Overall summary

Our judgments

Our inspection assessed how good Durham Constabulary is in 12 areas of policing. We make graded judgments in 10 of these 12 areas, as follows:

We also inspected how well Durham Constabulary meets its obligations under the strategic policing requirement, and how well it protects the public from armed threats. We do not make graded judgments in these areas.

We set out our detailed findings about things the force is doing well and where the force should improve in the rest of this report.

Important changes to PEEL

In 2014, we introduced our police effectiveness, efficiency and legitimacy (PEEL) inspections, which assess the performance of all 43 police forces in England and Wales. Since then, we have been continuously adapting our approach and this year has seen the most significant changes yet.

We are moving to a more intelligence-led, continual assessment approach, rather than the annual PEEL inspections we used in previous years. For instance, we have integrated our rolling crime data integrity inspections into these PEEL assessments. Our PEEL victim service assessment will now include a crime data integrity element in at least every other assessment. We have also changed our approach to graded judgments. We now assess forces against the characteristics of good performance, and we more clearly link our judgments to causes of concern and areas for improvement. We have also expanded our previous four-tier system of judgments to five tiers. As a result, we can state more precisely where we consider improvement is needed and highlight more effectively the best ways of doing things.

However, these changes mean that it isn’t possible to make direct comparisons between the grades awarded this year with those from previous PEEL inspections. A reduction in grade, particularly from good to adequate, does not necessarily mean that there has been a reduction in performance, unless we say so in the report.

HM Inspector’s observations

“I congratulate Durham Constabulary on its overall good performance in keeping people safe and reducing crime, although it needs to improve in some areas to provide a consistently good service.

These are the findings I consider most important from our assessment of the force over the past year.

The force’s serious and organised crime disruption team, and the extremely effective partnerships with other organisations, reduce the threat from serious and organised crime

I am impressed by the well-established approach to disrupting the threat posed by serious and organised crime. The dedicated disruption team is supported by a very effective partnership disruption panel. Intelligence is shared allowing an effective approach to managing serious and organised crime, focused on prevention and deterrence.

The force moved quickly to change police staff contracts, taking advantage of the benefits of home working and making best use of its finances

The force identified long-term benefits for the organisation and its staff from enforced home working during the pandemic. It moved quickly to amend police staff contracts to seal in those benefits.

The force has an effective and innovative integrated offender management programme

The force works hard to break the cycle of repeated offending. It is willing to try new ideas and I was pleased to see the success of the Checkpoint programme. Offenders have been encouraged to turn their lives around by addressing the causes of their offending.

An independent panel scrutinises arrests of people from black, Asian or minority ethnic (BAME) backgrounds, and the constabulary’s use of force and stop and search

Established with the police and crime commissioner, the panel is diverse and representative. It provides independent assurance on the arrest of people from a BAME background; the use of stop and search; and the use of force.

The force promotes an ethical and inclusive culture, and equips supervisors with leadership, wellbeing and inclusion training

All supervisors attend a five-day leadership, wellbeing and inclusion course. Designed by leading professionals and academics, participants examine the importance of values and what drives behaviour. I am encouraged to hear how participants have since put this learning to practical benefit in the workplace, improving their own leadership.

The force should improve its compliance with the requirements of the Code of Practice for Victims

Introduced in 2006 and amended as recently as April 2021, the Code sets out 12 rights that victims can expect from the criminal justice system. While the force has provided training to staff, work is needed to ensure that it is applied more consistently – in particular, by ensuring that it identifies and meets the needs of individual victims.

My report now sets out the fuller findings of this inspection. While I congratulate the officers and staff of Durham Constabulary for their efforts in keeping the public safe, I will monitor the progress towards addressing the areas I have identified, where the force can improve further.”

Andy Cooke

HM Inspector of Constabulary

Performance in context

As part of our continuous assessment of police forces, we analyse a range of data to explore performance across all aspects of policing. In this section, we present the data and analysis that best illustrate the most important findings from our assessment of the force over the past year. For more information on this data and analysis, please select the ‘About the data’ section below.

Compared with the rate across all England and Wales forces, Durham Constabulary has higher rates of domestic abuse-related crime. Durham Constabulary identifies a higher proportion of victims of domestic abuse that are repeat victims.

Domestic abuse crimes and repeat crimes per 1,000 population

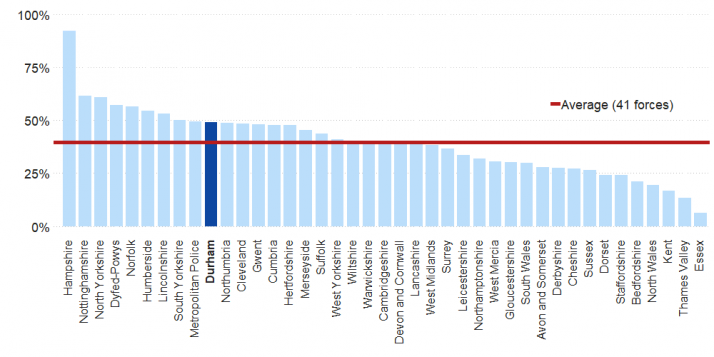

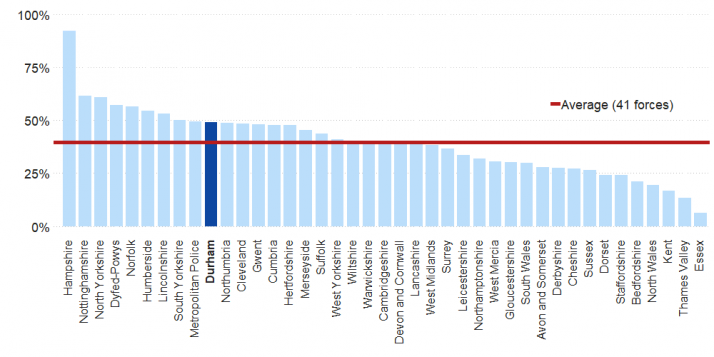

Our inspection found that Durham Constabulary had policies in place that enabled police to alert victims of domestic abuse of their rights, as provided for in the domestic violence disclosure scheme (Clare’s Law). The force is above the average across all England and Wales forces for responding to victims’ requests for information about potential abusers (right to ask).

Ratio of disclosures to applications for Clare’s Law (right to ask) for year ending 30 September 2020

Providing a service to the victims of crime

Durham Constabulary is adequate at providing a service for victims of crime.

Main findings

In this section, we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force provides a service to victims of crime.

The force manages incoming calls, assesses risk and prioritises its response well

Durham Constabulary consistently meets the national target for answering 999 calls (90 percent within 10 seconds). And it consistently answers 101 calls promptly. This is good because it means that the force generally answers calls from the public quickly, allowing a response in good time. It also means that fewer calls are abandoned.

Call handlers routinely apply a structured approach, using THRIVE, to risk assess calls from the public. This assessment is recorded on the incident log and used to make appropriate prioritisation and deployment decisions. Call handlers are good at identifying repeat callers and those who are vulnerable.

Call handlers are invariably polite and professional, and show empathy. They offer good advice on crime prevention and preserving evidence when appropriate.

The force deploys its resources to respond to victims and incidents appropriately

The force usually responds to incidents quickly and with the appropriate resources. It often uses an appointment system to attend when it suits the victim.

The force has effective arrangements for screening and allocating crimes for further investigation. These take vulnerability and risk into account

The force has a system to ensure that reported crimes are recorded promptly. This includes reviewing incidents flagged as anti-social behaviour and domestic abuse to identify and record crimes within 24 hours. The force does not have a written policy on allocating crimes for further investigation. Instead, it relies on supervisors allocating all crimes based on the levels of threat, harm, risk and complexity. We found that this approach worked well, and crimes were usually allocated to the most appropriate resource.

The force carries out proportionate, thorough and prompt investigations into reported crimes

We reviewed a sample of 70 crime investigations. We concluded that 58 of these had been investigated effectively. In 60, we found that the investigation had been conducted promptly. In almost all (64), there had been a proportionate investigation with appropriate lines of enquiry. The standard of victim care and engagement was satisfactory in 60 of these cases.

Good investigations often benefit from effective supervisory oversight, including setting a structured plan. We concluded that almost a third of cases lacked effective supervision. Of the 43 cases where we would have expected to find an investigation plan, they were present in just over half (23). The force should improve the level of supervision, and the quality and consistency of its investigative plans.

The force could do more to make sure that it follows national guidance for deciding the outcome it gives for each crime reported

Our review found evidence of good victim care and appropriate results for the victim in 56 of the 68 concluded cases. There are various reasons why some victims of crime may not want to pursue cases to a formal conclusion. In some cases, it could be appropriate for the police to prosecute an offender based on the available evidence. We found 17 such cases in the ones we reviewed and were disappointed that the force had pursued a prosecution in only 5 of them. The force could do more to secure justice in such cases.

Adequate

Engaging with and treating the public with fairness and respect

Durham Constabulary is good at treating people fairly and with respect.

Main findings

In this section, we set out our main findings that relate to treating people fairly and with respect.

The force engages with all its diverse communities to understand and respond to what matters to them

The force understands the diverse communities that it serves. It uses ‘Keep In The Know’, a two-way messaging system between the force and the public. It also holds regular Police and Communities Together (PACT) meetings to identify local priorities and concerns. During the coronavirus pandemic, PACT meetings were held online, with the force communicating with over 26,000 residents.

The workforce understands how to treat the public with fairness and respect, and why it is important

The chief constable has set out her values for the force. These are positive; fair; courageous; inclusive; and with integrity. All staff recognise and understand these values. They are reinforced through personal safety training for police officers. The training emphasises:

The workforce understands how to use stop and search powers fairly and respectfully

All police officers have had initial training in using stop and search powers. This is refreshed in the annual personal safety training. The force requires stop and search encounters to be video recorded on body-worn devices. We reviewed 123 stop and search records. We concluded that moderate or strong reasonable grounds were evident in 110 (89 percent) of these cases. This is broadly consistent with the positive findings in our previous audits.

The force understands and improves the way it uses stop and search powers

The force has an established internal scrutiny process, which it uses to understand and monitor its use of stop and search. Comprehensive information and data on stop and search are available through an online system. This includes a dashboard that includes easy-to-access information on a range of factors such as age, gender and ethnicity. The force monitors which officers carry out the most searches and reviews the data for any sign of disproportionality. The BUS Panel provides external, independent scrutiny and challenge.

The workforce understands how to use force fairly and appropriately

All student officers have tuition in personal safety, tactical communication and the use of force as part of their initial training. All officers must then complete annual personal safety refresher training. During the pandemic, refresher training was reduced from one day to half a day and the focus was on mandatory certification requirements. The force has recently extended personal safety training to two days. The training includes lessons on legitimacy and proportionality. Officers are tested on their knowledge and operational competence.

The force understands, and improves, its use of force

The force monitors its use of force in a similar way to its use of stop and search. Supervisors have access to information via a dashboard. Internal scrutiny also includes staff from the professional standards department and personal safety trainers dip sampling incidents where force is used. This identifies any potential disproportionality, as well as highlighting any individual or organisational problems. The BUS Panel provides external, independent scrutiny and challenge.

Good

Preventing crime and anti-social behaviour

Durham Constabulary is good at prevention and deterrence. In this section, we set out our main findings.

Main findings

The force prioritises preventing crime, anti-social behaviour and vulnerability

Preventing crime, anti-social behaviour and vulnerability are clear priorities for the force. These priorities are set out clearly in the force’s plan and everyone we spoke to understood them well. The force understands the strengths and needs of its local communities, and can identify those who are most at risk. Neighbourhood policing teams work with local area action partnerships, and police support volunteers to identify and resolve local concerns. The force has an effective performance management framework and leaders promote problem solving.

The force uses problem solving and works in partnership to prevent crime, anti‑social behaviour and vulnerability

All police officers and staff have had training in problem-solving techniques, using the OSARA model. The force holds regular problem-solving masterclasses to maintain knowledge and competence.

The force has a tiered approach to problem solving. Problem profiles describe the nature and scale of local concerns. The profiles are managed by neighbourhood policing teams. But it is often unclear how the force has responded to the problem. We found that profiles often lacked information on the response to the matter and any assessment of the result.

Problem-oriented policing (POP) plans are used to record how the full OSARA model has been applied. The most serious or complex problems have a full POP plan, including detailed analysis and assessment. To reduce bureaucracy, less complex problems are addressed using an abridged version, ‘POP on a page’.

The force has a strategic problem-solving group, which shares good practice. A network of over 20 POP mentors throughout the force champion and support problem-solving activity.

The force works well with a range of other organisations, including local community peer mentors. These mentors support (often vulnerable) people who place a disproportionately high demand on local services.

We saw many good examples of problem solving, particularly at the strategic level. Indeed, many of the force’s established projects have their origins in POP plans. These include:

- Edge of Care, an initiative to identify and address the risk factors associated with looked after children;

- the multi-agency tasking and coordination process, working with perpetrators and victims of domestic abuse; and

- Checkpoint, a deferred prosecution scheme designed to reduce re-offending by addressing the underlying causes.

We also found good evidence that the force evaluates the effectiveness of POP plans, often with support from local universities.

The force understands the demand facing neighbourhood policing teams and manages resources in line with that demand

The force understands the demand it faces and uses this to inform its resourcing decisions. The operating model is built around a neighbourhood approach. The force spends around 10 percent of its budget on neighbourhood policing. This is slightly above the average of forces in England and Wales (of 8.1 percent).

At the start of the pandemic, the force moved resources from neighbourhood teams. This was to make sure that it could continue to provide a 24-hour emergency response. These resources were quickly returned when demand allowed. Apart from this exception, removing officers from neighbourhood teams is tightly managed.

Senior leaders recognise and value the importance of neighbourhood policing. And they make sure that they have time for continuing professional development opportunities. The force also holds annual awards to recognise good problem-solving work.

Good

Responding to the public

Durham Constabulary is good at responding to the public. In this section, we set out our main findings.

Main findings

The force identifies and understands risk effectively at initial contact

The force normally answers calls from the public promptly. It regularly achieves, or exceeds, the target for answering 999 and 101 calls. It consistently applies a structured approach to assessing risk. All contact management staff are trained in applying THRIVE. When appropriate, callers are given advice on preserving evidence or crime prevention. Call handlers are good at looking for, and identifying, vulnerability.

Mental health practitioners in the control room provide professional advice and guidance. This allows the force to respond to people who have mental health problems or are in crisis, and to provide prompt support and intervention.

Members of the public can also contact the force using an online chat service, the use of which increased during the pandemic.

The force responds appropriately to incidents, including those involving vulnerable people

The force generally responds to incidents promptly. But, as stated earlier, we did find some evidence of appointment or response times being changed. This was more likely to happen at busy times. Attending officers are told of any identified risks or problems, including vulnerability, before they arrive. The force has introduced a real-time intelligence team in the control room. This team researches incidents involving vulnerability, including domestic incidents, to provide the attending officers with as much information as possible.

Officers look for signs of vulnerability when attending incidents – for example, children exposed to domestic abuse or any signs of exploitation. Any vulnerability identified is reported using the force’s safeguarding forms. All officers were clear on their responsibilities to safeguard vulnerable people. When responding to reports of crime, officers generally take time to apply initial ‘golden hour’ crime scene principles to secure and preserve evidence.

The force understands the demand faced by officers responding to calls for service and manages resources appropriately

The force understands the demand its response officers face. This is reflected in how it allocates resources. The current shift pattern for response officers aligns resources with demand, without necessarily taking staff wellbeing into account. The force is aware of this and plans to introduce a new shift pattern in 2022. This new shift pattern will better match resources to anticipated demand, while also improving staff wellbeing. There will also be more response officers. These will come from the extra resources provided as part of the national police officer uplift programme. Daily locality meetings are held in each of the four policing areas. The meetings review anticipated demand levels and allow senior managers to allocate resources flexibly.

The force understands the wellbeing needs of its contact management staff and officers responding to emergency calls

The force is aware of the pressures in the control room. There is a high turnover of staff. Many call handlers and dispatch staff use the position as a stepping stone to becoming a police officer or community support officer, and the force cannot compete with the salaries that commercial call centres offer. So it has decided not to carry any vacancies in the control room. Instead, it routinely resources at or above established staffing levels, which provides a degree of resilience. Control room staff are also given ‘protected time’ to complete continuing professional development activities.

The force takes the wellbeing of contact management and response staff seriously. Supervisors were widely seen as being supportive and focused on welfare. Most staff reported having monthly one-to-one meetings with their supervisor that were focused on welfare. Almost everyone we spoke to about wellbeing mentioned the force’s approach to trauma risk management. Anyone can identify an incident as potentially traumatic, and flag this on the command and control system. Once flagged, a member of the welfare team contacts every member of staff involved in the incident, from the initial call taker to response officers and supervisors, within 24 hours. They are offered help and advice on coping with the trauma and referred to support services if necessary.

Good

Investigating crime

Durham Constabulary is good at investigating crime.

Main findings

In this section, we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force investigates crime.

The force understands how to carry out quality investigations on behalf of victims and their families

The force recognises that an investigation starts with an initial report and it has provided staff in the control room with basic investigative training. This enables them to consider investigative opportunities at the earliest stage. The force has governance mechanisms in place to monitor and oversee standards of investigation, including results and victim satisfaction levels.

The force understands the crime demand it faces and what resources it needs to meet it effectively

The force has a comprehensive understanding of the crime demand that it faces. It uses this to inform resourcing decisions. While there remain vacancies in investigator posts, the force has a plan to fill these. It has recently increased the number of police and civilian investigators in safeguarding. The demand for digital forensic work continues to increase. But a triage and prioritisation process makes sure that this doesn’t delay investigations.

The force provides a quality service to victims of crime

The force responded positively and promptly to feedback following our review of investigation case files for the victim service assessment. In particular, we found that members of the workforce were much better at using investigative plans. These now appear as a series of actions for investigators to complete. We also found evidence of more effective supervisory oversight and review, although this would benefit from more clarity on how often supervisors should review investigations.

All crimes are assessed for investigative opportunities and receive a proportionate investigation. Crimes are allocated to an appropriate investigator based on the level of threat, harm and complexity. We found that this generally worked well, with managers intervening when necessary.

The force monitors levels of unsupportive prosecutions. These are cases where a suspect has been identified but the victim doesn’t want to support a police prosecution. Many officers gave examples of where they had pursued such cases, particularly those involving domestic abuse.

The force has provided officers with training on recent legislative and procedural changes. Recent changes include:

- the Director of Public Prosecution’s guidance on charging;

- the Attorney General’s guidelines on disclosure; and

- the Code of Practice for Victims.

The training has been via online learning, partly due to the pandemic restrictions. The force is monitoring the impact of these changes and, while the time taken to prepare some case files has increased, improvements in file quality mean that officers are getting more cases right first time.

Investigating officers maintain regular contact with victims and witnesses. But the recording of this could be more obvious and consistent. All officers were clear about their safeguarding responsibilities. And victims and witnesses who are vulnerable are referred to other organisations for support.

The force monitors the results of investigations to ensure integrity and identify any areas where it can improve. As a result, a flowchart now guides officers in making the right decisions. Staff from the crime management unit carry out monthly quality assurance checks of outcomes. These have confirmed that more accurate and consistent results are recorded when officers use the flowchart. Another recent quality assurance review focused on domestic abuse cases that had been finalised using outcome 16 (suspect identified, evidential difficulties, victim not supportive). Of the 298 cases reviewed, 274 were found to be correctly finalised. Twenty of the 24 cases were amended to outcome 15 because, while the victim did not support a criminal justice result, they supported the suspect being warned.

The force manages the wellbeing of staff involved in investigations

The force takes the wellbeing of those involved in investigations seriously. Senior managers recognise the particular demands on those who deal with the most serious and often distressing offences, such as rape and child abuse. Staff in these roles are given annual screening appointments with the occupational health unit. Line managers hold monthly one-to-one meetings with their staff, with a focus on wellbeing. Almost everyone we spoke to felt that line managers were supportive and took wellbeing seriously. Several teams had taken part in force wellbeing days, with activities ranging from mindfulness sessions to team-building exercises. Staff were also able to book wellbeing weekends at the police treatment centre. In most cases, investigative workloads were found to be reasonable and manageable.

Good

Protecting vulnerable people

Durham Constabulary is good at protecting vulnerable people. In this section, we set out our main findings.

Main findings

The force understands the nature and scale of vulnerability

The force’s strategy identifies 15 strands of vulnerability. And the strategic management group oversees progress.

The force has further developed a series of problem profiles. These cover a range of vulnerability-related matters such as domestic abuse, child sexual exploitation and abuse, and human trafficking and modern slavery. Operational delivery groups oversee progress against the supporting action plans and report to the strategic management group.

The force is involved in a wide range of collaborative arrangements with other organisations. These include multi-agency safeguarding hubs (MASHs) and a domestic abuse and sexual violence executive group. Following the kidnap and murder of Sarah Everard in London, the force has launched a listening exercise to understand local perceptions of violence against women and girls.

The force provides continuing safeguarding support for vulnerable people

Everyone we talked to was clear about their responsibility to provide safeguarding support to vulnerable people. Officers who attend incidents involving vulnerable people are aware that they are responsible for safeguarding until they hand over to someone else. Safeguarding forms are completed for vulnerable children and adults. These are recorded on the force’s Red Sigma computer system. Domestic abuse, stalking and harassment forms are completed following a domestic incident. Red Sigma automatically routes all safeguarding forms to the MASH, where specialist staff review and assess them. This makes sure that appropriate referrals are, or have been, made to other organisations for support. We heard good evidence that, when attending incidents, officers use their professional curiosity to look for signs of exploitation, hidden harm and vulnerability.

At the start of the pandemic, the force raised awareness among the public of the increased risk of domestic abuse during lockdown and the support available to victims of abuse. In part, this involved the force’s domestic abuse innovation officers contacting high-risk repeat victims if they hadn’t recently reported an incident. This was to make sure that they were safe and well. The force makes good use of the domestic violence disclosure scheme (Clare’s Law). Applications under the right to ask and right to know are considered, and prioritised, by the MASH. Detective inspectors make decisions on disclosure, with safeguarding officers providing the disclosure. This ensures a consistent approach. We found that applications were being dealt with promptly and there was no backlog. Officers are encouraged to take positive action when dealing with domestic abuse incidents. This can include arresting the perpetrator or applying for domestic violence protection notices and orders when appropriate.

The force works with other organisations to keep vulnerable people safe

The force works well with other groups to keep vulnerable people safe. MASHs bring together police and other organisations at sites in Durham and Darlington. COVID restrictions meant that it was difficult to attend the MASH in person. And we were told that it took four to five weeks to set up alternative arrangements with appropriate supporting technology.

Together with other organisations, the force provides a co-ordinated and tiered approach to managing the victims and perpetrators of the most serious crimes, including domestic abuse. Multi-agency public protection arrangements and multi‑agency risk assessment conferences manage those victims most at risk. Medium-risk cases are referred to the multi-agency tasking and co-ordination group. Perpetrators assessed as standard risk are considered for Checkpoint. This is a scheme that defers prosecution while the offender takes part in activity to address their offending behaviour. During our inspection, many of these meetings were held using video-conferencing technology. We were told that this meant that more people from other organisations attended and took part. We observed several of these virtual meetings and were impressed to see information being shared, driven by a commitment to keep people safe.

The force uses an independent organisation to survey victims of domestic abuse each month. It uses the results to identify opportunities to improve its service.

The force understands demand and resources, including working with other agencies

The force understands the demand it faces and the resources it needs. This is captured in a series of problem profiles, built using data from the force and other organisations. Examples include a comprehensive domestic abuse profile and another on child sexual abuse and exploitation. The force records a higher proportion of domestic abuse incidents and crimes than most forces in England and Wales. It also has a higher proportion of positive results in these cases. The force has examined this, together with the other organisations, and has had another force peer review its data and processes. As a result, it is confident that the data is accurate. The force recently increased the number of investigators in safeguarding, public protection, and child abuse and sexual exploitation. During our inspection, workloads were generally manageable. This confirmed that resources were matched to demand.

The force maintains and improves the wellbeing of staff involved in protecting vulnerable people

The force supports the wellbeing of staff working to protect vulnerable people. This includes mandatory, annual, occupational health reviews for everyone working in the most distressing areas of vulnerability, such as child sexual abuse and exploitation or investigating indecent images. Staff we spoke to felt that line managers were supportive and approachable. The force requires line managers to have monthly performance reviews with their staff, which should include checking on the individual’s welfare. Most of the people we spoke with said that their line manager was supportive and approachable, and confirmed that the monthly meetings were taking place. Wellbeing is a standing item on the agenda for all leadership meetings. This is an opportunity for senior managers to identify and address any emerging problems. The force is currently examining the concept of compassion fatigue. This involves assessing whether those who regularly deal with particularly distressing situations might build up an increased tolerance to what they see. And, if so, what safeguards the force could put in place to prevent this.

Good

Managing offenders and suspects

Durham Constabulary is good at managing offenders and suspects.

Main findings

In this section, we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force manages offenders and suspects.

The force is effective in apprehending and managing suspects and offenders to protect the public from harm

The force has improved how it manages and apprehends suspects and offenders. Outstanding suspects are discussed at the daily locality meeting. These meetings are held each morning in the force’s four police areas. Suspects who pose the greatest risk, or are the most difficult to apprehend, are escalated for targeting by force resources. Managers can easily access the information they need via a series of online dashboards. These dashboards are used to monitor the use of police bail, released under investigation and voluntary attendance. The use of voluntary attendance increased during the pandemic. This reduced the number of people being brought into custody, while allowing offenders to be brought to justice. There is an automated process that makes sure that the ACPO Criminal Records Office (ACRO) is notified of all foreign nationals arrested in the force area. ACRO is the unit that manages criminal records information.

The force is effective in managing the risk that registered sex offenders pose

During our inspection, there were 917 registered sex offenders living in the force area. Specialist officers in the MOSOVO unit are responsible for assessing and managing the risk these offenders pose. They use the active risk management system (ARMS) to assess levels of risk. All registered sex offenders are flagged on the force computer system and neighbourhood police staff are aware of those who live in their area.

Around 40 officers from neighbourhood policing teams volunteered to help manage low- and some medium-risk offenders. These officers are trained in risk assessing and managing offenders. Although a recognised, external expert provides the training, the force doesn’t currently have a trainer accredited by the College of Policing. But it does have three officers booked on the College’s ‘Train the trainer’ course.

We found the quality of ARMS assessment to be generally good. Assessments are completed promptly and there was no backlog. The force has an automated process that makes sure that all registered sex offenders are checked against the police national database every eight weeks. The offender manager is then notified of any change in intelligence or offending.

The College of Policing guidance on managing registered sex offenders is in the form of authorised professional practice (APP). The force doesn’t comply with all aspects of APP. For example, the guidance states that offenders who are the subject of a live court order shouldn’t be placed on reactive management. Yet the force has placed several such offenders on reactive management, based on a risk assessment of the intelligence and lack of offending. The chief constable has written to the National Police Chiefs’ Council’s lead suggesting that this is unnecessary and unsustainable, and asking for the matter to be reconsidered. The guidance also states that officers visiting offenders’ homes should be in plain clothes. While this is the case with visits by the MOSOVO team, chief officers have decided that neighbourhood teams should visit in uniform unless there is a reason not to. This is on the basis that neighbourhood officers are well known in their areas and it would arouse more suspicion within communities if they were to visit in plain clothes.

There is a positive and supportive relationship between the specialists and neighbourhood officers. But we found that some neighbourhood officers weren’t clear about what was expected of them when visiting registered sex offenders. The guidance advises that officers don’t carry out the visits alone. Some officers said that they routinely did visits alone, while others said that they would always be joined by another officer. Some were unclear as to whether they could examine computers and mobile devices during these visits, or whether this needed directed surveillance authorisation. The force should provide clarity on these matters.

The force uses ancillary orders well. In particular, it has seen an increase in applications for sexual harm prevention orders in the past 12 months. Breaches of orders are treated seriously and responded to promptly. The force has systems in place to proactively identify when indecent images of children are shared. It has a small team of specialist officers who are responsible for assessing risk and making sure that prompt action is taken to safeguard identifiable children and bring offenders to justice.

The force has an effective integrated offender management programme

The force takes a multi-track approach to integrated offender management. Domestic abuse perpetrators who don’t meet the threshold for a multi-agency risk assessment conference are referred to the multi-agency tasking and co-ordination group (MATAC). The organisations that make up MATAC support victims and offenders in breaking the cycle of offending.

Prolific and persistent offenders who commit disproportionately high levels of serious acquisitive crime, such as robbery or burglary, are considered for the integrated offender management programme. Led by the probation service, offender managers work with them to reduce re-offending. Offenders who are not considered for any of these schemes are assessed for Checkpoint.

Checkpoint offers offenders the chance to avoid prosecution if they work to change their behaviour. Independent Checkpoint navigators carry out a detailed needs assessment to identify the reasons for offending. Navigators then guide offenders to appropriate support services. Some of the navigators have been through the Checkpoint programme as offenders. They now use their experience and knowledge to guide others though the change process.

This multi-faceted approach to offender management means that the force is in a good position to implement the Government’s recently revised neighbourhood crime and integrated offender management strategy: Fixed, Flex, Free.

The force understands the demand and the resources it needs to manage suspects and offenders effectively

The force understands the demand it faces in managing suspects and offenders. And it has the capacity and capability to meet that demand. Resources are generally aligned to the identified threat and risk. And monitoring and governance are in the form of threat and risk meetings at local and force level. The force is clearly committed to reducing re-offending. It understands the strengths and limitations of the local organisations it works with. It actively evaluates the intended and actual results and benefits of initiatives. Independent institutions, including universities, often carry out these evaluations.

Good

Disrupting serious organised crime

Durham Constabulary is outstanding at managing serious and organised crime.

Main findings

In this section, we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force manages serious and organised crime.

The force is good at using all available intelligence to identify, understand and prioritise serious and organised crime. This helps inform effective decision making

The force understands the demand from serious and organised crime. It carries out an annual strategic assessment, which forms part of its force management statement (FMS). This directly informs force planning and resourcing decisions. There is a section in the FMS dedicated to serious and organised crime. This considers matters such as the number of active OCGs and potential disruption tactics.

The force has extremely effective systems in place to:

- carry out briefings;

- gather intelligence;

- work with other organisations; and

- assess the impact of serious and organised crime.

This means that the force understands the demand it faces and there is good oversight, which helps it manage its response to serious and organised crime. The effectiveness of the force’s efforts to tackle OCG activity is monitored through monthly locality and force-level threat and risk meetings. The force works well with the regional organised crime unit.

The force has been quick to understand, and put in place, the new ‘whole system’ approach to serious and organised crime, and the subsequent objectives around the national strategy. And it has a good grasp of what this will involve, in terms of demand, resources and capacity. The force will apply its existing bronze, silver, gold system to deal with the relevant changes. It is in a good position, in terms of partnership working, to continue its disruption activity. Its focus on high harm and vulnerability should mean that it is well placed to make good progress in this area.

The force has the right systems, processes, people and skills to tackle serious and organised crime and keep the public safe

The force has the capacity and capability to meet the demand it faces in terms of serious and organised crime. The leadership and culture are evident throughout the organisation. The serious and organised crime unit is made up of officers with a varied skill set. The unit is well supported by the digital intelligence unit, the dedicated surveillance team and other specialist units. This allows the force to identify the demand and react accordingly.

The force does have concerns around a gap in training for surveillance skills. This is a national problem, made worse by a decline in training provision during the pandemic. This isn’t just a problem for Durham Constabulary.

Working closely with the regional organised crime unit and neighbouring forces, Durham Constabulary can access additional specialist capacity and capability when needed. The force makes clear the responsibilities of those carrying out key roles in tackling serious and organised crime.

The OCG disruption team provides support and guidance to local responsible officers. This helps them develop tactical plans for OCGs and priority individuals under lifetime offender management. Officers also have access to an online toolkit, which provides a range of information and advice. The OCG disruption team supports the partnership disruption panel, and locality threat and risk meetings. It also educates other organisations on tactics that OCGs commonly use to corrupt staff and officials. The force has robust procedures in place to identify and tackle potential corruption. And it carries out regular financial health checks on staff.

Disruption activity reduces the threat from serious and organised crime

The force prioritises offences that cause serious harm. This, combined with a focus on vulnerability, means that it makes robust decisions around threat, harm and risk. Consequently, the results of operations are often positive. Specialist teams support local responsible officers. This involves a financial investigator and digital media investigator being allocated to every OCG investigation. For example, the economic crime team identified funds that an OCG member hadn’t declared. This provided an opportunity to tackle this via HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC). There is a shared commitment to disrupting OCGs to reduce the harm they cause. During the pandemic, the force used emergency legislation to tackle and disrupt OCGs.

The force works well with other organisations that tackle serious and organised crime, and has access to their specialist resources when needed. The chief officer lead also chairs the regional serious and organised crime tasking group. And we saw clear evidence that there was a joint regional focus on tackling the highest priority matters. Several operations were discussed where forces were working together effectively. Investigative plans are developed with force specialist leads, as well as the experience other organisations bring.

Disruption panel meetings provide a forum to review existing plans and plan future activity. This close partnership working promotes an excellent response to tactical disruption. For example, a recent operation in the Peterlee area, targeting fast‑food outlets, saw excellent co-operation between 12 other agencies. These included the Health and Safety Executive, local authority housing department and HMRC. As well as a positive result, it further improved intelligence sharing.

Our observation of the disruption panel meetings confirmed the vibrant relationship that exists with other organisations, and which is effective in tackling serious and organised crime. The OCG disruption team, and its lead, make a significant contribution to every aspect of how the force tackles serious and organised crime. The team lead co-ordinates activity, with a focus across the 4Ps (Prevent, Pursue, Protect, and Prepare). The passion to reduce the impact of this type of criminality is exceptional. The model of working supports local responsible officers and there is effective management, accountability and planning. Other forces would benefit from considering this approach, or aspects of it.

The force prevents people from engaging or re-engaging in organised crime

The force has a very clear focus on preventing vulnerable members of the community falling into organised criminal activity. It has well-established, inter-agency partnership working, which identifies such people. And it has used a wide range of tactics to address this threat.

The serious and organised crime local profile prioritises vulnerability. This informs the partnership response. Organisations the force works with agreed that this was also a focus for their own work. For example, social services and welfare workers who visit clients know how to respond to those who may be vulnerable to serious or organised crime. This has been driven by the ‘behind closed doors’ initiative the force promoted. The force’s approach to ‘Prevent’ activity in this area brings in other organisations as early as possible. It raises awareness of this approach among the organisations it works with. The OCG disruption panel is a good example of this, encouraging members to bring recommendations and actions to the table for open discussion and sharing intelligence.

The cyber prevent and protect team works with younger people who are involved in hacking or cyber attacks. The aim is to divert them away from these activities. The force’s vulnerability tracker identifies vulnerable people at risk of being drawn into serious and organised crime, which allows the force to take appropriate preventative action. The economic crime team is aware of vulnerable victims who may be exploited through money laundering. In these cases, seize and desist notices are used and the MASH considers safeguarding action.

The creation of MARSOC (Multi-Agency Approach to Serious and Organised Crime) has led to some uncertainty about the force’s role in lifetime offender management. This was also evident at a regional level. The force currently oversees lifetime offender management well through its OCG meetings. And it is good at using serious crime prevention orders, which are managed by the OCG disruption team.

The force helps communities, organisations and individuals to be resistant and resilient to the impact of serious and organised crime

The force works with organisations and local communities to reduce tolerance to organised crime. Most local responsible officers are neighbourhood inspectors or sergeants. Area action partnerships are chaired by local neighbourhood supervisors. They bring together the police and local partners, with a focus on protecting local communities from harm. Local responsible officers provide updates and information on serious and organised crime at every partnership meeting. This gives all those at the meetings a better understanding of exploitation and greater awareness of vulnerable members of the community. These partnerships place emphasis on systemic approaches – for example, using early years intervention to support and guide, rather than the police arresting and criminalising vulnerable young people being exploited by OCGs.

Local neighbourhood policing teams understand and recognise the threat from serious and organised crime. They know who are vulnerable to exploitation or being drawn in. The force has helped local authority partners to improve their approach to serious and organised crime. Cyber prevent and protect officers also provide local businesses with support and advice about cyber attacks.

Read An inspection of the north-east regional response to serious and organised crime – December 2022

Outstanding

Meeting the strategic policing requirement

We don’t grade forces on this part of our assesment. In this section, we set out our main findings for how well Durham Constabulary meets the strategic policing requirement (SPR).

Main findings

In this section, we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force meets the SPR.

The force understands its expected contribution to the SPR

The force carries out a strategic threat and risk assessment to inform its strategic plans. It uses a structured approach and MoRiLE (the management of risk in law enforcement) to score and prioritise those threats. All six SPR threats are clearly set out in the police and crime plan, the force management statement and the ‘plan‑on-a-page’. The force works well with statutory and voluntary organisations and plays an important part in the County Durham and Darlington local resilience forum. This was evident during the response to the pandemic.

The force assures itself that it continues to have the capacity and capability to respond to the SPR threats

The force has created a dedicated unit (SCORD) to oversee its preparation for, and response to, the six SPR threats. SCORD is headed by a superintendent. This department leads on three of the threats; cyber attacks, civil emergencies and public order. It also supports the remaining areas: terrorism, serious and organised crime, and child sexual abuse and exploitation (these remain the responsibility of specialist units).

SCORD is responsible for making sure that the force has the capability and capacity it needs to be able to respond to these threats, both now and in the future. This includes having enough staff trained, qualified and competent to carry out both operational and leadership roles. This is important because it allows the force to identify and make plans to fill future gaps in knowledge or skills. Durham Constabulary works well with neighbouring forces to make the most of regional capability and capacity.

The force plans effectively to meet changing and future demands posed by the six SPR threats

The force has a series of operational response and contingency plans in place to meet a wide range of anticipated threats. SCORD makes sure that these plans are regularly tested, and that the force has the capability and capacity available and equipped to respond. This is important because it means that the force can assure itself that contingency and response plans are appropriate. The department is also responsible for making sure that all exercises and test events are subject to a structured debrief. This helps to identify any changes that need to be made to plans, training or operating procedures. The testing and exercise regime was suspended while the force responded to the pandemic. But there are now plans to restart a full schedule of operational testing and exercising. This will begin with an internal cyber-related exercise. The programme will then expand to bring in organisations and the local resilience forum.

Protecting the public against armed threats

We don’t grade forces on this part of our assessment. In this section, we set out our main findings for how well Durham Constabulary protects communities from armed threats.

Main findings

The force has a reasonable understanding of its current and future operational requirements to meet the demand that needs an armed response

The force’s understanding of threats is set out in its armed policing strategic threat and risk assessment (APSTRA). The current APSTRA was developed with Cleveland Police, as part of the Cleveland and Durham strategic operations unit formal collaboration. The APSTRA is published annually and was being revised at the time of our inspection. The initial draft did not meet the national standards in several areas. For example, it did not include data on the use of Taser, armed deployment or the demand related to firearms. Although the revised APSTRA has not yet been published, the latest version satisfactorily addresses these concerns.

We found the force’s ability to respond to armed incidents to be effective. Armed response vehicles are available to meet the demand. And firearms commanders in Durham and Cleveland forces can deploy armed officers in either force area. There are good working relationships with all neighbouring forces and extra support is available if needed. Tactical advisers and intelligence experts are available 24/7 to support firearms commanders.

The force’s response to threats that need an armed response, or the use of weapons that are less lethal, is well led

The assistant chief constable is responsible for armed policing in Durham. This provides the force with strategic leadership. Governance is through the joint operations group, which brings together chief officers from Durham and Cleveland forces. We found that tactical and strategic firearms commanders are well trained, their performance is monitored and they are fit to carry out their responsibilities.

Officers in armed response vehicles resolve most armed incidents. But, together with Cleveland Police, Durham Constabulary maintains a specialist firearms capability. This is for incidents that need the expertise of more highly trained officers. The demand for, and use of, specialist capabilities in County Durham and Darlington is limited. Yet the cost of training such specialist officers is significant. The force should consider whether keeping this specialist capability represents value for money. How good specialist firearms commanders are at their job depends on their using the tactics and specialist munitions they are trained in. Not regularly taking part in these operations might mean that their skills deteriorate. The force should investigate other solutions for deploying specialist capabilities in the north-east region.

The force complies with national procedures for choosing, acquiring and using firearms, ammunition and specialist munitions

We reviewed the force’s procedures should they consider acquiring new weapon systems or specialist munitions. We found a good understanding of how to document these considerations. The chief officer needs to approve any decision to buy new weapons. And the joint operations group provides the necessary governance for such decisions on behalf of both forces. The force also recognises its responsibilities to the National Police Chiefs’ Council’s armed policing lead and the Home Office for these matters.

The force works well with neighbouring forces to share resources, build capacity and reduce the cost of armed policing

The strategic collaboration with Cleveland Police is currently under review. But we found that the Cleveland and Durham strategic operations unit responds effectively and seamlessly to firearms incidents in both force areas. The joint arrangements are firmly embedded, and the standards of training and deployment are the same in each force. This means that armed officers and firearms commanders can operate seamlessly in either force. Armed capacity is kept under regular review, and robust succession planning for recruiting armed officers and firearms commanders is clear.

Operational plans help the force respond to threats that need an armed response

We expect forces to have plans to address foreseeable threats. To test these, Durham Constabulary has been co-ordinating a programme of table-top and practical exercises with other organisations. The pandemic interrupted this programme, although it has now resumed.

The force has consistent, rigorous and reliable systems to review operational performance and make improvements

We found good engagement between operational, tactical and strategic firearms commanders in post-event debriefing procedures. De-brief reports are routinely submitted. Good ways of working and areas for improvement are identified and training programmes are adapted when necessary. But we found that individual officers who raise concerns could be given a more personalised and quicker response. We raised a similar matter in our last inspection and we expect the force to put this right.

The National Counter Terrorism Police Headquarters provides guidance on the role of unarmed officers in armed incidents. It provides instruction on officers’ main responsibilities, recognising that they are likely to be the first to respond to these incidents. Training has been made available to student officers in a digital format. This is yet to be rolled out to all frontline officers and concerns were raised to us about the safety of unarmed first responders. The constabulary should review the risk of this delay and its potential consequences.

Building, supporting and protecting the workforce

Durham Constabulary is good at building and developing its workforce.

Main findings

In this section, we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force builds and develops its workforce.

The force promotes an ethical and inclusive culture at all levels

The culture within Durham Constabulary is based on the chief constable’s values of positive; fair; courageous; inclusive; and with integrity. These are set out clearly in the force’s strategies, policies and plans. More importantly, everyone we talked to understood and applied them. There is a sense of pride in being part of Durham Constabulary and everyone talks of ‘doing the right thing’. This was confirmed when we spoke to staff association and trade union representatives, as well as others from a wide range of staff support networks.

Members of the workforce have a good understanding of the Code of Ethics, and feel valued and empowered to be themselves and challenge inappropriate behaviour. The force has a diversity, equality and inclusion strategy, and an inclusion charter. An action plan to support the strategy is monitored through the people board, chaired by the deputy chief constable.

The force understands the wellbeing of its workforce and uses this to develop effective plans to make further improvements

The force has a good understanding of the wellbeing of its workforce and has completed the Blue Light self-assessment. An action plan supports the wellbeing strategy. The plan has four parts, aimed at making sure that everyone is well; feels well; can access support; and supports each other. The plan covers both physical and psychological wellbeing. And the people board monitors progress.

The force regularly surveys its workforce to gauge opinion. As well as the annual staff survey, the force issued two more surveys during the pandemic (when many people were working from home). The results of these identified several concerns, which the force moved quickly to address. For example, the force quickly developed a system to allow staff working from home to order furniture and equipment to be delivered direct to their home.

The annual staff survey is carried out with support from Durham University. A comprehensive report is available on the force intranet. It sets out the full findings of the survey and the force’s response. A three-page summary is also circulated to all staff, highlighting the actions taken as a result of the survey. Staff we spoke to felt that managers and leaders were committed to improving wellbeing.

The force maintains and improves the wellbeing of its workforce and understands the effect of the action it is taking

The force has a wellbeing section on its intranet, which includes information, guidance and advice on all aspects of welfare and wellbeing. Following feedback that some staff were reluctant to access the system on workplace computers, the force launched its own wellbeing hub. This is hosted on the Police Knowledge website and can be accessed from personal computers and mobile devices. The force has publicised and promoted the hub to staff. We found that most were aware of it but very few had accessed it.

The force has recently increased staffing in the occupational health unit, which is provided by a third party. This has reduced referral and waiting times. Routine cases are now normally seen within seven days and priority cases can be fast-tracked. Staff were positive about these changes.

The force provides a range of preventive and proactive initiatives to improve the wellbeing of its workforce. In response to feedback from staff, it has recently installed gym equipment in each of the four local policing areas. This is to help staff maintain and improve their physical fitness. And a series of workshops on building personal resilience were well attended. Other workshops teach mindfulness. Teams and individuals can take advantage of wellbeing weekends, which are held at the police treatment centre. Staff with a disability can complete a disability passport. This reduces the stress of moving posts. The passport records relevant information, specifically any reasonable adjustments necessary to allow the individual to do their job. If they move post, the arrangement moves with them.

Many of the force’s shift patterns have been in place for a long time. And they don’t necessarily provide for a healthy work-life balance. The force has carried out a review and is considering new shift patterns for 2022. The review was informed by the results of a study by Durham University, which looked at the impact of sleep deprivation. While helping to improve wellbeing, the new shift pattern will also better match resources to demand.

The force has taken a proactive approach to managing stress and trauma. It has invested in trauma risk management (TRiM) processes to deal with trauma following an incident. It has also trained a small number of staff and officers in trauma impact processing techniques (TIPT). This enables them to spot the early signs of stress and trauma among colleagues, and to provide coping techniques and access to support services. Under the TRiM process, anyone involved in an incident that is likely to be traumatic can flag this on the command and control system. Within 24 hours, a member of the welfare team makes contact, by text message, with everyone involved. They make people aware of the support services that are available. Those who request it are contacted by a member of the welfare team and given the support they need. Even if it is initially declined, welfare will make contact again after seven days and remind people that support is available and how to access it.

The force is building its workforce for the future

The force understands its recruitment needs for both police officers and police staff. The force’s equality, diversity and inclusion strategy has two main aims. These are to ‘continue to live our values and promote inclusivity, equality, and diversity’ and to ‘inspire trust and confidence within the communities we serve’. An action plan supports the strategy. The people board monitors progress against the action plan.

The force understands its workforce in terms of representation and protected characteristics. According to the 2011 census, 2.2 percent of the population of County Durham and Darlington are from black, Asian or minority ethnic (BAME) backgrounds. This compared with 1.6 percent of the workforce at the time of our inspection. The force has a positive action co-ordinator. It is their job to improve the recruitment, retention and progression of people from under-represented groups, in particular those from BAME backgrounds. Because the BAME population in the force area is so low, as well as targeting local communities, the force attends recruitment fairs and targets university students from further afield. Regular positive action events encourage recruitment and explain the process. With the force taking on more police officers, it expects to see the proportion of staff from BAME backgrounds reach 2.2 percent during 2021.

The force has an established coaching and mentoring scheme with over 140 trained coaches. It works well with staff networks to better understand, and address, matters related to inclusion and protected characteristics. We heard of many examples of this. These include:

- an autism staff network providing one-to-one support to an applicant, which continues to their appointment;

- a series of mock promotion boards to encourage more women to apply for promotion; and

- extending maternity contracts to cover those undergoing fertility treatment or adoption.

The force is developing its workforce to be fit for the future

The force maintains a budgeted training plan that is updated annually. This identifies the known and predicted training requirements for the year ahead. As part of the national increase in police officer numbers, Durham will recruit 227 more officers over the next two years. Following a period of austerity, during which police officer numbers went down, this increase will put significantly more training demands on the force. It has responded by investing in the infrastructure, creating more classroom space at the training school and increasing the number of qualified trainers.

The force has adopted the new national policing educational qualifications framework. Its aim is to increase the educational standards of police officer recruits. Durham is one of a small number of forces to recruit officers under both the degree holder entry programme (DHEP) and the police constable degree apprenticeship (PCDA) scheme, with courses alternating between the DHEP and the PCDA. The force will phase out the previous initial police learning and development programme (IPLDP) in late 2022. The force has worked with Northumbria University to offer the new framework.

As well as the tutor constables, who provide operational guidance to student officers, the force has also recruited a team of assessors. This splits the role of teaching and assessment, and introduces an extra element of independence and greater objectivity to assess operational competence. The force reports that the standard of qualitative assessment has improved across the force, including in the IPLDP.

The force has a three-tiered, talent management system:

- Tier 1 is available to all staff.

- Tier 2 is open to anyone with a protected characteristic.

- Tier 3 is aimed at those identified as having the potential to become future leaders.

The force recently launched a revised system of professional development review. Under this new system, everyone must have at least three mandatory objectives. Extra objectives are optional. The mandatory objectives require commitment to continuing professional development; counter-corruption; and equality, diversity and inclusion. Line managers are required to hold monthly performance review meetings with their staff. These meetings are focused on assessing progress towards the objectives and staff welfare. When we spoke to staff, we found that, while most were aware of the changes, very few had completed the formal process. Many expressed the view that professional development review was for those seeking a specialist posting or promotion. But we were pleased to hear that, overall, the monthly performance review meetings between staff and line managers were being held.

The force recognised that all new police officers either join with, or will get, a degree‑level qualification. It has introduced a scheme whereby existing police officers and staff can apply for funding to complete degree courses. This is financed by the money the force receives for taking part in the national apprenticeship scheme. As well as staff feeling valued, the force also benefits because many people choose to study subjects related to their role. They then share their research and dissertations with the force.

Proactive and disruptive action that the force takes, and effective vetting management, reduce the threat and risk of police corruption

The force is good at managing the vetting of its workforce and fully complies with the national authorised professional practice. Good systems are in place to make sure that the vetting of all staff is reviewed regularly. The force identified that the ratio of posts designated as requiring an enhanced level of vetting was lower than the England and Wales average. A comprehensive review resulted in the ratio of designated posts rising from 17 percent to 24 percent. This put more demand on the vetting unit, with over 200 people needing enhanced vetting. The force has also seen increased recruitment as part of the national uplift programme. Despite these extra demands, we were pleased to find that there were no backlogs in the vetting process.

We were also pleased to find that, following this being highlighted as an area for improvement in our last inspection, the force now routinely monitors its vetting decisions. It specifically looks for any potential disproportionality. This is reported to the people board on a quarterly basis.

In our last report, we also commented on the lack of a counter-corruption strategic assessment, and the lack of capacity and capability within the counter-corruption unit (CCU). The force has since completed a strategic threat assessment, which takes account of regional and national threat assessments. And more staff have been recruited into the CCU since our last inspection, including an analytical capability. The force now has the capacity to develop counter-corruption intelligence and carry out investigations. At busy times, staff from the CCU help colleagues in the professional standards department. This is a conscious decision by the executive team to maximise efficiency. However, it does mean that time spent on reactive investigations cannot be spent proactively tackling corruption.

The force has a robust counter-corruption prevention programme. A Prevent officer leads on educating and raising awareness among officers, staff and other organisations that the force works with. Much of this work has focused on organisations that support vulnerable people and on raising awareness of the abuse of position for sexual purposes.

Effective processes are in place to monitor the use of the force’s information technology systems. The force’s professional development review system now includes integrity-related questions. And monthly performance review meetings with line managers give staff the opportunity to declare any business interests, potential inappropriate associations or other changes in personal circumstances.

Good

Strategic planning, organisational management and value for money

Durham Constabulary is outstanding at operating efficiently.

Main findings

In this section, we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force operates efficiently.

The force has an effective strategic planning and performance framework, ensuring that it tackles what is important locally and nationally

The force has a robust and comprehensive approach to strategic planning and performance management. This is underpinned by a co-ordinated approach to data collection and robust governance arrangements throughout the organisation.

The force has a good relationship with the Office of the Police and Crime Commissioner, which ensures its full integration with the police and crime plan. Its overarching strategy is set out clearly and concisely in the plan-on-a-page. And knowledge of the plan-on-a-page extends throughout the organisation and is clearly evident in performance management and governance structures.

Monthly threat and risk meetings are held at both the local and force levels. There are also bi-monthly resourcing meetings to align resources with demand. The strategic cyber and operational resource department scans the organisation for demand each day and can respond to meet increased demand. Daily locality meetings and weekly operational meetings allow the force to flex with changing demand.

The force manages current demand well

The force identifies both internal and external demand. Comprehensive governance structures make sure that appropriate information is available promptly throughout the force. It makes good use of technology, with information widely available to managers via dashboards. Briefings are on a daily and weekly basis, and monthly formal meetings review overall progress and performance.

The force has integrated force management statement (FMS) preparation into its strategic planning process. It uses the four-stage FMS process to review its current operating model.

The force makes sure that it has the capability and capacity it needs to meet and manage current demands efficiently

The force makes good use of HMICFRS value-for-money profiles. Benchmarking the cost of its services, it identifies potential savings and improvements. This is supported by an efficiency plan, which identifies opportunities to improve efficiency and reduce waste. Examples include:

- providing performance information automatically through applications such as Microsoft Power BI–Business data analytics;

- allocating officers tasks via mobile devices so that they don’t need to attend briefings; and

- changes to police staff contracts to increase home working, reduce accommodation needs and improve wellbeing.

Recognising a skills gap throughout the organisation, the force introduced the digital leadership programme. This provides modular training to help staff and officers at all levels better manage in an increasingly digital environment. This training is now being provided to other forces.

We found little evidence of inefficient internal demand. The police officer overtime claim process remains largely manual. While providing a good level of control and detailed financial reporting, it may not be the best use of officers’ time. The force is aware of this but does not see it as a priority for change.

The force understands future demand and is planning to make sure that it has the right resources in place to meet future needs

The force uses the FMS approach to identify predicted demand over the next four years. By integrating this preparation into the strategic planning process, the force ensures that these predictions are considered when making future resourcing decisions. During the pandemic, the force identified the benefits and risks of the different ways of working. This prompted reviews of its existing strategies, including those for its estates and vehicle fleet, to ensure that they meet future needs.

The force makes the best use of its finances, and its plans are both ambitious and sustainable

The force has a balanced budget over the next three years, with an identified shortfall in year four. This is due to planned capital investment and, in particular, the emergency services mobile communication programme. But the current investment plan has funding and uses existing resources without the need to borrow.

The proposed single custody centre accounts for most of the force’s capital expenditure. When complete, it should provide the force with more opportunities to reduce the accommodation it needs, increase the level of capital receipts and reduce the running costs. The force has taken a cautious approach to these potential savings by not including them in existing medium-term financial plans.

Durham’s assistant chief officer developed the funding model for the national uplift in police officer numbers. By applying the model, the revenue budget includes the full costs of the uplift programme across its lifetime, not just the three years of growth.

The force plans to reduce the level of reserves substantially from just over £30m to around £10m. Reserves have built up through capital receipts and revenue to fund the capital programme. This includes the custody suite. The level of unmarked reserves remains steady throughout the forecast period, at just under £7m. This represents approximately 5 percent of revenue expenditure.

The force actively seeks opportunities to improve services through working with others and makes the most of these benefits in line with its statutory obligations

The force has taken a considered approach to engaging with other forces and organisations, both on an operational and support service level. The governance processes are robust. We saw evidence of review and, in some instances, withdrawal from collaboration when it was considered not to be in the best interests of the force to continue.

Some progress has been made with sharing accommodation with the County Durham and Darlington Fire and Rescue Service. This appears limited but may provide further benefits. It would be good to wait for clarity on proposed changes to governance structures before moving forward.