Overall summary

Our judgments

Our inspection assessed how good Wiltshire Police is in nine areas of policing. We make graded judgments in eight of these nine as follows:

We also inspected how effective a service Wiltshire Police gives to victims of crime. We don’t make a graded judgment in this overall area.

We set out our detailed findings about things the force is doing well and where the force should improve in the rest of this report.

Important changes to PEEL

In 2014, we introduced our police effectiveness, efficiency and legitimacy (PEEL) inspections, which assess the performance of all 43 police forces in England and Wales. Since then, we have been continuously adapting our approach and this year has seen the most significant changes yet.

We are moving to a more intelligence-led, continual assessment approach, rather than the annual PEEL inspections we used in previous years. For instance, we have integrated our rolling crime data integrity inspections into these PEEL assessments. Our PEEL victim service assessment will now include a crime data integrity element in at least every other assessment. We have also changed our approach to graded judgments. We now assess forces against the characteristics of good performance, set out in the PEEL Assessment Framework 2021/22, and we more clearly link our judgments to causes of concern and areas for improvement. We have also expanded our previous four-tier system of judgments to five tiers. As a result, we can state more precisely where we consider improvement is needed and highlight more effectively the best ways of doing things.

However, these changes mean that it isn’t possible to make direct comparisons between the grades awarded this year with those from previous PEEL inspections. A reduction in grade, particularly from good to adequate, doesn’t necessarily mean that there has been a reduction in performance, unless we say so in the report.

HM Inspector’s observations

I have concerns about the performance of Wiltshire Police in keeping people safe and reducing crime. In particular, I have serious concerns about how the force responds to the public, protects vulnerable people and makes use of its resources.

In view of these findings, I have been in regular contact with the Chief Constable, as I do not underestimate how much improvement is needed.

These are the findings I consider the most important from our assessment of the force over the last year.

The force is failing to understand and promptly identify vulnerability at the first point of contact

Wiltshire Police is missing opportunities to protect vulnerable and repeat victims of crime. It needs to improve the way it manages its calls for service so that all vulnerable people are identified. The force is often failing to complete assessments of victims’ needs.

The force needs to improve how it provides advice about preventing crime and preserving evidence when taking calls from the public.

Wiltshire Police needs to improve how it protects vulnerable people from harm

Some domestic abuse victims have received an unacceptable level of service and have continued to remain at risk.

The force is not always using alternatives to prosecution, such as prevention orders, when appropriate. And it needs to make sure that its public protection teams have enough suitably qualified staff. More positively, the force has recently developed plans to address violence against women and girls. It is committed to working collaboratively with the Wessex Tri-Force collaboration in adopting the national strategy. It is well‑placed to make progress on this in the coming months.

The force needs to improve how it plans and manages its organisational efficiency

The force’s financial and strategic planning is inadequate, and this has negatively affected its overall performance and management. The force needs to better understand the skills of its workforce. It also needs to understand how to effectively make use of these, and address any shortfalls.

The force needs to improve its understanding of the likely future demand for its services and how it can make sure it meets this demand. And it needs to show more clearly how it provides value for money.

The force needs to improve the quality of its crime investigations

The force is not supervising investigations well enough to make sure that their quality is consistently high. And it does not always follow all investigative opportunities or comply with the Code of Practice for Victims of Crime.

The force needs to improve in all areas that we assessed, but particularly in its response to the public, in protecting vulnerable people and in its organisational efficiency. Wiltshire Police has told me it intends to make progress in how it understands and protects vulnerable people, making sure it has effective and efficient plans in place to do so.

My report sets out the more detailed findings of this inspection. I will continue to monitor the force’s progress in addressing these in the coming months.

Wendy Williams

HM Inspector of Constabulary

Providing a service to the victims of crime

Victim service assessment

This section describes our assessment of the service victims receive from Wiltshire Police, from the point of reporting a crime through to its end result. As part of this assessment, we reviewed 130 case files as well as 20 cautions, and cases where a suspect was identified but the victim didn’t support or withdrew their support for police action. While this assessment is ungraded, it influences graded judgments in the other areas we have inspected.

The force needs to improve the time it takes to answer emergency calls and the identification of repeat or vulnerable victims

When a victim contacts the police, it is important that their call is answered quickly and that the right information is recorded accurately on police systems. The caller should be spoken to in a professional manner. The information should be assessed, taking into consideration threat, harm, risk and vulnerability. And the victim should get appropriate safeguarding advice.

The force needs to improve the time it takes to answer emergency calls as it is not meeting national and force standards. When calls are answered, the victim’s vulnerability isn’t always assessed using a structured process. Repeat victims aren’t always identified, which means this information isn’t taken into account when considering the response the victim should have. And not all victims are being given advice on crime prevention or preserving evidence. This may lead to the loss of evidence that would support an investigation and the opportunity to prevent further crimes against the victim.

The force does not always respond to calls for service in a timely way

A force should aim to respond to calls for service within its published time frames, based on the prioritisation given to the call. It should change call priority only if the original prioritisation is deemed inappropriate, or if further information suggests a change is needed. The response should take into consideration risk and victim vulnerability, including information obtained after the call.

The force is mostly responding to calls within its published time frames. But we found that on some occasions there were considerable delays in its response. Victims weren’t always informed of delays and therefore their expectations weren’t always met. This may cause victims to lose confidence and disengage from the process. If the force fails to attend calls within an appropriate time, victims may be put at risk and evidence may be lost.

The force allocates crimes to appropriate staff and victims are promptly informed if their crime is not going to be investigated further

Police forces should have a policy to make sure investigations are allocated to suitably trained officers or staff. The policy should also establish when a crime isn’t to be investigated further, and should be applied consistently. The victim of the crime should be kept informed of who is dealing with their case. They should also be fully informed over the decision to close the investigation.

We found that the force allocated recorded crimes for investigation according to its policy. In all cases, the crime was allocated to the most appropriate department for further investigation. On most occasions victims were updated to inform them that their crime report wouldn’t be investigated further. To manage their expectations, victims must be kept fully informed and receive an appropriate level of service.

The force is not always carrying out effective or timely investigations

Police forces should investigate reported crimes quickly, proportionately and thoroughly. Victims should be kept updated about the investigation and the force should have effective governance arrangements in place to make sure investigation standards are high.

We found that the force sometimes didn’t carry out investigations in a timely way and often didn’t complete relevant lines of inquiry. There was frequently a lack of effective supervision of investigations and investigation plans. This resulted in some ineffective investigations.

Victims were not always kept updated about the progress of investigations. This failure to consistently carry out effective, timely investigations means that victims are being let down and offenders are not being brought to justice. When domestic abuse victims withdrew their support for a prosecution, the force did not always consider the use of orders designed to protect the victims, such as a Domestic Abuse Protection Notice or Order. Obtaining such orders is an important method of safeguarding victims from further abuse in the future.

The Code of Practice for Victims of Crime requires forces to carry out a needs assessment at an early stage to determine whether victims need additional support. The outcome of the assessment and the request for additional support should be recorded. The force is not always completing this assessment, which means not all victims will get the appropriate level of service.

The force finalises reports of crimes appropriately but sometimes fails to consult the victims for their views or record them

The force should make sure it follows national guidance and rules for deciding the outcome type it will assign to each report of crime. In deciding the outcome type, the force should consider the nature of the crime, the offender and the victim. These decisions should be supported and overseen by leaders throughout the force. In some cases, offenders can be issued with a community resolution. If the community resolution is to be used correctly, it should be appropriate for the offender and the nature of the offence, and the views of the victim should be considered and recorded. In most cases we reviewed, the offender and the circumstances of the case meant that it was suitable to use this outcome. But often the force didn’t seek or consider the victim’s views.

Where a suspect is identified, but the victim doesn’t support or withdraws their support for police action, the force should have an auditable record to confirm the victim’s decision. This will allow it to close the investigation. Evidence of the victim’s decision was absent in some cases we reviewed. This represents a risk that victims’ wishes may not be fully represented or considered before the crime is finalised.

Engaging with and treating the public with fairness and respect

Wiltshire Police requires improvement at treating people fairly and with respect.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to treating people fairly and with respect.

The force engages with its diverse communities to understand what matters to them

The force has a public service board, six independent advisory groups and a Wiltshire Diverse Communities independent advisory group. In addition, the force and Office of the Police and Crime Commissioner have established a Youth Commission to engage with young people.

The force uses these bodies as ‘critical friends’, accepting advice, challenge, and constructive feedback from them on a wide range of topics. But the force should do more to demonstrate how it listens and is taking action to address what matters to its communities at a local level.

The workforce understands how to behave fairly and uses effective communication skills in its interactions with the public

Force training in preventing unfair behaviour and improving effective communication skills has been delayed by the pandemic. Despite this, many officers we spoke to showed an understanding of what constitutes unfair behaviour and how to combat this. Most said they would challenge colleagues if they felt their behaviour was not acceptable.

Many officers showed effective communication skills. They gave examples of when they had used these to deal with a difficult or volatile incident, or when speaking to someone with learning disabilities or mental health needs. They understood that often instances like these may be the only interaction someone has with the police, making it particularly important to make sure that their communication is appropriate.

The force encourages the community to get involved with policing activities

The force has an effective Citizens in Policing team that co-ordinates its volunteer programmes, such as the community volunteers and the Special Constabulary. The force has invested in special constables, providing them with personal-issue IT and accredited training to equip them to perform their role.

The force also has volunteer police cadets and a mini police programme. The aim of these is to help young people better understand policing and the effect of crime and anti-social behaviour on communities.

Requires improvement

Preventing crime and anti-social behaviour

Wiltshire Police requires improvement at prevention and deterrence.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to prevention and deterrence.

The force lacks understanding of the demand its neighbourhood policing teams are facing, and what resources it needs to manage this effectively

Since our last inspection, the force has invested in its neighbourhood teams. It now has dedicated local policing teams who work closely with communities and organisations. And it has provided problem-solving training to help these teams reduce crime and anti-social behaviour.

But we were told by neighbourhood officers that they were unable to prioritise the prevention of crime, anti-social behaviour, and vulnerability. Neighbourhood teams report that the force mainly focuses on reacting to incidents, with not enough attention given to crime prevention.

We found that senior oversight of prevention activity was limited. The force does not have a clear understanding of how much problem-solving is taking place, or how often neighbourhood officers are called on to support their colleagues in response policing. This means that the force does not understand the extent to which neighbourhood policing activities, such as community engagement and crime prevention, are taking place effectively.

The force does not carry out effective problem-solving to protect vulnerable people and reduce demand

The force uses a structured problem-solving model called OSARA (Objective, Scanning, Analysis, Response, Assessment). We found limited evidence that neighbourhood teams were carrying out effective problem-solving with other agencies. And problem-solving does not take place in other parts of the force, such as safeguarding units where there are already well-established multi-agency working arrangements. This means the force is missing opportunities to reduce harm in its communities by addressing the root causes of crime. Doing this would also help reduce demand for its services.

During the inspection, the force introduced community policing intelligence officers. This role is designed to help neighbourhood teams identify areas to focus their engagement on, and target their patrols and other activity towards. As these officers were newly introduced at the time of our inspection, we are unable to comment on whether they will lead to any improvements. The force will need to embed and evaluate the initiative to make sure it improves problem-solving and crime prevention.

The force focuses on early intervention and positive outcomes

The force’s early intervention mindset is underpinned by an Early Intervention Approach and Protocol. This aims to tackle problems for children and families before they become too difficult to reverse.

Frontline officers have been given trauma-informed training, so they are able to recognise the negative impact that adverse childhood experiences have on young people and adults. Adverse childhood experiences include abuse, neglect, or any other traumatic experience that a child may encounter, such as exposure to domestic abuse. Twenty-two neighbourhood officers have received specialist training in diverting young people from anti-social behaviour and criminal activity, and the associated risks of being exploited. This work is well structured and co-ordinated by a central team, which has good engagement with local partner agencies through the Swindon and Wiltshire Intervention for Families to Thrive programme. The force is awaiting an independent evaluation of this approach to understand its effectiveness.

The force is developing an evidence-based policing culture

The force has set up a group of officers and staff which aims to support the application of new learning and the use of research to influence future decision-making.

The group directs student officers, who carry out research as part of their training, to focus their research on force priorities and areas where learning is required. The force holds internal events called FLIPSIDE (Focus on Learning, Innovation and Problem-Solving) and publishes a quarterly internal newsletter to inform its workforce about new initiatives and good ways of working. The force hosted a virtual Southwest Regional Society of Evidence Based Policing conference in 2021, with guest speakers promoting the benefits of using research.

The force is professionalising neighbourhood policing through training and accreditation

The force has developed a Neighbourhood Policing Training Programme, which focuses on involving communities in its work and problem-solving, and follows national standards. Learners complete a course workbook, which is marked by a specially trained internal assessor, to achieve an accredited standard in neighbourhood policing.

Neighbourhood officers also receive continuous professional development through a protected learning day every five weeks. The programme includes vulnerability training, and at the time of the inspection was being run through online sessions. Officers told us that they did not always find the sessions useful, so the force should assure itself that they are relevant and effective.

Requires improvement

Responding to the public

Wiltshire Police is inadequate at responding to the public.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force responds to the public.

The force lacks understanding of the demand faced by call handlers and officers responding to calls for service, and what resources it needs to manage this effectively

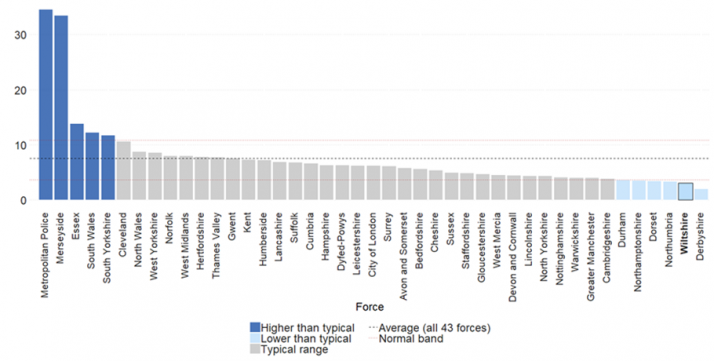

We found that the force has a call abandonment rate which exceeds the national standards required.

The force had a higher call abandonment rate (101 calls per 1,000 population) than the overall rate for England and Wales in the 12 months to 30 September 2021. But it has no accurate or detailed understanding of this trend due to a lack of accurate information.

Number of 101 calls per 1,000 population received in the 12 months to 30 September 2021

During our inspection, leaders were unable to tell us about the demand the force faced. And the distribution of resources to meet predicted demand was ineffective. We found that demand faced in the control room was generally managed in isolated teams, with limited sharing of information within the control room and with other parts of the force.

People who first contact the force reach a switchboard. But the operators taking calls here can’t record details of incidents or take action to deploy officers. During our inspection, we listened to victims of crime contacting the force with no details being recorded and no assessment of risk carried out. One case involved a vulnerable female alleging racial harassment from a known suspect. The caller told an operator about the level of risk she faced before having her call directed internally to another call handler queue to wait again for a response. There was a real risk of the caller abandoning the call before the force recorded her contact details.

The demand on the switchboard is not well understood. During our inspection we noted that several victims used it to get updates for their crimes. This increases the demand on the force. It also indicates that officers are not keeping victims well enough informed about how their crimes are being taken forward.

The switchboard internally transfers callers to a call handler in the Command Control Centre, where they may wait again to make a report. This creates a risk that callers will abandon their call due to the wait and their information will be lost. This could mean callers do not report their concerns and that vulnerable people are waiting in control room queues for a long time.

The force needs to make sure it attends calls for service in line with its published attendance times

In our audits, we found some significant delays in responding to priority calls, which should be attended within one hour. This included calls from victims of the most serious crimes, where a delayed attendance could lead to the victim disengaging or missed opportunities to preserve or obtain evidence.

We were told that response teams lacked resilience when student officers were taken away from their duties to complete their training, in line with the National Policing Degree as set out by the College of Policing. So the force is not always responding to incidents as well as it would like. In addition, some officers told us that they lacked the training required to drive vehicles to emergency calls. This was in part due to restrictions on face-to-face training during the pandemic. Officers also told us there was a lack of available and roadworthy vehicles, which limited their ability to respond to incidents promptly.

The force should improve its scrutiny of its call handling performance

On 31 May 2022, the Home Office published data on 999 call answering times. Call answering time is the time taken for a call to be transferred to a force, and the time taken by that force to answer it. In England and Wales, forces should aim to answer 90 percent of these calls within 10 seconds.

Since the Home Office hadn’t published this data at the time we made our judgment, we have used data provided by forces to assess how quickly they answer 999 calls. In the future, we will use the data supplied by the Home Office.

The force monitors call handling data for emergency and non-emergency calls at a fortnightly meeting, but using limited data. The force should scrutinise more in-depth information to get a better overview of call handling performance that allows it to accurately identify themes and trends. This will support the force in understanding the areas it needs to improve in, and inform the action it should take.

The force should improve how it reports and investigates missing children

The force is not following Authorised Professional Practice when responding to reports of missing children. We found that the Command Control Centre was frequently recording a ‘concerns for welfare’ incident when a child was reported missing. This would not always result in any activity to find them until a second call or a review up to four hours later. We also found delays in risk assessments and delayed activity to find missing children. A missing person report should be recognised as an opportunity to identify and address risk. Police action and resources should be directed in the most effective way to keep the most vulnerable people in the community safe.

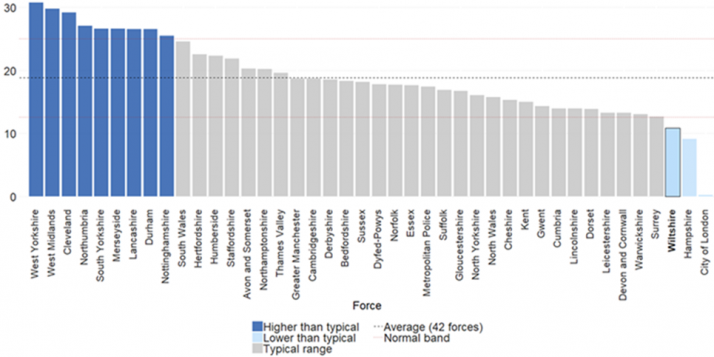

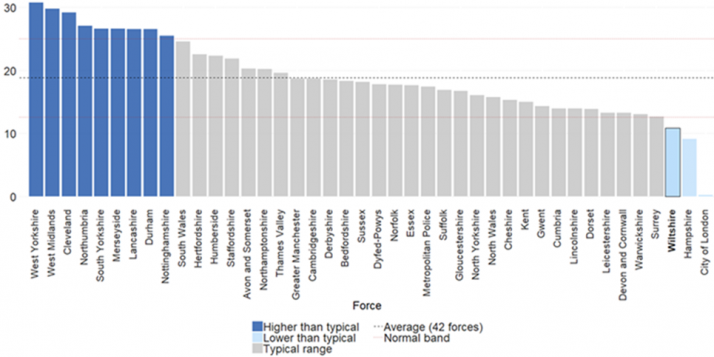

Number of individual missing children per 1,000 population in the year ending 30 September 2021

Many officers told us that the system used to record missing person enquiries is not fit for purpose. At the time of the inspection the force information management system required an update. Officers told us that data from a spreadsheet they used was often lost because the document could not be updated by more than one person at a time. This meant that information and records of actions were at risk of being frequently lost, reducing the effectiveness and timeliness of investigations. Data integrity is critical in cases of repeat or vulnerable children and adults reported missing. Failing to effectively manage this data may prevent the force from doing all that it can to protect the most vulnerable people.

The force should develop the ways in which the public can contact the force

Wiltshire Police has an outstanding Area for Improvement from our 2018/19 inspection, stating that it should improve its engagement with the public. This still applies, as digital methods available to the public to contact the force are currently limited.

At the time of our inspection the force had recently begun using the national online platform, Single Online Home, where the public can report crimes and incidents. Such investment makes the force more accessible to the public and makes it easier for vulnerable victims of crime to report incidents. It supports the force in protecting the most vulnerable people by providing links to request information about potential domestic violence or sexual offenders via the domestic violence disclosure scheme and child sex offender disclosure scheme.

Alternative contact channels add value to a force because if the public trusts and uses these, then demand from emergency and non-emergency calls will reduce. By offering a broader range of channels that are managed and appropriately risk assessed in a timely manner, the force will be more accessible to the public of Wiltshire. This will help Wiltshire Police to engage with its communities in a way that suits them, and may allow for queries to be diverted to more appropriate channels, including other agencies.

The force should make sure it supports its communications centre staff

Officers and staff working in the force communications centre told us they did not have regular one-to-one meetings with managers. These are important as they provide an opportunity for staff to talk about what support or training they may need. They also give managers time to discuss changes, review performance and support wellbeing.

During the pandemic the force paused face-to-face training with call handlers to make sure staff were safe. At the same time there were increased levels of demand and absence in the control room, which also contributed to training days being cancelled.

At the time of the inspection the force had recently reintroduced these training opportunities. Continuous professional development gives staff the opportunity to improve their knowledge and skills, which is likely to have a positive impact on performance and staff retention.

The force should support and develop its supervisors of initial responders to provide effective leadership

Wiltshire’s workforce profile reflects the relative lack of experience seen in many forces across England and Wales, with a high proportion of new officers recruited as part of the national Uplift programme. Eighty percent of officers in community policing teams, for example, have less than six years’ service, and half are student officers with fewer than two years’ service. Our inspection activity found that student officers are often being mentored and supported by inexperienced colleagues.

Many supervisors told us they lacked training on golden hour principles, which give officers the guidance to identify actions needed at the start of an investigation. Many supervisors also told us that they do not have the skills or confidence to manage inexperienced staff effectively. And many officers who had recently become inspectors felt that they were not offered enough training or development to give them the skills they needed.

The force acknowledges that this is a deficiency. At the time of the inspection it was developing a leadership and continuing professional development programme to support sergeants. We did not see enough evidence to assess the effectiveness of this training during the inspection. Failing to support supervisors and managers to reach appropriate professional standards will reduce the quality of the service the force offers to the public. It will weaken the support given to frontline officers and lead to a poor understanding of risk and criminal investigations. This can lead to victims feeling let down.

The force seeks advice from mental health experts to help inform and improve its decision-making

The force’s commitment to supporting people it encounters who are experiencing mental health issues is shown through its effective collaboration with the Wiltshire and Swindon Health Care NHS Trust. There are currently 6 full-time mental health practitioners who provide 24/7 support to the force control centre and frontline officers. The service makes sure that the force and mental health services work together effectively to give appropriate care to people in crisis.

This represents a significant financial investment by the force. But it can also be seen as a cost-effective way of managing frontline resources, such as by reducing the time officers spend with a person in crisis or at a designated place of safety. Supporting the early intervention of mental health practitioners may lead to fewer people being detained under mental health legislation.

Inadequate

Investigating crime

Wiltshire Police requires improvement at investigating crime.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force investigates crime.

The force lacks understanding of the crime demand it faces and what resources it needs to manage this effectively

The force has the second lowest crime severity score in England and Wales. This is based on the severity of crimes per 1,000 population, with each crime given a weighting. More serious crime is given a larger weighting so the crime scores account for the harm caused to communities. This means that Wiltshire records a very low amount of serious crime. Despite this, the force does not have the capacity or capability to manage its crime investigations effectively.

The force has carried out some assessment of its challenges arising from its current crime demand. But it needs to do this in a more in-depth and data-informed way as there is little indication that the force understands its future demand. The force needs a comprehensive workforce plan that considers investigative and specialist skills to make sure it has the capacity and capability needed to meet that demand.

The force does not have enough detectives. It has had a number of detective vacancies since 2019. These exist in both its criminal investigation department (CID) and safeguarding teams, which manage more serious and complex investigations.

The force has been aware of these gaps, which are part of a recognised national policing problem. But it does not have an effective long-term recruitment plan to increase capacity. The force should recognise that the shortfall puts extra pressure on its existing workforce. We were told by experienced detectives that they were required to support inexperienced staff working towards their accreditation on top of their own workload.

The force should make sure it has effective governance arrangements in place at all levels to support quality investigations

The force has some governance structures in place to oversee investigations and investigation standards. It carries out audits, but these do not always include enough of both quantitative and qualitative information concerning the management of victim care and of the investigation from beginning to end. We found that too often managers from different departments (such as the Crime and Communications Centre, local policing teams, CID and public protection) were not working together effectively to improve standards.

The force needs to give clear guidance on what is required to make sure that investigations are completed to a good standard and victims are given a high level of service. Senior leadership should make sure there are structured and effective processes to assess investigation standards, and hold supervisors and investigators to account at all levels.

Some investigations are not allocated appropriately

Our audit found that most crimes were allocated appropriately according to the force’s crime allocation policy. But there were some occasions where officers and supervisors did not have the appropriate experience to investigate some serious and complex crimes. The force should make sure that it allocates investigations to appropriately skilled and accredited staff based on threat, harm, and risk.

The force should improve its ability to retrieve digital evidence from mobile phones, computers, and other electronic devices

The force has introduced some digital hubs in police stations and there is a prioritisation process for urgent cases to be dealt with quickly. But officers are still experiencing delays in getting digital evidence. This is a national issue affecting the timeliness and quality of investigations across forces.

Requires improvement

Protecting vulnerable people

Wiltshire Police is inadequate at protecting vulnerable people.

Prevalence of domestic abuse related incidents across forces in England and Wales in the 12 months to 30 September 2021

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force protects vulnerable people.

The force does not have a good enough understanding of the quality of safeguarding it provides

Officers who identify a child or adult who needs extra safeguarding support will complete a referral to specialist teams, known as a public protection notice. We found that insufficient supervision and scrutiny of these reports in multi-agency safeguarding hubs (MASH) meant that not all crimes had been recorded. This could mean that action is not taken to make sure that vulnerable children or adults are given the protection they need.

We also found a lack of scrutiny of missing children reports, which meant that these were not always reported correctly. This meant that opportunities to find children and share information with other safeguarding agencies to reduce harm were missed. The force should make sure that the information it uses to understand performance is complete and accurate. This is so that senior and local managers can understand demand and how well teams are protecting the most vulnerable people.

Encouragingly, the force has recently introduced a dedicated quality assurance capability. This supports its understanding of good performance. The force should make sure that audits it completes have a clear focus and structure.

Number of DVPO applications per 1,000 domestic abuse related offences recorded in the 12 months to 30 September 2021

The force contributes to MASH but needs to make sure its staff are adequately trained to perform their role effectively

The force has dedicated staff in two MASH. These are focused on both adults and children and based in Swindon and Trowbridge. But our inspection found that these MASH staff had not been given specialist training to support them to perform their role. We found that this was reducing the force’s ability to identify risk and cases where immediate safeguarding action was required. In addition, case history research is not always being completed. This may lead to missed opportunities to give the right level of support or to prevent escalation and increased frequency of harm.

The force has recognised this as a gap and is seeking to recruit more supervisors.

The force has improved its use of protective powers to safeguard vulnerable people and victims

Since July 2019, the force has improved its processes for the public to report concerns about named individuals via the child sex offender disclosure scheme and domestic violence disclosure scheme, often known as Sarah’s Law and Clare’s Law. The scheme allows the force to share information about offenders with people it considers may be at risk of harm.

The force understands which roles in safeguarding pose a high risk to wellbeing, and is focused on making sure the workforce receives the support it requires

The force has identified many high-risk roles as eligible for enhanced wellbeing support. Officers in these roles complete regular psychological assessments known as RABMs (risk assessment based medicals) to identify people who need additional support. While investigators generally spoke positively about welfare and wellbeing support they got from their supervisors and managers, many officers in safeguarding teams told us that high workloads were creating a strain on their wellbeing.

Inadequate

Managing offenders and suspects

Wiltshire Police requires improvement at managing offenders and suspects.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force manages offenders and suspects.

The force has a process for dealing with outstanding suspects and offenders, but could do more to bring offenders to justice

The force reviews and highlights outstanding suspects at daily management meetings and team briefings. It ran a ‘Wanted in Winter’ social media campaign during Advent in 2021. This achieved some success in encouraging the public to share information to locate outstanding offenders.

The force has a process in place for circulating details of offenders on the Police National Computer. But it should review its guidance to officers to make sure this is done in a timely manner to reduce offending and protect the public.

The force allows suspects to attend a police station voluntarily (voluntary attendance) rather than arresting them according to the necessity criteria set out in legislation. We found that the process for recording whether a suspect was voluntarily interviewed was inconsistent. And decisions to arrest instead did not always have supervisory oversight. The force should gather information on the use of voluntary attendance, so it can effectively scrutinise and monitor this at local and force performance meetings. This is important to make sure that offenders who pose the greatest risk of causing harm are appropriately detained.

The force uses a nationally approved risk assessment tool, the active risk management system, to risk assess registered sex offenders (RSOs)

The management of sexual or violent offenders (MOSOVO) team operates in accordance with Authorised Professional Practice and uses the active risk management system to assess the risk offenders pose to the public. Offender managers are trained to use this tool and carry out assessments annually unless a significant change is identified.

The force is not currently following national guidance relating to the end of licence conditions for people who have been released from prison. The ending of licence conditions represents a significant change for offenders and requires a new risk assessment. But the force is not always carrying out new assessments. This approach does not acknowledge the risk of reduced monitoring that results from the end of licence conditions.

The force is improving awareness of registered sex offenders in local policing teams

We found some awareness of RSOs in local policing teams. The force is seeking to improve how it briefs officers about RSOs. Offender managers recognise that stronger working relationships result in better awareness and working together to manage offenders. But the force needs to be more consistent in providing information to officers and police community support officers, so that they are clear on what they can do to reduce the risk offenders pose to public safety. It is essential that officers can identify opportunities to submit intelligence and, where necessary, take enforcement action to help keep vulnerable people safe.

During our inspection, the force introduced a new IT system called Beat Profiles, which highlights the status of individual RSOs to local neighbourhood teams. The system was not yet embedded, so it is too soon to comment on the effectiveness of the review at this stage.

The force works effectively with other organisations to manage offenders

The force engages positively with local multi-agency public protection arrangements (MAPPA). It has recently appointed a dedicated MAPPA co-ordinator to support the screening of referrals to be considered for inclusion in the MAPPA process. The role will also focus on increasing access to MAPPA training and increasing awareness of MAPPA in the wider force. The organisations that the force works with in MAPPA acknowledged that effective partnership working was taking place.

The force has an effective integrated offender management (IOM) programme

The force has an IOM programme for offenders who pose the greatest threat, risk, and harm. The IOM unit (which consists of four police constables, a co-ordinator and one manager) was established in 2020. This is aligned with the refreshed national policy and structure. We found that the unit had a clear focus and worked well in partnership to support the rehabilitation of offenders.

The force uses a scoring tool to assess information and intelligence relating to offender activity (including data from other organisations) to decide whether offenders are to be managed under the IOM programme. Current participants include offenders with known links to serious theft, serious and organised crime (SOC), and violence such as domestic abuse. The unit has established monitoring processes to score and manage offenders and uses intelligence to support measures to reduce crime and offending.

The IOM unit shares details of offenders in the programme with community policing teams via the force briefing system for information and awareness. This encourages officers to gather intelligence and submit relevant information.

The force should improve its understanding of the benefits of its IOM programme to make sure its current model is evidence based

The force has a process for diverting people away from criminal behaviour, which includes a domestic abuse perpetrator programme. This process now takes place within the structure of the IOM. But the force has not carried out any analysis of the success of its IOM programme since it began in 2020. Doing this would help the force and its partner organisations understand what resources and interventions are needed to help reduce offending by the offenders they manage. It would also support a better understanding of the programme’s costs and benefits to make sure it offers value for money and value for society.

The force routinely considers preventative or ancillary orders to protect the public from the most dangerous offenders

Sexual harm prevention orders are requested by the child internet exploitation team or MOSOVO team for all applicable cases. And there is guidance to support other teams in the force to issue similar orders effectively. The force has invested in technology and training to support its workforce to proactively monitor these orders and identify any further offending. All breaches are recorded and decisions on the force’s response to these are made on a case-by-case basis. This is important to protect the public from the most dangerous offenders.

Requires improvement

Disrupting serious organised crime

We now inspect serious and organised crime (SOC) on a regional basis, rather than inspecting each force individually in this area. This is so we can be more effective and efficient in how we inspect the whole SOC system, as set out in HM Government’s SOC strategy.

SOC is tackled by each force working with regional organised crime units (ROCUs). These units lead the regional response to SOC by providing access to specialist resources and assets to disrupt organised crime groups (OCGs) that pose the highest harm.

Through our new inspections we seek to understand how well forces and ROCUs work in partnership. As a result, we now inspect ROCUs and their forces together and report on regional performance. Forces and ROCUs are now graded and reported on in regional SOC reports.

Our SOC inspection of Wiltshire Police hasn’t yet been completed. We will update our website with our findings (including the force’s grade) and a link to the regional report once the inspection is complete.

Building, supporting and protecting the workforce

Wiltshire Police requires improvement at building and developing its workforce.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force builds and develops its workforce.

The force needs an effective understanding of the current skills of its workforce and the learning and development needs of its staff

The force does not have a good understanding of the current skills of its workforce. It doesn’t have an accurate record of the skills currently available to it and isn’t able to predict the skills it will need in the future. This means the force is unable to effectively plan future training requirements.

The lack of a clear understanding of current skills and capabilities means the force doesn’t have a good understanding of its future needs. It has not effectively assessed its future workforce requirements based on its skills and capabilities gaps and on changing demand.

For example, the force is aware it doesn’t have enough detectives but doesn’t have a long-term plan to address this. If it had a better understanding of its workforce’s skills, it could target its internal and external recruitment initiatives more effectively. It is missing the opportunity to fill some skills gaps and make sure the workforce is equipped to respond appropriately to demand.

The force has a new employee record management programme which will support organisational planning once it is embedded.

The force has governance in place to promote an ethical and inclusive culture

The force’s equality, diversity and inclusion strategy is aligned to the National Police Chiefs Council’s equality, diversity and inclusion strategy. All force networks and associations are represented at the Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Board.

The force has an Ethics and Transparency Board. This is led by the chief officer team, who communicate regularly with the workforce about conduct and behaviour. Standards of ethical behaviour form part of annual performance development reviews for officers and staff. Most personnel we spoke to told us they were proud to work for Wiltshire Police and that they understood the Code of Ethics and how it applied to their work. The force uses Crimestoppers as its confidential integrity line for officers and staff to report concerns about breaches in behavioural standards.

The force should make sure it has a process recognised by its workforce to refer and discuss ethical concerns

The force has an ethics committee, which meets quarterly with an independent external chair. Many of the officers and staff we spoke to did not know about the committee and the meetings we observed mainly heard dilemmas raised by senior managers. The force should make sure its workforce has the necessary information and opportunity to refer matters that affect it to the committee. All personnel should be encouraged to participate in its discussions and benefit from the decisions it makes.

The force has worked hard to reflect the community it serves in its workforce

The force has set recruitment priorities to improve the diversity of its workforce and to better reflect the community it serves. It has sought to attract applications from under-represented groups.

The force has a dedicated positive action team which supports potential recruits with their applications. But some officers and staff who had benefited from this told us that the support ended once they had joined the organisation, and that they lacked long-term development opportunities. The force should consider how it provides development opportunities to under-represented groups to support their retention and progression.

The force is making good progress within the policing education qualifications framework

Progress in recruiting new officers against the force’s Uplift plan is scrutinised effectively by senior leaders. The force works with the University of South Wales to provide initial police training in accordance with the policing education qualifications framework, degree-holder entry programme and the police constable degree apprenticeship. Student officers and supervisors told us of the challenges of coping with operational demands as well as their studies. This is a national concern, and at the time of our inspection Wiltshire Police were seeking to address this by providing extra protected learning days for students. The force should continue to be mindful of the impact this extra absence has on the remaining officers in the response teams.

The force has plans for improving workforce wellbeing

The force has a wellbeing strategy to improve the wellbeing of its workforce. This is supported by a delivery plan that is aligned to the performance indicators in the College of Policing’s Blue Light Wellbeing Framework. A better evaluation of the action the force has taken so far on wellbeing would support it in understanding what its workforce needs and what measures work best.

There is a good range of preventative and supportive measures in place to improve wellbeing. Everybody we spoke to was aware of the wellbeing arrangements. The workforce told us they were able to access them and supported to do so by line managers.

The force has a well-respected occupational health unit. This runs an online wellness portal which includes topical information and provides links to resources and support groups. The portal publishes a quarterly newsletter containing news, information, and guidance to support health and wellbeing. The force has also signed up to the ‘1TeamActive’ programme, a police initiative providing health and lifestyle advice for people not normally involved in sport or exercise. And the force offers access to Health Assured, an employee assistance programme to support stress and mental health management.

The force recognises the wellbeing risk to officers and staff in high-risk areas of work such as safeguarding and public protection. We were told that the occupational health unit had received a high number of wellbeing referrals from child abuse investigation team officers. This had led to the force recognising the impact these officers’ work was having on their personal wellbeing and their ability to protect the most vulnerable people.

Although the force is making good efforts to improve the wellbeing of its workforce, these are sometimes being undermined by the increased pressures and demands being placed on the workforce. The force’s actions are often taken in response to immediate pressure rather than addressing its causes. If the force was more effective in developing ways of working to manage its demand, its workforce would be under less strain and as a result would likely need less reactive support.

Vetting and counter corruption

We now inspect how forces deal with vetting and counter corruption differently. This is so we can be more effective and efficient in how we inspect this high-risk area of police business.

Corruption in forces is tackled by specialist units, designed to proactively target corruption threats. Police corruption is corrosive and poses a significant risk to public trust and confidence. There is a national expectation of standards and how they should use specialist resources and assets to target and arrest those that pose the highest threat.

Through our new inspections, we seek to understand how well forces apply these standards. As a result, we now inspect forces and report on national risks and performance in this area. We now grade and report on forces’ performance separately.

Wiltshire Police’s vetting and counter corruption inspection hasn’t yet been completed. We will update our website with our findings and the separate report once the inspection is complete.

Requires improvement

Strategic planning, organisational management and value for money

Wiltshire Police is inadequate at operating efficiently.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force operates efficiently.

The force lacks an understanding of future demand and lacks effective plans to make sure it has the right resources in place to meet future needs

The force does not have plans in place to manage future demand, and there is little indication that it understands the future demand it will face. The force does not have an effective understanding of the current skills of its workforce, nor its training and development needs.

The force should improve its overall analysis of these issues. And it needs to create a comprehensive workforce plan to make sure that it has the capacity and capability to meet future demand, particularly in certain areas such as investigations. There are not enough detectives in the force. This has a been a problem since 2019. There are vacancies in the CID and safeguarding teams, which manage the force’s more serious and complex investigations. In addition, the response teams are under-resourced.

The force is aware of these gaps, but does not have effective long-term plans to increase capacity. The lack of investment and plans has placed extra pressure on the existing workforce. Detectives are required to support inexperienced staff working towards their accreditation on top of their own workloads. This is not sustainable.

The force lacks a detailed financial plan that demonstrates it can meet future demand

The force’s Medium Term Financial Plan confirms that in 2021/22 the force will deliver a balanced budget, that there is enough capital financing to support its plans for the year, that it holds enough reserves and that the council tax precept rise is in line with government thresholds.

Information given to us by the force indicates that its general reserves are low. The force has carried out a comprehensive review of its reserves, which shows a steady reduction year on year. In March 2017, force reserves stood at £20.2m in total (including a capital development reserve of £9.8m). By the end of March 2022, they are expected to be £11.9m in total (with the capital development reserve used up completely). By March 2024, total reserves are set to fall further to £6.5m, again with no capital development reserve.

The force states that it needs to save £1.39m in the 2022/23 financial year and has identified savings of £0.941m for that period. Based on these figures, the force needs to make further savings of £449,000 this financial year. The identified potential savings of £0.941m are to be made through budget adjustments, including changes to staff vacancy management and a reduction in community support officers. But these are not linked to improving effectiveness or efficiency. We found limited evidence that a clear savings plan was in place.

Without a detailed savings plan, it is not clear how the force will make further savings or how it will maintain sufficient reserve levels in future years.

The force benefits from working with other forces and actively seeks opportunities to improve services through collaboration

There is evidence of Wiltshire Police working effectively in collaboration with other forces in the Southwest region, for example in the multi-force Major Crime Investigation Team and forensic services. Collaboration activities are currently overseen by a programme team and are incorporated into several governance boards. Examples include the Gateway Board and Strategic Change and Performance Board, which are both proving effective.

The force has indicated that it is planning to appoint a strategic improvement and support officer to focus on identifying and supporting new collaborative ventures. It has a clear collaboration strategy and a governance structure that enables collaborations to be managed effectively. But it needs to improve its process for monitoring and assessing the benefits of collaboration. This was highlighted in the 2020 PEEL spotlight report The Hard Yards as well as during our inspection.

Inadequate

About the data

Data in this report is from a range of sources, including:

- Home Office;

- Office for National Statistics (ONS);

- our inspection fieldwork; and

- data we collected directly from all 43 police forces in England and Wales.

When we collected data directly from police forces, we took reasonable steps to agree the design of the data collection with forces and with other interested parties such as the Home Office. We gave forces several opportunities to quality assure and validate the data they gave us, to make sure it was accurate. We shared the submitted data with forces, so they could review their own and other forces’ data. This allowed them to analyse where data was notably different from other forces or internally inconsistent.

We set out the source of this report’s data below.

Methodology

Data in the report

British Transport Police was outside the scope of inspection. Any aggregated totals for England and Wales exclude British Transport Police data, so will differ from those published by the Home Office.

When other forces were unable to supply data, we mention this under the relevant sections below.

Outlier Lines

The dotted lines on the Bar Charts show one Standard Deviation (sd) above and below the unweighted mean across all forces. Where the distribution of the scores appears normally distributed, the sd is calculated in the normal way. If the forces are not normally distributed, the scores are transformed by taking logs and a Shapiro Wilks test performed to see if this creates a more normal distribution. If it does, the logged values are used to estimate the sd. If not, the sd is calculated using the normal values. Forces with scores more than 1 sd units from the mean (i.e. with Z-scores greater than 1, or less than -1) are considered as showing performance well above, or well below, average. These forces will be outside the dotted lines on the Bar Chart. Typically, 32% of forces will be above or below these lines for any given measure.

Population

For all uses of population as a denominator in our calculations, unless otherwise noted, we use ONS mid-2020 population estimates.

Survey of police workforce

We surveyed the police workforce across England and Wales, to understand their views on workloads, redeployment and how suitable their assigned tasks were. This survey was a non-statistical, voluntary sample so the results may not be representative of the workforce population. The number of responses per force varied. So we treated results with caution and didn’t use them to assess individual force performance. Instead, we identified themes that we could explore further during fieldwork.

Victim Service Assessment

Our victim service assessments (VSAs) will track a victim’s journey from reporting a crime to the police, through to outcome stage. All forces will be subjected to a VSA within our PEEL inspection programme. Some forces will be selected to additionally be tested on crime recording, in a way that ensures every force is assessed on its crime recording practices at least every three years.

Details of the technical methodology for the Victim Service Assessment.

Data sources

Stop and search

We took this data from the November 2021 release of the Home Office Police powers and procedures: Stop and search and arrests statistics. The Home Office may have updated these figures since we obtained them for this report.

Calls received

We collected this data directly from all 43 police forces in England and Wales. This data is as provided by forces in May 2021 and covers the year ending 31 March 2021.

Missing children

We collected this data directly from all 43 police forces in England and Wales. This data is as provided by forces in May 2021 and covers the year ending 31 March 2021.

Domestic abuse related incidents and crimes

We collected this data directly from all 43 police forces in England and Wales, though not all forces were able to provide data. This data is as provided by forces in May 2021 and covers the year ending 31 March 2021.

Domestic Violence Protection Orders

We collected this data directly from all 43 police forces in England and Wales. This data is as provided by forces in May 2021 and covers the year ending 31 March 2021.