It carries out an annual survey and pulse surveys to understand the risks to the workforce’s well-being and to measure the impact of its well-being provision. The constabulary also measures its progress through self-assessment against the National Police Wellbeing Service’s Blue Light Wellbeing Framework standards.

The constabulary has an extensive range of preventative and supportive well-being measures in place. Overall, the officers and staff we spoke to told us they felt well supported. We were told that supervisors conduct regular one-to-one discussions with their staff, and they are provided with mental health training to support them in their role. Managers use Qlik Sense to detail these discussions, to monitor workloads and to get a better understanding of the health and well-being of their workforce.

The constabulary has trained some mental health first aiders across the organisation, and continues to recruit more of them, to ensure support is readily available to individuals. Occupational health, trauma risk management and an employee assistance programme are available and accessible to support the workforce. There is a self-referral mechanism to occupational health services. The PocketBook page on the constabulary’s intranet also offers details of support options for staff.

To demonstrate its commitment to protect and support staff who are victims or survivors of domestic abuse, the constabulary has developed and introduced a pledge. This includes a domestic abuse survivors’ network, with champions trained to provide support for peers.

The constabulary provides additional psychological support to investigators in high‑risk roles. For example, those whose role involves regularly viewing indecent images of children are subject to mandatory psychological screening every six months.

The constabulary has developed a programme to ensure that dedicated support is provided to staff subject to misconduct investigations.

Despite demand challenges described earlier in this report, the proportion of police officers on long-term sickness as of 31 March 2022 was 1.4 percent. This was lower than the rate across England and Wales of 1.8 percent. The constabulary should still ensure that the long-term impacts of excessive demand are considered.

The constabulary is aware that sickness levels among police community support officers is higher than the constabulary average. Some issues have been highlighted previously in this report in relation to them being adversely affected by abstractions during Operation Hibiscus. Taking this into account, the constabulary should ensure that the welfare of all the workforce continues to be a priority.

The constabulary has a clear plan to address equality, diversity and inclusion, and has increased representation in the workforce

Chief officers are working towards an ambition of becoming the most inclusive police constabulary in England and Wales. It has a comprehensive EDI plan, led by the deputy chief constable, with an internal and external focus.

The plan includes an action plan that identifies the steps the constabulary needs to take to create a workforce that better reflects its communities. For example, the constabulary has an outreach team, comprising seven permanent members of staff representing a variety of ages, faiths, ethnicities and cultures. This diverse team bridges the gap with communities and is responsible for targeting, supporting and mentoring recruitment from under-represented community groups. It has undertaken a significant amount of positive activity and involved local communities. Internally, the team works alongside neighbourhood policing teams in working with, and understanding of, local communities.

There is an improving picture regarding the recruitment of police officers from ethnic minority backgrounds. The proportion of police officer joiners from ethnic minority backgrounds in the year ending 31 March 2022 was 6.4 percent. This is higher than the proportion of police officers already in the constabulary from ethnic minority backgrounds, which is 4.0 percent. But these figures are below the 6.7 percent of the local population from ethnic minority backgrounds. This figure is based on the 2011 Census, which was the data available at the time of our inspection. The constabulary acknowledges that there is more work to do.

Cultural intelligence training has been provided to leaders by the charity Stand Against Racism and Inequality, and focused EDI training has been provided to frontline staff. Furthermore, senior leaders have encouraged officers and staff to write blogs describing their diverse stories to make others feel more included at work.

The constabulary’s work in this area is reflected in its inclusion in the Top 100 Workplace Equality Index 2022. It was also the first constabulary to achieve the national equality standard accreditation, following independent assessment against the framework.

The constabulary understands the skills officers hold and has a clear path for future leaders, but not all officers receive regular opportunities to develop

The constabulary is working to a three-year workforce plan, supported by data in the workforce planning app that works with Qlik Sense.

A dedicated workforce planning team supports the organisation to plan its workforce and develop organisational effectiveness. It models future training and recruitment requirements. The constabulary has introduced Chronicle, a system to analyse the skills and capabilities of the workforce, to plan for its future. Core skills and expiry dates for key accreditations and training are included in the ‘My Work’ app for Qlik Sense.

Most of the workforce that we spoke to were positive about line managers offering support for individual learning and development. But we also found that not all officers receive regular opportunities to continuously develop. While there is a structured CPD programme for some officers, this wasn’t made explicitly available to the entire workforce. For example, response officers have protected training days scheduled every ten weeks, but the structured CPD for neighbourhood policing teams is less consistent. This is discussed in the ‘Preventing crime and antisocial behaviour’ section of this report, under ‘Areas for improvement’.

The constabulary supports leadership development. It is developing a leadership academy, with the primary aim of embedding an inclusive learning culture, and to improve standards and well-being across the entire organisation. With an independent consultancy, it provides leadership development programmes and resources using a range of learning and delivery methods. And it creates personal development journey maps for individuals that can be linked to the development plan in the individual performance review system to support the recording of the learning journey. The individual performance review system is how the constabulary tracks the personal development reviews conducted by supervisors. As part of the academy, each directorate in the constabulary develops plans for its own areas, focused on local leadership priorities, and where leadership development is most needed. It is too early for us to assess the leadership academy’s effectiveness at present, but we will continue to monitor this.

The constabulary has a good understanding of its recruitment needs, but could do more to understand why officers choose to leave

The constabulary has weekly meetings to monitor recruitment into key roles and provides regular reports to the governance and scrutiny board, chaired by the PCC. It has also hosted focus groups in communities to understand what would encourage more applications or remove any barriers to recruitment. For example, as a result of one focus group where police IT was perceived as dull, the constabulary updated its website to reflect how progressive and varied police IT work is in reality.

The constabulary is also seeking to better understand why members of its workforce leave. It has recently published a new retention strategy, detailing the context and challenges the constabulary faces in retaining people. It includes proposed actions based on the main issues the constabulary has identified as to why individuals or groups of officers or staff are more likely to leave the constabulary. For example, a particular focus has been placed on retaining student police officers, with a Stay Survey to be conducted at regular intervals, and a review of student officers’ abstraction levels to be carried out by the University of the West of England.

Retention is also explored in the People Survey and in exit interviews. Results are reviewed to determine ways to improve workforce retention. As a result of exit interviews held with communication centre staff, the constabulary is seeking to make improvements and has introduced a two-year tenure. There is also a pay review underway. It has also secured funding to over-recruit to ensure that communication centre vacancies continue to be filled.

But the constabulary has not yet developed a sophisticated system to help it to produce a comprehensive dataset concerning retention. A senior analyst has been appointed to carry out this work. The constabulary is also hopeful that the introduction of the Oleeo e-recruitment system will provide an opportunity to better understand all stages of the recruitment pipeline, including retention.

The constabulary has made good progress in recruiting officers through the Police Uplift Programme and the policing education qualifications framework

The constabulary has made good progress in recruiting officers through the new Police Uplift Programme and policing education qualifications framework entry programmes. It works with the University of the West of England to implement these, and it is training recruits for the Police Constable Degree Apprenticeship and the Degree Holder Entry Programme. It has a system to identify talented officers in these framework entry programmes for development and progression.

The constabulary recognises the importance of achieving its target in the Police Uplift Programme. The heads of learning and development and organisational development meet every two weeks to discuss the programme.

The constabulary has also considered ways to monitor disproportionality in progression, by reviewing candidates from ethnic minority backgrounds at each stage of the recruitment process. For example, it reviews candidates at shortlisting and interviewing stage, to understand why they receive fewer invitations to interview and conditional offers, compared with other candidates. The constabulary also uses Qlik Sense to consider disproportionality in progression. Furthermore, the constabulary changed the apprenticeship entry requirements to offer better opportunities considering diversity and inclusion.

Good

Tackling workforce corruption

Vetting and counter corruption

We now inspect how forces deal with vetting and counter corruption differently. This is so we can be more effective and efficient in how we inspect this high-risk area of police business.

Corruption in forces is tackled by specialist units, designed to proactively target corruption threats. Police corruption is corrosive and poses a significant risk to public trust and confidence. There is a national expectation of standards and how they should use specialist resources and assets to target and arrest those that pose the highest threat.

Through our new inspections, we seek to understand how well forces apply these standards. As a result, we now inspect forces and report on national risks and performance in this area. We now grade and report on forces’ performance separately.

Avon and Somerset Constabulary’s vetting and counter corruption inspection hasn’t yet been completed. We will update our website with our findings and the separate report once the inspection is complete.

Strategic planning, organisational management and value for money

Avon and Somerset Constabulary is good at operating efficiently.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the constabulary operates efficiently.

The constabulary’s strategic planning processes are supported by effective governance arrangements and analysis

The constabulary’s corporate strategy comprises four themes: service; people; digital and infrastructure. It is based on public feedback and reflects the PCC’s police and crime plan and the constabulary’s ambition to provide outstanding policing for everyone.

The action that the constabulary needs to take to achieve its priorities is clearly defined in the strategy. Senior leaders each have responsibility for priorities. These priorities refer to an integrated performance and quality framework that the constabulary has developed. This framework brings together national, regional and local priorities, and poses critical questions about performance. Each of these priorities is graded, based on the constabulary’s current position. This helps it to prepare a performance control strategy, and we saw how the constabulary management board uses this to evaluate progress.

The constabulary uses data effectively to understand resources and assets it needs to meet demand but doesn’t always provide the public with a consistent service