Overall summary

Our judgments

Our inspection assessed how good the Metropolitan Police Service is in 11 areas of policing. We make graded judgments in 10 of these 11 as follows:

We also inspected how effective a service the Metropolitan Police Service gives to victims of crime. We don’t make a graded judgment in this overall area.

We set out our detailed findings about things the force is doing well and where the force should improve in the rest of this report.

Important changes to PEEL

In 2014, we introduced our police effectiveness, efficiency and legitimacy (PEEL) inspections, which assess the performance of all 43 police forces in England and Wales. Since then, we have been continuously adapting our approach and this year has seen the most significant changes yet.

We are moving to a more intelligence-led, continual assessment approach, rather than the annual PEEL inspections we used in previous years. For instance, we have integrated our rolling crime data integrity inspections into these PEEL assessments. Our PEEL victim service assessment will now include a crime data integrity element in at least every other assessment. We have also changed our approach to graded judgments. We now assess forces against the characteristics of good performance, set out in the PEEL Assessment Framework 2021/22, and we more clearly link our judgments to causes of concern and areas for improvement. We have also expanded our previous four-tier system of judgments to five tiers. As a result, we can state more precisely where we consider improvement is needed and highlight more effectively the best ways of doing things.

However, these changes mean that it isn’t possible to make direct comparisons between the grades awarded this year with those from previous PEEL inspections. A reduction in grade, particularly from good to adequate, doesn’t necessarily mean that there has been a reduction in performance, unless we say so in the report.

HM Inspector’s observations

For a considerable time, I have had concerns about several aspects of the Metropolitan Police Service’s (MPS) performance. Explanations of these appear in various inspection reports.

A notable example, from March 2022, is our inspection of the MPS’s counter corruption arrangements and other matters related to the Daniel Morgan Independent Panel. In this report, we described a range of systemic failures. These were not just in relation to counter corruption but more general matters too, such as the quality of basic supervision provided to officers.

This report describes many successes and some examples of innovation. However, it also raises serious concerns about how the force responds to the public and the level of understanding the force has about its demand and its workforce.

In view of these findings, we have taken the decision to place the MPS into our Engage process of monitoring. This will give the force greater access to assistance from HMICFRS, the College of Policing, the Home Office and other law enforcement agencies to make the required improvements. These are the findings I consider most important from our assessments of the force over the last year.

The force must get better at how it responds to the public

The force doesn’t have the capacity in its call handling teams to meet the demand for service in a timely way. It doesn’t meet the national thresholds for answering calls. Its response to vulnerable people isn’t consistent, and it isn’t always based on effective risk assessment.

But the force does allocate incidents to suitably trained staff, and its subsequent attendance is usually within its set target times.

The force should record a victim’s decision to withdraw support for an investigation or to support an out-of-court disposal or caution, as well as their reasons

The force isn’t correctly documenting the decisions of victims to withdraw from an investigation or to accept an out-of-court disposal, such as a community resolution or caution. It is important to record victims’ wishes to support the criminal justice process and to understand what is stopping victims from being able to complete the investigation process.

The quality of the investigation of crime is improving, but supervision isn’t always effective

Since we inspected the force in 2019, it has invested time and money into developing its investigative capacity and improving crime allocation. The force uses an effective decision-making process to make sure it consistently investigates the crimes that involve the most risk and are most likely to be solved.

The force has policies in place for supervising investigations, but supervisors don’t always have the capacity to comply with these. A high proportion of inexperienced staff and a lack of experienced tutors means that supervisors are often teaching staff how to investigate crime, rather than supervising them. All investigations should be reviewed by a supervisor.

The force is innovative in developing new techniques to improve how it collects evidence and identifies offenders

The force has developed a new forensic technique for detecting the presence of blood on dark clothing. It has also developed a new rapid testing kit for drink spiking cases, and it is piloting the use of DNA processing units in its custody suites.

The force is good at preventing crime and anti-social behaviour

We found that officers understood the three strategic priorities of prevention, information and collaboration, and applied these in their local crime prevention initiatives. The force has dedicated neighbourhood teams in each ward. We found that staff were working hard to build links with their communities and to widen the variety of engagement techniques they used. The force uses the scan, analyse, respond, assess (SARA) problem-solving model effectively with other organisations to help prevent crime and anti-social behaviour. But it needs to make sure it is accurately recording incidents of anti-social behaviour.

The force should improve its understanding of its demand and of the capability, capacity and skills of its workforce

The force doesn’t fully understand the capability and capacity of its workforce, and it lacks a detailed understanding of its workforce’s skills. This has led to an unfair allocation of work, which puts undue pressure on some staff. This in turn affects how it provides services and makes it harder to use resources efficiently. The force needs to develop a more comprehensive understanding of demand to make sure that its workforce can meet this now and in future.

My report sets out the more detailed findings of this inspection. The effort required to make the improvements needed should not be underestimated, and I will continue to monitor the force’s progress.

Matt Parr

HM Inspector of Constabulary

Providing a service to the victims of crime

Victim service assessment

This section describes our assessment of the service victims receive from the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS), from the point of reporting a crime through to the end result. As part of this assessment, we reviewed 165 case files as well as 20 cautions, community resolutions and cases where a suspect was identified but the victim didn’t support or withdrew support for police action. While this assessment is ungraded, it influences graded judgments in the other areas we have inspected.

The force needs to reduce the time it takes to answer emergency and non‑emergency calls

When a victim contacts the police, it is important that their call is answered quickly and that the right information is recorded accurately on police systems. The caller should be spoken to in a professional manner. The information should be assessed, taking into consideration threat, harm, risk and vulnerability. And the victim should get the right safeguarding advice.

The force isn’t answering calls quickly enough and in many cases it is failing to meet national standards. When calls are answered, the victim’s vulnerability isn’t always assessed using a structured process. Repeat victims aren’t always identified, which means this isn’t considered when deciding what response the victim should have. Call handlers aren’t always giving victims advice on how to prevent crime and preserve evidence.

In most cases, the force responds promptly to calls for service

A force should aim to respond to calls for service within the time frames it has set, based on the prioritisation given to the call. It should change call priority only if the original prioritisation is deemed incorrect, or if further information suggests a change is needed. The response should take into consideration risk and victim vulnerability, including information obtained after the call.

On most occasions the force responds to calls well. But sometimes it doesn’t attend incidents within its set timescales. Victims aren’t always informed of delays, and sometimes their expectations aren’t met. This may cause victims to lose confidence and disengage.

The force’s crime recording isn’t of an acceptable standard to make sure victims get the right level of service

The force’s crime recording should be trustworthy. The force should be effective at recording reported crime in line with national standards and have effective systems and processes, which are supported by its leadership and culture.

The force needs to improve its crime recording processes to make sure all crimes reported to it are recorded correctly and without delay.

We set out more details about the force’s crime recording in the ‘crime data integrity’ section below.

The force allocates crimes to staff with suitable levels of experience, but doesn’t always inform victims if their crime won’t be investigated further

Police forces should have a policy to make sure crimes are allocated to trained officers or staff for investigation or, if appropriate, not investigated further. The policy should be applied consistently. The victim of the crime should be kept informed of who is dealing with their case and whether the crime is to be further investigated.

We found the force allocated recorded crimes for investigation according to its policy. In all cases, the crime was allocated to the right department for further investigation. But victims weren’t always updated to inform them that their crime report wouldn’t be investigated further. Doing this is important to give victims the right level of service and to manage their expectations.

Most investigations were effective and timely, but victims were sometimes not provided with the right level of advice and support for the crime

Police forces should investigate reported crimes quickly, proportionately and thoroughly. Victims should be kept updated about the investigation and the force should have effective governance arrangements to make sure investigation standards are high.

In most cases, the force carried out investigations in a timely way and completed relevant and proportionate lines of inquiry. Most investigations were reviewed by a supervisor, but not all investigations had an investigation plan. Victims were sometimes not updated throughout investigations. Victims are more likely to have confidence in a police investigation when they get regular updates.

A thorough investigation increases the likelihood of perpetrators being identified and a positive end result for the victim. Victim personal statements weren’t always taken. This can deprive victims of the opportunity to describe how that crime has affected their lives.

When victims withdrew support for an investigation, the force didn’t always consider progressing the case without the victim’s support. This can be an important method of safeguarding the victim and preventing further offences being committed. The force didn’t always consider the use of orders designed to protect victims, such as a domestic violence protection order (DVPO). The introduction of DVPO officers in basic command units (BCUs) has improved how the force uses these orders.

The Code of Practice for Victims of Crime requires forces to carry out a needs assessment at an early stage to determine whether victims need additional support. The outcome of the assessment and the request for additional support should be recorded. The force didn’t always complete a needs assessment. This can mean that victims don’t get the right level of service.

The force usually finalises reports of crime correctly

Forces should make sure it follows national guidance and rules for deciding the outcome of each report of crime. In deciding the outcome, forces should consider the nature of the crime, the offender and the victim. Leaders should support and oversee these decisions throughout the force. In some cases, offenders can receive a caution or community resolution. If these outcomes are to be used correctly, the offender’s previous history and the nature of the offence must be taken into account. The victim’s and the offender’s views should also be considered and recorded.

In most of the cases we reviewed involving a caution or community resolution, the offender met the national criteria for the use of these outcomes. But we found that the consideration of the victim’s wishes wasn’t always recorded.

At any point in an investigation when a suspect is identified but the victim doesn’t support police action, the force should make an auditable record of the victim’s decision. Evidence of the victim’s decision was missing in most cases we reviewed. The absence of any record of the victim’s wishes and decision to not support an investigation makes it difficult for the force to be certain it is considering what victims want.

Crime data integrity

The Metropolitan Police Service is adequate at recording crime.

We estimate that the force is recording 91.7 percent (with a confidence interval of +/- 2.4 percent) of all reported crime (excluding fraud). This is broadly unchanged compared with the findings from our 2018 inspection, when we found it recorded 89.5 percent (with a confidence interval of 1.6 percent) of all reported crime. We estimate that, compared to the findings of our 2018 inspection, the force recorded an additional 18,300 crimes for the year covered by our inspection. We estimate that the force didn’t record more than 69,100 crimes during the same period.

We estimate that the force is recording 86.4 percent (with a confidence interval of +/- 4.4 percent) of violent offences. This is broadly unchanged compared with the findings from our previous 2018 inspection, when we found it recorded 87.6 percent (with a confidence interval of +/- 2.8 percent) of violent offences.

We estimate that the force is recording 95.2 percent (with a confidence interval of +/- 3.7 percent) of sexual offences. This is broadly unchanged compared with the findings from our previous 2018 inspection, when we found it recorded 91 percent (with a confidence interval of +/- 2.9 percent) of sexual offences.

Main findings

In this section, we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force records crime.

The force needs to improve its recording of violent crime

The force isn’t always recording domestic abuse or behavioural crimes, such as controlling and coercive behaviour, stalking and harassment. Many victims of these crimes are victims of long-term abuse. It is important to record these crimes and meet the needs of victims, including safeguarding them.

The force has improved how it records rape offences

The force has improved how well it records rape offences, but not all reports of rape are correctly recorded. Rape is one of the most serious crimes a victim can experience. It is especially important that these crimes are recorded accurately to make sure victims receive the service and support they need.

The force records crimes against vulnerable people well

The force records crimes against vulnerable victims well. It is important that crimes against vulnerable people are recorded to help safeguard them from further offences and to identify perpetrators.

The force applies the correct standards when cancelling crimes

The force generally cancels crimes when it can be shown that no offence occurred, or that the crime was recorded in error. This makes sure that the force and the public have an accurate picture of what crime has taken place in their area.

Recording data about crime

The Metropolitan Police Service is adequate at recording crime.

Accurate crime recording is vital to providing a good service to the victims of crime. We inspected crime recording in London as part of our victim service assessments (VSAs). These track a victim’s journey from reporting a crime to the police, through to the outcome.

All forces are subject to a VSA within our PEEL inspection programme. In every other inspection forces will be assessed on their crime recording and given a separate grade.

You can see what we found in the ‘Providing a service to victims of crime’ section of this report.

Adequate

Engaging with and treating the public with fairness and respect

The Metropolitan Police Service is adequate at treating people fairly and with respect.

There remain tensions in the relationship between the force and some of its communities, specifically the Black community and other groups which have less contact with, or traditionally have lower trust and confidence in, the police.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to treating people fairly and with respect.

Public scrutiny of the force in the media

Police forces provide a public service. So it is right that there is public scrutiny of police activity and that this scrutiny is encouraged. The media plays a significant role in highlighting issues affecting the public. The MPS is the largest police force in the country, and is charged with protecting the capital city. This means it is constantly under public and media scrutiny. Some recent cases have generated prominent negative media coverage. Much of this attention is due to the behaviour of individual officers falling far below the standards of professional behaviour expected of British policing.

During this PEEL inspection and other recent inspections, we found many examples of police actions which reflect poorly, or will be seen by many as reflecting poorly, on the force. Examples of these include:

- aspects of the murder of, and subsequent vigil for, Sarah Everard;

- allegations of institutional corruption following the Daniel Morgan inquiry;

- the Independent Office for Police Conduct investigation into misogyny; and

- the stop and intimate search of some young female students.

Issues such as these have damaged public trust in the force. With negative reports featuring regularly in the media, it would be easy to label the force as failing in how it engages with the public. But, overall, this is not the case. We found many examples of police officers and staff working hard, professionally and with compassion in very difficult circumstances. We also found considerable evidence of fair treatment and inclusive engagement with the communities the force serves.

A dedicated command to close the trust gap between the police and the Black community

The force’s strategy for inclusion, diversity and engagement 2021–2025 is based on four main themes: protection, engagement, equality and learning. Its overriding aim is to keep London safe for everyone. The force has also created a dedicated command team (called ‘crime prevention, inclusion and engagement’) which is responsible for supporting internal and external partnerships. It aims to achieve a fully inclusive culture and a greater focus on preventing crime and engaging with diverse cultures.

The emphasis of the deputy commissioner’s delivery group is to close the ‘trust gap’ with London’s Black communities. It oversees the force’s activity against agreed actions in the Mayor’s Action Plan. Two of its four main aims are focused on the community:

- to improve trust, confidence and accountability for police encounters involving the exercise of powers or use of force in relation to Black communities; and

- to proactively engage with influential people outside the force who are critical of its approach to policing Black communities, and carry out specific engagement activity to encourage mutual listening and learning.

The force is also carrying out significant work on rebuilding trust with the public and creating an ethical and inclusive culture. It has introduced a rebuilding trust team, in response to the independent review of the force’s culture and standards of behaviour led by Baroness Casey of Blackstock DBE CB, and the national programme to tackle violence against women and girls.

The force is structured into 12 BCUs, which each have responsibility for a particular geographic area. It has produced a comprehensive BCU engagement plan that sets out the main areas of activity needed at BCU level to make sure engagement with communities “is focused, meaningful, relevant and authentic”.

The plan sets out 15 commitments for BCUs. These reflect the findings from a recent internal review of engagement and are aimed at supporting neighbourhood policing. The plan is in the early stages of implementation. We found that within BCUs there was already a comprehensive knowledge of community groups and other engagement opportunities. We look forward to seeing how BCUs turn this knowledge of their communities into engagement, and how this affects public confidence in the force.

Positive use of independent advisors

The force has several independent advisory groups (IAGs) which provide its own corporate groups (such as those focused on LGBT matters, race, and disability) and BCU-level groups with healthy and robust feedback on the perceptions of local communities. Quarterly meetings take place with all the IAGs, and productive discussions take place in which representatives voice the views of under-represented groups.

The force’s strategic advisory group (SAG) is a forum to help it understand the effects of its policies, improve engagement with diverse communities and influence structural change. The SAG comprises senior community leaders and representatives from youth and faith groups, education, academia and US law enforcement. It helps the force judge its responses to critical incidents and offers advice on high profile cases. Recently, it has given guidance on the diversity and inclusion strategy, the COVID-19 policing response and Black Lives Matter protests.

There are also many subgroups to the SAG. For example, strategic advisory cells involve SAG members being present in the force’s special operations room as ‘critical friends’. Here they offer support during community events such as festivals, memorial events and protests. This allows for productive two-way conversations. Force commanders can get guidance about the impact of the policing response. And the cell members can take their experiences back to their community to promote understanding of the force’s work.

The force works with its communities so it can understand and respond to what matters to them

The force actively seeks the views of its communities to identify local problems and gather intelligence. Every ward in London has a dedicated team comprised of police constables (PCs) and police community support officers (PCSOs). Separately, each BCU also has a team of PCSOs, who target high crime areas. Neighbourhood officers are deployed in areas of high violence and low trust in policing. We found that the various neighbourhood teams are generally effective. They actively engage with their communities, and most of their working time is spent dedicated to their ward.

We observed many positive community activities, including regular weekly ward meetings, that allowed the public to meet officers in person or virtually. There are dedicated schools officers with effective school engagement plans. And we found many examples of the force actively seeking views from other community workers including LGBT+ advisers, hate crime co-ordinators and local authority staff. In the South Central BCU at Lambeth, for example, the community team is building links with IAG members, youth groups and schools. Similarly, the South BCU engages effectively with the Croydon Voluntary Action, an umbrella group which includes 80 small local charities and community organisations.

It isn’t only BCU teams that involve communities in their work. We found examples of the territorial support group working with community groups, and the mounted section actively participating in community events as a way to break down barriers to communication.

The violent crime task force is actively working to involve communities in tackling violent crime. It has held discussions with local people on stop and search powers using role play and role reversal. And it has organised ‘ride-alongs’ for community members to join officers on patrol. The team encourages representation from all communities in its work. It has been actively encouraging the recruitment of young Black men to take part in the community reference panel (a discussion forum which gives local people the chance to voice any concerns they have).

The force recognises public engagement as a risk

While there is a significant amount of good work being carried out, we note that the force’s corporate risk register identifies public and local engagement as one of the long-term risks for the organisation. The force is seeking to understand why certain engagement activities are not increasing the community’s trust in it. In particular, the force recognises that it generally lacks the trust and confidence of the Black community.

Public attitude survey from the Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime

The Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime (MOPAC) publishes a ‘public voice dashboard’, focusing on public perceptions and victim satisfaction in relation to the force’s work. It allows the user to track performance over time, see data on the most important factors affecting public satisfaction, and understand the perceptions of crime victims and different demographic groups.

The data indicates a general decline in satisfaction levels since April 2020. Satisfaction with ‘Police actions’ fell from an estimated 66 percent in April to June 2020 to 59 percent in October to December 2021. In addition, ‘Ease of contact’ had fallen to an estimated 83 percent in October to December 2021 from an estimated 89 percent in April to June 2020. (We discuss problems with people contacting the force in the ‘Responding to the public’ section of this report.) The service area with the lowest levels of satisfaction was ‘Follow up’ (meaning updating victims about investigations). The survey shows that an estimated 55 percent of victims were happy with their treatment in January to March 2022.

Figures indicating trust and confidence in the force have fallen over the last two years. Trust levels have fallen from an estimated 83 percent in the year ending 31 March 2020 to an estimated 73 percent in the year ending 31 March 2022. Over the same period, the proportion of people who think the police is doing a ‘good job’ has fallen from an estimated 58 percent to an estimated 49 percent. Although this figure isn’t specifically measuring confidence, it is an indicator of public confidence. It can take longer to achieve an upward trajectory in this area, compared to user satisfaction.

The entire workforce has received training on unconscious bias

We found that the force has taken steps to make sure all staff have received unconscious bias training. This is important because it challenges individual perceptions to help officers treat the public fairly and without prejudice. Probationary constables all complete bias training. And promotion courses all include content on equality, diversity and inclusion and unconscious bias.

But the force needs to assure itself that its staff have a sound understanding of unconscious bias. We found that some staff were unclear about what it means, and even whether they had received training on it.

The force carries out the highest number of stop and searches in England and Wales

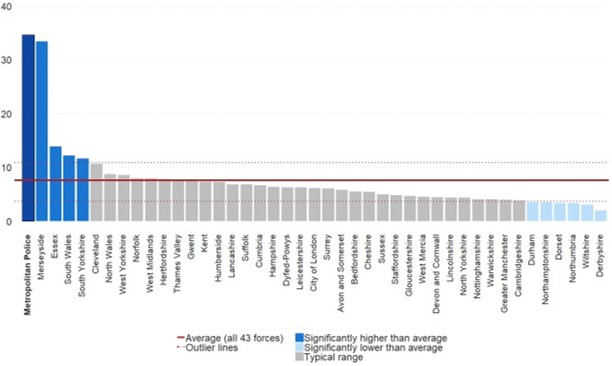

In the year ending 31 March 2021, the force carried out 316,747 stop and searches on persons and vehicles under all legislation. Of these, 311,295 were person stop and searches, representing 34.6 stop and searches per 1,000 population. This was significantly higher than the average of all forces in England and Wales of 7.6 per 1,000 population.

Person stop and searches per 1,000 population throughout forces in England and Wales in the year ending 31 March 2021

The force has strong governance to make sure stop and search is supervised effectively

The force uses internal scrutiny to help it understand its use of stop and search, and any disproportionality in relation to different demographics.

It has set up a monthly meeting for senior leaders to review stop and search performance and discuss any other matters relating to stop and search.

The continuous policing improvement command (CPIC) also holds a monthly meeting that makes sure there is oversight and accountability for stop and search. The stop and search leads for each borough attend this meeting. They are held accountable for stop searches in their area and report on data, outcomes, learning and community engagement relating to stop searches. The CPIC reviews all authorisations for stop searches under section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994.

The force recognises that the Black community and other under-represented groups generally do not trust it. It sees the use of stop and search as an important part of policing, and one that needs to be handled sensitively.

The force has a central stop and search team, which reports to a strategic lead and promotes the proportionate use of the tactic. The lead receives statistical information every two weeks from a dedicated analyst. At a local level, we found that daily ‘pacesetter’ management meetings in BCUs include stop and search data as an agenda item to help the units understand their use of stop searches.

BCUs follow a policy of transparency to encourage community understanding of how and why stop and search is used. For example, each borough has an active community monitoring group. These independent and rigorous external scrutiny panels are led by MOPAC and are making valuable contributions to making sure stop searches are used effectively.

We were told that supervision rates for stop and search had increased over the last two years. And we found that the supervision of stop and search was good. Supervisors in the CPIC regularly dip sample body-worn video footage. This is in addition to the dip samples that each BCU is required to carry out itself.

Through its website, the force makes positive efforts to demonstrate transparency in its use of stop and search. It publishes a comprehensive, user-friendly dashboard which includes data from the previous 24 months. The dashboard has multiple filter options to view data by categories such as gender, age, ethnicity, location, type of search and outcome.

Officers and staff are trained in stop and search and how to use force fairly and correctly

The force’s public personal safety training (PPST) has significantly changed over the last year. It now uses an ‘immersive pedagogic’ approach which encourages officers to consider the effects of their actions on an individual during an encounter.

The new PPST programme teaches officers not to use handcuffs without justification when searching passive people. In general, handcuffing is only justified if the officer has a reasonable belief that the person may cause harm to themselves, the officers or others, may attempt to impede the search or discard items, or may try to escape. The training balances both officer and public safety against the harm that unjustified handcuffing of passive people can do. Many officers we spoke to told us that this approach is ingrained into officers’ minds and followed.

From April 2022, the force is increasing PPST training time. There will be two days of PPST training and one day of emergency life support training per year for all frontline officers. It will introduce the new PPST curriculum in line with the timescales set by the College of Policing.

Adequate

Preventing crime and anti-social behaviour

The Metropolitan Police Service is good at prevention and deterrence.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to prevention and deterrence.

The force prioritises the prevention of crime, anti-social behaviour and vulnerability

The force’s priorities are clearly set out in its business plan and crime prevention strategy. There is robust and active oversight of crime prevention, both by senior leaders at a force-wide level and by BCUs through daily meetings. We found that officers understood the three strategic priorities of prevention, information and collaboration, and applied these in their local crime prevention initiatives. For example, we found examples of neighbourhood officers working with ‘designing out crime’ officers and the relevant local authority to reduce opportunities for crime in public spaces.

The force has reviewed how it involves communities in its work. Each BCU now has a clear community engagement strategy which includes scrutiny forums and working with schools. A ‘schools watch’ scheme, which involves dedicated officers being deployed in schools, is being implemented throughout all priority schools. The force has identified 263 priority schools based on crime levels and socio-economic data. Of these, 100 are already participating in the scheme. We found that recommendations in the community engagement strategies have been, and are continuing to be, implemented.

As discussed in the previous section of this report, the force has dedicated neighbourhood teams in each ward. In the BCUs we visited, we found that staff were working hard to build links with their communities and to widen the range of techniques they used to involve communities. These include increasing the use of social media and other online engagement, holding community events with partner organisations in harder to reach and under-represented areas, and adding a contact function for safer neighbourhood teams to the Police.uk web page.

In July 2021, the force’s strategic insight unit launched Operation Avert after consulting with BCUs. For this, it has identified 240 locations as having higher levels of crime, and is increasing the numbers of neighbourhood officers in these areas.

In addition, the violent crime taskforce is leading a force-wide project to reduce violence. The force has invested in new BCU violence suppression units to identify and target the most serious violent offenders, and patrol hotspot areas.

The force uses the SARA problem-solving model effectively with other organisations to prevent crime and anti-social behaviour

We found that the force had good problem-solving capabilities and had adopted the SARA model for its crime prevention strategy. SARA has been integrated as a template into the force’s IT systems. This allows officers to break down the steps of the problem-solving process and record their decisions for each stage. The model also forms part of the initial training given to all student police officers.

The force uses ‘designing out crime’ officers to reduce opportunities to commit crime. These officers work with local authorities in the planning stages of new development proposals – particularly those which relate to the night-time economy, nightclubs and late licences for bars. They currently certify 14,000 new homes a year to the police’s Secured by Design standards. We were told that the force’s evaluation showed that crime had reduced in most neighbourhoods where ‘designing out crime’ officers had been used.

We found problem-solving community initiatives in each of the BCUs we visited. One example is the ‘Walk and Talk’ initiative, developed in partnership with the local community following the murder of Sarah Everard. This involved officers walking with local women to discuss the issues that matter to them. It helps local officers to understand the experience of women and girls in the community, identify their concerns and develop a meaningful policing response to these.

We also found examples of imaginative community work with other organisations. This included schools officers working with the charity Elevated Minds to help run an early intervention programme. The programme involved mentoring vulnerable children, predominantly from ethnic minority backgrounds. It aimed to help them build emotional intelligence and develop self-awareness to reduce the risk of becoming a victim or a perpetrator of crime.

The force intends to increase the number of officers in neighbourhoods with the biggest crime and anti-social behaviour problems. To help achieve this, it is putting officers on duty at the right times in the right places, and developing effective relationships with other organisations. The force works hard to identify areas of high demand and vulnerable locations, groups and people. We saw that it has carried out modelling of neighbourhood wards and has identified 75 (of the total number of 650) that are at higher risk. In response, it has placed an extra 500 officers into town centre teams and an extra 150 into dedicated ward officer roles.

The force has introduced a centrally managed performance data pack which measures anti-social behaviour demand and how the force is responding to that demand. In addition, a neighbourhood performance data pack is produced monthly to give neighbourhood officers and supervisors information on anti-social behaviour, the anti-social behaviour early intervention scheme, community contact sessions and ward panel surveys.

Neighbourhood officers spend significant amounts of time policing their communities

We were pleased to see that neighbourhood officers were spending a significant amount of time in education and prevention initiatives working with young people. The force records time spent by neighbourhood officers in their wards, and BCUs monitor the amount of time that officers spend abstracted from this role to other tasks.

Abstraction levels away from neighbourhood functions were reasonable (‘abstraction’ means diversion to duties that aren’t part of the officer’s core duties, and not necessarily emergencies, for an extended period). We found that this was mainly being done to cover exceptional events such as national football matches, licensed festivals and national celebrations. Such events are planned for, and staff generally get sufficient notice to plan their time.

But we found that both response and neighbourhood officers were being diverted from community policing to deal with non-policing matters, particularly managing mental health issues. This is having a knock-on effect on the amount of time neighbourhood officers spend policing their community.

Good

Responding to the public

The Metropolitan Police Service is inadequate at responding to the public.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force responds to the public.

The force doesn’t always have the capacity to provide an effective and timely response to demand

The current MPS Command and Control Centre (MetCC) staffing model was based on 2013 demand. It was designed in 2014 based on an ‘80/20’ model. This means that 80 percent of the staff manage the day-to-day duty requirement and 20 percent of staff can be mobilised to work at times of peak demand. MetCC receives 6.3m contacts a year. This includes 1.8m ‘mentions’ on social media. It has identified 600,000 contacts as involving vulnerable people, with a mental health-related call every three minutes. An increase in demand now means that the 80 percent of staff managing the day-to-day duties can’t meet demand without overtime working. This is not sustainable.

On 31 May 2022, the Home Office published data on 999 call answering times. Call answering time is the time taken for a call to be transferred to a force, and the time taken by that force to answer it. In England and Wales, forces should aim to answer 90 percent of these calls within 10 seconds.

Since the Home Office hadn’t published this data at the time we made our judgment, we have used data provided by the force to assess how quickly it answers 999 calls.

The force acknowledges that it isn’t meeting the national thresholds for answering calls. It told us at the time of our inspection that 63.9 percent of 999 calls it received were answered within 10 seconds (the target is 90 percent) and that 36.6 percent of 101 calls were abandoned (the target is fewer than 10 percent).

The factors the force states are affecting timeliness include the capacity of call‑handling staff, increased complexity of calls, increased call volume and additional demand created by social media. We also found a consensus that the force was spending much of its time dealing with non-policing issues, especially during the pandemic.

The force fails to identify and understand risk effectively at the first point of contact

THRIVE+ is a model for assessing vulnerability risk consistently, from the point of first contact with the force to the closure of a crime report. Our victim service assessment found that the force didn’t use the THRIVE+ model consistently (in accordance with force policy) to make sure that incidents are accurately assessed. Only 21 of the 107 applicable incidents we reviewed had received a THRIVE+ assessment.

But we found that when THRIVE+ was used, it was an accurate reflection of the call in all 21 cases. Every officer we spoke to in frontline policing, or who was involved in call handling, told us that they had received relevant training, mostly through e-learning. The use of THRIVE+ was an area that we previously highlighted in the 2019 PEEL inspection as requiring improvement, and we are disappointed to see that the situation hasn’t improved.

MetCC monitors the use of THRIVE+ as a performance indicator. To do this, it carries out dip sampling on each shift of call handlers in each call centre. This sampling was described to us as “limited”, with Met CC supervisors dip sampling three calls per shift for compliance. We also heard that many supervisors don’t fully understand the THRIVE+ process. The force needs to assure itself that supervisors can highlight any areas of concern when dip sampling to monitor the use of THRIVE+, and respond accordingly.

The force is inconsistent in checking for victim vulnerability

While the evidence indicated that call handlers were usually considering vulnerability, this wasn’t being consistently recorded. In 54 out of 97 applicable cases we reviewed, the force carried out checks to identify vulnerability.

We also found that call handlers weren’t consistently carrying out checks to identify repeat victims. This was done in only 39 of the 96 applicable cases we reviewed. And when the right checks did take place and repeat victims were identified, they weren’t always recorded on the force’s systems. We found that 17 of the 27 cases involving repeat victims were recorded as required. This inconsistency means that callers who are repeat victims of crime may not receive a good service. The force may also not be taking every opportunity to reduce repeat victimisation.

The force provides the right response to incidents

We found that call handlers were polite and professional. The force grades calls correctly with the information the call handlers obtain. There is a consistent approach to allocating incidents to the workforce, and the right resources are deployed. Response times are within the force’s targets and there is a proportionate use of the appointment system.

The force needs to make sure that call handlers give good advice on the preservation of evidence and crime prevention

The force has a detailed guidance document to help call handlers give advice on how to preserve potential evidence. But our victim service assessment found that callers weren’t always being given appropriate advice on preserving evidence. Scene preservation advice was given in only 15 out of 35 cases we reviewed where this would have been appropriate. And crime prevention advice wasn’t always provided either. Advice on preventing crime was given to callers in only 31 out of 43 cases we reviewed.

This means that the force is missing opportunities to preserve evidence which may help investigations. And in some cases, it is failing to give victims advice to prevent further crime, which could reduce repeat victimisation.

The force is providing professional development on first point of contact and emergency response policing

MetCC aspires to have a fully multi-competent workforce, where staff are able to switch between different roles within the centre. This would create the flexibility it needs to meet fluctuating demand. We found that many staff already have additional skills to support this model, and that training is planned to give all the centre’s workforce the right skills. MetCC has its own training academy, which has recently invested in an accreditation scheme to support continuous professional development. The academy has benchmarked all professional development modules to approved standards. This means the workforce can get nationally recognised management qualifications.

The force needs to understand and plan for the increasing demand facing MetCC

The growth forecast for MetCC suggests that demand will continue to increase over the next few years. The factors affecting demand include new online reporting tools, the time needed to record crimes during calls and additional vulnerability assessment processes. The force stated that unless the MetCC model is transformed, within 3 years up to 50 percent of demand may not be met. In the short term, the force will manage demand by increasing the budget for MetCC to fund overtime, recruitment and training.

In the longer term, the force is relying on a planned new IT system to increase efficiency and reduce demand for MetCC. The system is scheduled to be implemented after the implementation of the CONNECT IT programme, which will integrate many of the force’s IT systems. Both programmes are delayed.

Inadequate

Investigating crime

The Metropolitan Police Service requires improvement at investigating crime.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force investigates crime.

The quality of crime investigation is improving

In 2019, we said that the force needed to improve the quality of its investigations. It had to improve its assessment of risk, make sure crimes were investigated by the right people with the right skills, improve digital forensics and increase the capability and capacity of investigators. In this inspection, we found that the force has invested time and money into developing its investigative capacity and improving crime allocation. But we found that there was only a slight improvement in both risk assessment and digital forensics. We want to see further improvements in these areas.

We note that the force is focusing on three main improvement themes: the use of THRIVE+, maximising investigative interviewing skills, and the efficient and effective use of digital evidence.

The force has a policy for most areas of crime investigation, including general investigation policies and specific policies for individual crime types. Due to finite numbers of investigators, the force can’t investigate each reported crime to the same standard. It uses THRIVE+ and the Crime Assessment Principles to improve the quality of its decision-making for investigations on the basis of risk, vulnerability and potential solvability.

THRIVE+ is widely used in investigations, but often without an understanding of its purpose

THRIVE+ is used in all investigations from the point of first contact with the force. Most investigators we spoke to considered THRIVE+ to be more of a bureaucratic exercise than a tool to genuinely assess risk and vulnerability. We found that the quality of assessments was mixed. The force needs to improve investigators’ understanding of the purpose of THRIVE+ and make sure it informs all investigations.

Crime allocation is consistent, and crimes are generally investigated by the right teams

In this inspection, we found that investigations were generally effective. Our victim service assessment found that investigations were allocated to the right teams and in accordance with the crime allocation policy in almost all (100 of 105) the cases we reviewed. Arrests were made at the earliest opportunity in 24 of 26 relevant cases we reviewed.

The force has a policy that identifies eight serious and complex case types that should be assigned to its criminal investigation department. If it isn’t one of these case types, an investigation stays with investigators within response teams. BCUs can direct crimes to be investigated by particular teams based on local priorities. This means that BCUs can allocate crimes to teams with the capacity to investigate them. But we found that in order to do this, ad hoc units were sometimes being created outside of the force’s operating model. This often reduced officer numbers in frontline policing roles. BCUs should assess any changes like this against the force’s operating model to judge their overall efficiency and effectiveness.

The force recognises the importance of forensic evidence and is investing to meet future demand for forensic examination

The force is investing in improving forensic services to support investigations. This includes additional forensic kiosks to transfer digital evidence from devices. There is a programme aimed at improving the retention of forensic staff. This includes improved conditions, including more development opportunities, and better welfare support to deal with trauma.

The force has processes to manage its investigations demand

Demand is monitored daily through ‘pacesetter’ meetings in BCUs. This is supported by accurate data that is published weekly and scrutinised at the monthly frontline policing crime board. Force-wide performance is monitored at the force strategic performance board, which is chaired by the deputy commissioner.

Each BCU has its own weekly performance data pack, containing information on crime and the successful conclusion of investigations. We found that all the key performance indicators within this showed substantial improvement since our last inspection, with the notable exception of victim satisfaction.

The force has effective governance to improve the quality of investigations

There is an investigations improvement plan, which sets out clear actions to improve all aspects of investigations. Senior leaders oversee the plan’s implementation. This has led to an increase in the number of detectives in frontline policing investigations. But there is a lack of experience and skills among newer detectives, who tend to have large caseloads. Local policing teams have the highest numbers of inexperienced investigators. The force needs to increase skill levels and reduce caseloads.

The force recognises that it lacks investigative capacity. Its operating model set staffing levels in 2019, but demand has substantially increased since then. The force needs to review its operating model to make sure staffing levels can meet demand.

To help increase the number of detectives, the force offers a personal tutoring programme to help suitable candidates to pass the National Investigators’ Exam. It gives them mentors, digital study aids, virtual seminars and classroom lessons. They can then complete mock exams. The force told us this has resulted in an increase in the pass rate by 18 percent.

The improvement plan has led to generally better investigations and to increased numbers of investigators in the force. But the force’s ongoing improvement is dependent on implementing the CONNECT IT programme. The reliance on IT upgrades is a concern to us, as many of the planned IT upgrade programmes have already experienced delays.

The supervision of investigations isn’t always effective

The force has policies for the supervision of investigations. We found that the high proportion of inexperienced staff and a lack of experienced tutors for detectives meant that supervisors were often teaching staff how to investigate crime rather than supervising them. And not all investigations had supervisor reviews. We found that good supervisors created good investigative plans. And investigations with both good supervision and well drafted plans led to better outcomes for victims.

Requires improvement

Protecting vulnerable people

The Metropolitan Police Service requires improvement at protecting vulnerable people.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force protects vulnerable people.

The force’s governance of its service to vulnerable people is disjointed

We found that there was strong strategic oversight of the public protection portfolio. The force has created a public protection improvement plan which covers each of the twelve categories of vulnerability, as set out in the National Vulnerability Action Plan. Each of the categories has a lead senior officer. And areas such as rape and serious sexual offences (RASSO), child protection and domestic abuse have full-time leads.

There has been good progress in providing training to child protection investigators and there is a programme to train the remainder who haven’t yet received this.

But there is a lack of cohesion between the people responsible for the governance of the improvement plan and those responsible for the staff implementing it. The plan is being implemented by staff within the frontline policing command, who are given different performance targets to those set out in the plan. We found that this was creating tension for public protection leaders, who were having to balance the expectations both of local leaders and of corporate strategic leads.

In addition, there remains a strong focus on criminal justice outcomes as an end in itself, rather than on achieving the best outcome for victims. The priority should be the safety and wellbeing of a victim.

Our inspection recognised that senior leaders and staff working within public protection investigation teams want to respond well to keeping vulnerable people safe.

The force doesn’t always have enough capacity to meet the needs of vulnerable victims

Staff and supervisors in units dedicated to dealing with vulnerable victims, such as domestic abuse investigation teams, told us that their caseloads were often unmanageable. We found that overtime was being used routinely to keep up with demand. And there was evidence of staff working on rest days to complete tasks.

We found that public protection teams had the least experienced staff of all the force – mostly people still in their initial detective training period. The force appears to see public protection as a role that anyone can perform, and one everyone should gain experience of early in their investigative career. We found that roles in public protection aren’t valued for their high levels of risk management or for the nuances of dealing with the most vulnerable victims. Experienced staff are generally quick to leave them. And public protection leaders are powerless to stop them leaving, despite the overwhelming demand they face.

The force contributes to the effectiveness of multi-agency risk assessment conferences

The force’s participation in multi-agency risk assessment conferences (MARACs) is well established. MARACs are held in each local authority area covered by the force. At the conferences we observed, we found good attendance and participation from statutory and non-statutory bodies (including social services, children’s services, housing and health organisations, and independent advisors on domestic and sexual violence). The meetings included active information sharing and activities to support the safeguarding of victims and families. The chair made sure that actions were recorded and tracked in the minutes. We found that the MARACs were constructive and resulted in plans that increased the safety of the victims discussed.

Dedicated officers support the use of domestic violence protection orders

Domestic violence protection order (DVPO) officers in each BCU assess all domestic violence cases every morning. They then give advice on whether an application for a DVPO should be considered. And they give expert support to investigators throughout the application process. This has led to the increased use of these orders, and an improved understanding about them within public protection teams.

The management of online child abuse is a reducing risk for the force

In previous inspections, we have found large backlogs in processing online child abuse cases. The force uses a central team and local teams in combination to manage the investigation of online child abuse. It has developed a prioritisation process to make sure that cases involving the highest risk of ongoing abuse of children are dealt with by specialist trained staff. The backlog of cases has been steadily declining, from 1,300 in October 2021 to 329 in June 2022.

Requires improvement

Managing offenders and suspects

The Metropolitan Police Service requires improvement at managing offenders and suspects.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force manages offenders and suspects.

The force uses recognised risk assessment tools and dedicated investigation teams to manage registered sex offenders and violent offenders

We found that the force is using approved risk assessment tools for managing sex offenders and violent offenders. It uses these to create good, well-structured risk management plans for the continual management of offenders.

The Jigsaw teams actively work with neighbourhood policing teams to help with managing offenders. They share intelligence where possible, and neighbourhood staff actively seek to fill intelligence gaps.

The force should review its policy of removing experienced staff from Jigsaw and online child abuse and exploitation teams

The force has a policy of removing detectives from the Jigsaw and online child sexual abuse and exploitation teams, to increase investigation capacity elsewhere. But we found that there was a shortage of experienced officers in both of these teams. The time and cost taken to train people as specialists and then move them elsewhere in the department may be justified. But it may also be an inefficient use of their skills.

The force uses software to effectively manage sex offenders’ use of digital technology

The force installs ESAFE software on sex offenders’ computers to monitor their use. It also uses this software to monitor offenders subject to sexual harm prevention orders with conditions that restrict their access to harmful material. This allows officers to detect any further offences and to accurately assess the risk a person poses. This can be done while visiting the home address of a registered sex offender using portable triage equipment.

Requires improvement

Disrupting serious organised crime

The Metropolitan Police Service is adequate at tackling serious and organised crime (SOC).

Understanding SOC and setting priorities to tackle it

The MPS has a large intelligence gathering capability to assess the threat from organised crime. It produces a control strategy to help the force prioritise the targeting of organised crime threats.

However, we found several areas where the collection of intelligence and information wasn’t as effective as it should be. This means that the force doesn’t always have the best information available to assess the threat and risk from organised crime.

Resources and skills

The economic crime teams can’t meet SOC demand

We have outlined that the economic crime teams have significant resourcing pressures. This means that they can’t meet demand and are missing some opportunities to identify and confiscate criminal assets. Furthermore, the force is potentially losing out on extra funds from selling criminal assets, through the Home Office asset recovery incentivisation scheme.

Financial investigators told us that they had insufficient time to fully investigate all suspects in their assigned cases. In one example, 30 suspects had been arrested for drug supply. The appointed financial investigator could only concentrate on the four top suspects. Because of this, investigators weren’t able to establish whether the other 26 suspects had any criminal assets. In another case, officers identified that at least £7.5m had passed through the bank accounts of an OCG. However, the lack of available financial investigators meant the origin of this money was never investigated.

Officers from Trident teams – the MPS teams that investigate non-fatal shootings – told us that they had stopped asking for financial investigator support because generally none was available.

The MPS has invested in the provision of digital forensics

The MPS has invested in personnel and technology to improve how it investigates crimes involving digital evidence. This includes a new IT system for analysing data recovered from mobile phones, which one investigator described as a “game changer”. We heard from investigators that they had access to good levels of equipment and to trained officers to analyse mobile phones and other digital devices in support of their organised crime investigations.

The use of organised crime advisors has improved how SOC is tackled

The MPS has trained organised crime advisors. These are qualified detectives who can assist with problem-solving and understanding the specialist tactics and resources available to support organised crime investigations. Frontline personnel have welcomed this initiative.

Tackling SOC and safeguarding people and communities

The MPS supports local and national initiatives to tackle SOC

The Home Office has provided the MPS with additional funding to lead national initiatives aimed at tackling SOC. For example, the force led Operation Orochi, working with other forces to tackle county lines drug supply. The force told us that, so far, they have closed 952 telephone lines operated by drug dealers and made over 2,000 arrests. Since 1 April 2022, further Home Office funding has been obtained to expand Operation Orochi to fund a drug task force to dismantle SOC networks across London. Another project supported by funding has seen hundreds of harmful posts removed from the internet. This project also provides key social media intelligence and evidential support to SOC investigations.

The MPS is successful at targeting and disrupting organised crime

We found examples of how the force had successfully targeted and disrupted organised criminals:

- An operation used a wide range of tactics to target three female drug couriers suspected of exporting cocaine to Australia. This resulted in the seizure of large amounts of cash and cocaine, as well as the arrest of the main members of the OCG.

- A large-scale human trafficking operation identified and safeguarded over 300 individuals and disrupted the OCG that had been exploiting them.

- Since 2018, a project to disrupt OCGs has resulted in 261 vehicles, 743 kg of drugs and 15 firearms being confiscated, and £2.4m in cash being recovered. At the time of our inspection, the number of people charged with a drug trafficking offence had risen by 31 percent to 6,784, compared to the previous 12‑month period.

The MPS has improved how it records disruptions of OCGs

The MPS has made substantial improvements in the way that it records disruptions of OCGs. In the year ending 30 June 2022, the number of disruptions recorded rose from 4,795 to 8,021. Of these, 78 percent were pursue disruptions, 10 percent were protect disruptions, 7 percent were prevent disruptions and 5 percent were prepare disruptions. However, the force acknowledges further work remains to be done. Most personnel we spoke to understood what was expected of them concerning the reporting of disruptions.

This improvement appears to be due to positive leadership from the deputy assistant commissioner and other senior officers to refocus the workforce on recording disruptions.

The MPS is improving operational support for covert teams

During our inspection, we were told that the operation support rooms in the force could monitor only a limited number of covert operational teams. However, the force has many more covert operational teams, meaning it is likely that at times this support may not be sufficient. In one example we were told of, a firearms commander had to use his personal device to monitor the locations of his teams on a live operation.

The force is working to expand its operational support facilities to allow support for more covert operational teams, so that their activity can be fully and securely monitored and deployed officers kept safe. We welcome these changes.

Safeguarding procedures are generally understood by personnel

Most personnel we spoke to appeared to understand safeguarding procedures and how to access support when required. We found good evidence of safeguarding in crime types such as county lines drug dealing and modern slavery.

Partnership structures appear inconsistent

During our inspection, we found an inconsistent picture of partnership working.

Some areas in the force have well-established partnership arrangements and we saw evidence of effective preventative initiatives being led by partners. These include the Most Valuable Person programme and the Constructive Conversation Programme. Both are aimed primarily at high-harm gang members and are designed to help them make better life choices. Also involved in trying to divert individuals away from the influence of organised crime and county lines drug supply are Project Adder and the Rescue & Response Partnership (including St Giles Trust, Abianda and Safer London).

But in other areas we found little evidence of working with partners to divert people away from organised crime. In 3 of the 12 BCUs, there is an integrated gangs unit, which appears to work well with partners such as youth services. The force should consider replicating this unit to improve partnership working in all BCUs.

The MPS should look to bring consistency to partnership structures and intelligence sharing. It should support this with 4P plans across all organised crime investigations, not just those involving high-harm gangs, county lines or drug supply.

The cybercrime team has developed several initiatives to prevent people from becoming victims of crime

The cybercrime team has visited all 3,200 schools across London and provided a basic cyber awareness package. Additionally, 580 people have signed up for cyber awareness webinars. The team has conducted over 130 presentations to individuals and groups, highlighting the threat from cybercrime.

Read An inspection of the London regional response to serious and organised crime – May 2023

Adequate

Building, supporting and protecting the workforce

The Metropolitan Police Service requires improvement at building and developing its workforce.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force builds and develops its workforce.

The force is aware of the need to rebuild trust with the community, and is investing in this work

The force recently introduced a rebuilding trust team. This was in response to many high-profile incidents that have damaged the reputation of the force and its relationship with the community. The team’s work is being overseen by a senior leader to make sure that its importance is understood and to provide impetus throughout the organisation. Several of the work programmes aim to improve standards of behaviour in the workforce. The force will clearly set out and communicate its expectations to promote a professional, ethical and inclusive culture.

The force’s efforts to support staff wellbeing are being undermined by high workloads, poor training and poor supervision

Staff generally feel supported by their managers, and feel that managers genuinely care about their welfare. The force has extensive occupational health services and continues to invest in these. There are also local arrangements in place in BCUs for informal wellbeing support. These include organised activities such as exercise classes, and set times when managers are available to chat.

But we found that many frontline policing staff felt too busy to use the available occupational health or informal wellbeing services. Some told us that they didn’t tell their supervisors about how they felt at work because their supervisors couldn’t reduce the pressure from their overwhelming workloads. Other factors negatively affecting wellbeing include the poor training and supervision covered in other sections of this report.

The force has a good process for monitoring personnel assaulted during their duty. Operation Hampshire is its programme for notifying management teams of any assaults on their staff so they can arrange any necessary support.

Staff generally felt that occupational health services had improved recently. But waiting times have increased. The average waiting time for a worker to receive an appointment increased from 7 days in January to March 2020, to 11 days in January to March 2021, and 12 days in January to March 2022.

Psychological screening is in place for certain high-risk roles, such as those which involve viewing indecent images of children. Screening should happen every 6 months, but some staff aren’t receiving assessments for 18 months.

The health, safety and wellbeing board is now responsible for the governance of health, safety and wellbeing. This board has only recently taken on responsibility for wellbeing, so it wasn’t possible to assess the impact of its oversight at the time of our inspection.

The force has an effective plan to recruit new staff, but it also needs to focus on retaining existing staff

The force understands its recruitment needs and is recruiting large numbers of new officers as part of the Police Uplift Programme. It has a target of recruiting 4,557 additional officers by March 2023. By 31 December 2021, it had recruited 78 percent of its allocation for the first two years of the programme (to 31 March 2022).

This recruitment drive is creating an inexperienced workforce. All frontline policing teams are facing similar problems. New, inexperienced staff with limited practical experience are being managed by similarly inexperienced supervisors trying to balance supervision with providing basic training. Opportunities for staff to learn from experienced officers are being lost as many staff join specialist units soon after they finish their probationary period.

Around 1,500 officers are leaving the force every year, in part due to high workloads and poor supervision. Attrition rates this high undermine the force’s success in recruitment. Investment in staff retention is more cost-effective than training new recruits.

The force is taking effective action so that its workforce better reflects its communities

The force has a clear plan to recruit a workforce that better reflects the community. Its inclusion and diversity strategy sets out projects which should help to achieve greater diversity. There is a policy of taking positive action to recruit officers and staff from under-represented communities. And the force has a dedicated outreach team, who attend local events to engage with under-represented communities. The force told us that more than 4,000 people have registered interest in joining it as police officers following contact with outreach staff. Of these, over 50 percent were from ethnic minority backgrounds and over 40 percent were female. The force provides support through the application process, with applicants given a named caseworker. There is also a ‘buddy’ scheme for all new recruits from ethnic minority backgrounds, to give support during periods of training where previously recruits tended to drop out.

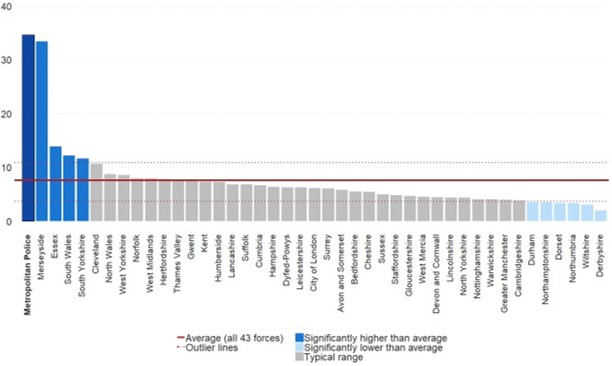

On 31 March 2021, 19.2 percent of the force’s workforce who stated their ethnicity were from an ethnic minority background. This was the highest proportion of all forces in England and Wales, in which the average figure is 7.8 percent. But the 2011 Census estimates that 40.2 percent of the population of London is from an ethnic minority background, so there is still some way to go for the force to be truly representative of its community.

Proportion of the workforce (that stated their ethnicity) from an ethnic minority background across all forces as at 31 March 2021

Vetting and counter corruption

We now inspect how forces deal with vetting and counter corruption differently. This is so we can be more effective and efficient in how we inspect this high-risk area of police business.

Corruption in forces is tackled by specialist units, designed to proactively target corruption threats. Police corruption is corrosive and poses a significant risk to public trust and confidence. There is a national expectation of standards and how they should use specialist resources and assets to target and arrest those that pose the highest threat.

Through our new inspections, we seek to understand how well forces apply these standards. As a result, we now inspect forces and report on national risks and performance in this area. We now grade and report on forces’ performance separately.

The Metropolitan Police Service’s vetting and counter corruption inspection hasn’t yet been completed. We will update our website with our findings and the separate report once the inspection is complete.

We have, however, recently carried out an inspection of the MPS counter-corruption arrangements and other matters relating to the Daniel Morgan Independent Panel. The force received five causes of concern in this report.

Requires improvement

Strategic planning, organisational management and value for money

The Metropolitan Police Service requires improvement at operating efficiently.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force operates efficiently.

The force actively seeks opportunities to improve services through collaboration with other agencies

The force collaborates well with other organisations in some areas of its work. This includes sharing some firearms officers with the counter terrorism network. The force has formal arrangements to work closely with Transport for London, City of London Police and British Transport Police. And it has developed operational protocols with other forces to manage cross-border work such as county lines drug dealing.

The force also focuses its collaboration efforts on aspects of its work where its resources are often used to respond to incidents despite not being the primary responsible agency. One example of successful collaboration is in the context of mental health. The force has formed crisis attendance teams who jointly patrol with mental health practitioners, to provide better care and reduce the burden on police staff.

The force makes the best use of the finance it has available, and its plans are both ambitious and sustainable

The force has robust financial management in place. MOPAC and the force are audited jointly by external auditors. These have consistently found that the force has good processes in place to make sure it manages its finances with “economy, efficiency and effectiveness”.

The force has an ambitious transformation programme whose stated aims prioritise work that benefits the public first and the force second. The transformation portfolio manages 14 improvement programmes, comprising 80 individual projects. There is a clear governance structure connecting the transformation work to all areas of work, and a review programme to make sure the stated benefits are achieved. Projects range from making the estate more efficient (getting more people into less space) to increasing the numbers and capability of police officers.

The force produces extensive data showing crime trends and its performance in tackling them

The force and MOPAC produce regular and accessible data allowing the public to understand the issues facing their community. Internally, the force provides clear data dashboards for each area of its work, including partnerships with local organisations. We found that the use of this data varies between teams, depending on the leadership’s capacity and capability at understanding data. Some BCUs use the data dashboards to effectively prioritise work and move staff to meet changes in demand.

There are good examples of the force working in partnership with other organisations to provide better services to the public. The force shares local data with other agencies. But there was little evidence that the shared data is then used to make decisions about partnership priorities. We found that information about vulnerability is shared with safeguarding partners, for example. But this didn’t lead to planning joint activity.

Requires improvement

About the data

Data in this report is from a range of sources, including:

- Home Office;

- Office for National Statistics (ONS);

- our inspection fieldwork; and

- data we collected directly from all 43 police forces in England and Wales.