Overall summary

Our judgments

Our inspection assessed how good Cumbria Constabulary is in 11 areas of policing. We make graded judgments in 10 of these 11 as follows:

We also inspected how effective a service Cumbria Constabulary gives to victims of crime. We don’t make a graded judgment in this overall area.

We set out our detailed findings about things the force is doing well and where the force should improve in the rest of this report.

Important changes to PEEL

In 2014, we introduced our police effectiveness, efficiency and legitimacy (PEEL) inspections, which assess the performance of all 43 police forces in England and Wales. Since then, we have been continuously adapting our approach and this year has seen the most significant changes yet.

We are moving to a more intelligence-led, continual assessment approach, rather than the annual PEEL inspections we used in previous years. For instance, we have integrated our rolling crime data integrity inspections into these PEEL assessments. Our PEEL victim service assessment will now include a crime data integrity element in at least every other assessment. We have also changed our approach to graded judgments. We now assess forces against the characteristics of good performance, set out in the PEEL Assessment Framework 2021/22, and we more clearly link our judgments to causes of concern and areas for improvement. We have also expanded our previous four-tier system of judgments to five tiers. As a result, we can state more precisely where we consider improvement is needed and highlight more effectively the best ways of doing things.

However, these changes mean that it isn’t possible to make direct comparisons between the grades awarded this year with those from previous PEEL inspections. A reduction in grade, particularly from good to adequate, doesn’t necessarily mean that there has been a reduction in performance, unless we say so in the report.

HM Inspector’s observations

I congratulate Cumbria Constabulary on its performance in keeping people safe and reducing crime, although it needs to improve in some areas to provide a consistently good service.

These are the findings I consider most important from our assessments of the force over the past year.

The force’s work in the management of registered sex offenders is excellent, which means it is protecting communities from some of the highest-harm offenders

The force values this area of work and the investment is evident. I am impressed by some of the innovative practice observed during this inspection. The force is proactive in its management of registered sex offenders, and officers and staff feel valued and supported by senior leaders.

The force has a positive, supportive and inclusive culture

The force is investing in the workforce and I am impressed to hear about the positive culture. Everybody we spoke to during our inspection said that they felt proud to work for Cumbria Constabulary.

The force has a strong focus on early intervention with children and young people, underpinned by its child-centred policing model

I am encouraged to see the child-centred policing model that the force has adopted. Through a mix of early intervention and education, the force is working to support children and young people to make sure they don’t become involved in crime and anti-social behaviour.

The force is digitally progressive and innovative

The force has made significant investment in its digital transformation programme. I am encouraged to see that digital technology is being used to reduce inefficiencies and support those on the front line to carry out their roles effectively.

The force needs to improve its call handling performance and abandonment rates for non-emergency calls

The force’s overall call handling performance is good. Emergency calls are answered and responded to quickly; however, sometimes abandonment rates for non-emergency calls aren’t meeting national standards. I am reassured that the force has been taking steps to address this following our inspection.

The force needs to review its neighbourhood policing resourcing and deployment model

The force has effective working arrangements in place with some of its partner organisations, but it needs to make sure that its resourcing and deployment model is fit for purpose and based on an understanding of neighbourhood demand. I am reassured that the force has been developing plans for this work that will take into account the continuing local government review.

My report now sets out the fuller findings of this inspection. While I congratulate the officers and staff of Cumbria Constabulary for their efforts in keeping the public safe, I will monitor the progress towards addressing any areas I have identified where the force can improve further.

Andy Cooke

HM Chief Inspector of Constabulary

Providing a service to the victims of crime

Victim service assessment

This section describes our assessment of the service victims receive from Cumbria Constabulary, from the point of reporting a crime through to the outcome. As part of this assessment, we reviewed 130 case files as well as 20 cautions, community resolutions and cases where a suspect was identified but the victim didn’t support, or withdrew support for, police action. While this assessment is ungraded, it influences graded judgments in the other areas we have inspected.

The force answers emergency calls quickly, but it needs to answer non‑emergency calls more quickly

When a victim contacts the police, it is important that their call is answered quickly and that the right information is recorded accurately on police systems. The caller should be spoken to in a professional manner. The information should be assessed, taking into consideration threat, harm, risk and vulnerability. And the victim should get appropriate safeguarding advice.

Emergency calls were answered well, but the force needs to improve the time it takes to answer non-emergency calls. When calls are answered, the victim’s vulnerability is assessed using a structured process but repeat victims aren’t always identified. This means this isn’t considered when deciding on the police response. We found that not all victims were given crime-prevention advice or advice on the preservation of evidence. This can lead to the loss of evidence to support investigations, or lost opportunities to prevent further crimes being committed.

The force responds to most calls for service in a timely way

A force should aim to respond to calls for service within its published time frames, based on the prioritisation given to the call. It should change call priority only if the original prioritisation is deemed inappropriate, or if further information suggests a change is needed. The response should take into consideration risk and victim vulnerability, including information obtained after the call.

We found that on most occasions the force responds to calls appropriately. But sometimes the response took longer than recognised force timescales and the victim’s expectations weren’t met. This means that victims may lose confidence and withdraw from investigations. For non-emergency calls the force uses an appointment system to respond to some incidents. This is used effectively, and we found that staff were appropriately allocated to respond to incidents.

The force allocates crimes to appropriate staff, and victims are promptly informed if their crime isn’t going to be investigated further

Police forces should have a policy to make sure crimes are allocated to appropriately trained officers or staff for investigation or, if appropriate, not investigated further. The policy should be applied consistently. The victim of the crime should be kept informed of the allocation and whether the crime is to be further investigated.

The arrangements for allocating recorded crimes for investigation are in accordance with the force policy. In all cases we looked at, the crime was allocated to the most appropriate department for further investigation. We found that victims were always informed promptly when their crime report wouldn’t be investigated further. This is important as it means that victims are provided with an appropriate level of service.

Most investigations are effective, and victims are given the appropriate level of advice and support for the crime

Police forces should investigate reported crimes quickly, proportionately and thoroughly. Victims should be kept updated about the investigation and the force should have effective governance arrangements to make sure investigation standards are high.

Most investigations were carried out in a timely manner, and relevant and proportionate lines of enquiry were also completed in most cases we looked at. Investigations are appropriately supervised, and victims are kept updated throughout. This is positive as victims are more likely to have confidence in a police investigation when they are regularly updated at important stages. A thorough investigation increases the likelihood of perpetrators being identified and a positive outcome for the victim.

Victim personal statements aren’t always taken, which can deprive victims of the opportunity to describe the impact that crime has had on their lives. When victims withdraw support for an investigation, the force doesn’t always consider whether it has enough evidence to continue with the case regardless. Evidence-led prosecutions can be an important method of safeguarding the victim and preventing further offences. The force considers the use of orders designed to protect victims, such as a domestic violence protection notice or order, in most cases.

Under the Victims’ Code of Practice (VCOP) there is a requirement to conduct a needs assessment at an early stage to decide whether the victim needs any additional support. The result of the assessment and the request for additional support should be recorded. The force usually completes the victim needs assessment, which means victims are more likely to get the appropriate level of service.

The force doesn’t always finalise reports of crimes appropriately and sometimes fails to consult the victims and record their views

The force should make sure it follows national guidance and rules for deciding the outcome of each report of crime. In deciding the outcome, the force should consider the nature of the crime, the offender and the victim. And the force should show the necessary leadership and culture to make sure the use of outcomes is appropriate.

In appropriate cases, offenders who are brought to justice can be dealt with by means of a caution or community resolution. To be correctly applied and recorded, it must be appropriate for the offender and the views of the victim must be considered.

Our inspection found that community resolutions were used correctly, with offenders having met the national criteria for the use of this outcome. Victims are consulted and their views are recorded. But we found that several cautions had been incorrectly applied. This was due to the nature of the offence, or the offender not being suitable for a caution. Victims aren’t always consulted, and sometimes their views aren’t recorded. Where a suspect is identified but the victim doesn’t support, or withdraws support for, police action, the force should make sure it has an auditable record to confirm the victim’s decision so it can close the investigation. In some cases, this outcome had been incorrectly applied and evidence of the victim’s decision was also often absent. This means there is a risk that the victim’s wishes may not be fully considered before the crime is finalised.

Engaging with and treating the public with fairness and respect

Cumbria Constabulary is adequate at treating people fairly and with respect.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to treating people fairly and with respect.

The force is improving the way it understands the diverse needs of its communities, but there is more work to do

The resident population of the county of Cumbria isn’t culturally diverse when compared to some other areas of England and Wales. A large number of tourists visit the county each year, however, and this transient population is more diverse.

It is important that the force understands the diverse needs of its communities and works with them to build their trust and confidence, so it can resolve local issues that are affecting them. The force has carried out community mapping to help it understand the diverse make-up of its communities.

We found some examples of police community support officers (PCSOs) being proactive in identifying harder-to-reach communities and working to build relationships and trust. One example of this was in the west territorial policing area, where PCSOs have been working with the council’s refugee co-ordination team to help integrate Syrian refugees into the community. This is positive as it means that where relationships have been developed, communities will be more likely to contact the police when they are in need. We also found that in one area the neighbourhood inspector had been holding meetings with the charity Multicultural Cumbria, to seek advice on better ways to identify and work with diverse communities. While there is still work to do, we are reassured by the activity that the force is carrying out in this important area.

Where diverse communities have been identified, the force has plans in place for working with them. But we found the understanding of its communities greater in some areas of the force than others. The force recognises there are some gaps in understanding and that it can’t say with confidence that the diversity of its communities, especially those that are harder to reach, is fully known.

The force works with communities to understand their needs, but sometimes contact is made only when needed rather than through regularly working together in a structured, continuing way

The force’s Community Engagement and Consultation Strategy 2019–22 sets out minimum standards for how the force should work together with its communities to understand their needs. The strategy is supported by plans to work with communities based on methods of informing, consulting and participating.

The plans set out the activity the force intends to carry out, to gather intelligence and to seek community views to help it set policing priorities. There are a range of methods outlined in the plans that the force uses to communicate with the public. These include mobile or pop-up police stations, street safe surveys and social media.

But we found that methodology in the plans wasn’t always clear. This is sometimes the case where there could potentially be language or cultural barriers to working with people. We found some plans that stated the force would engage with a particular section of the community only “as and when required”. This suggests that it would be in response to something having happened, rather than being done proactively. We encourage the force to review its plans for working with people to make sure that regular and continuing contact is taking place with harder-to-reach communities. This will help ensure that any language or cultural barriers can be understood and addressed at an early stage.

Partners from other organisations are involved in setting local priorities

The force has multi-agency local focus hubs in each of its territorial policing areas. Each month community analysts prepare community tasking documents, which help the hubs understand the crime and anti-social behaviour problems affecting the local area, and identify hotspot locations and repeat victims. The tasking document is presented at a monthly meeting between the force and other relevant organisations, to agree the priorities for the following month.

We observed local focus hub meetings, which were well attended by partners from other organisations. All parties actively contribute to the discussions on what the monthly focus and priorities should be. All organisations also take responsibility for leading on the areas they are responsible for. This is positive, as local priorities are determined in consultation and are informed by a wider range of data and information than simply police data. This produces a much richer picture of information.

The force is taking active steps to be more visible in communities

The force covers a large geographical area, which can make it difficult for officers and staff to maintain visibility in some rural communities. Because of this, the force has developed a rural policing model so it can provide a police presence in some of its more remote areas. We found an example of this in Millom, where the force is using office space in a fire station as a base, as there is no longer a police station in the area. This means that rural communities have an opportunity to meet with the police and are more likely to feel that they are valued by the force as a result.

In some areas of the force, PCSOs use the hashtag #BackOnTheBeat to advertise when and where they are planning to visit on foot patrol. This is to encourage members of the community to come and speak with them. This is positive as it increases police visibility and gives people the opportunity to approach the police easily without having to be proactive in seeking them out.

The force is encouraging its communities to become involved in local activity so they can become more resilient

We found several examples of the force working with communities to help them become more resilient. In the Ormsgill area of Barrow-in-Furness, the force has been working with the community and other relevant organisations to develop the Ormsgill Stronger Together project. Funding was secured to reopen the community centre, and the community was encouraged to become involved and take responsibility for running it. The council provided a plot of land that had previously been used by drug dealers, and a community garden was developed. People from the local community interviewed and selected local artists who contributed to the project. Community members took responsibility for running community events such as a Halloween parade.

Residents have been exploring opportunities to turn the community hub into a profit-making venue that would benefit the local community. Local residents also felt empowered to develop a pop-up post office. This means that people no longer have to travel into town to access postal services. This work is positive as it shows what can be achieved when the police, other organisations and communities come together to tackle local issues.

The force makes effective use of volunteers to help tackle crime and anti-social behaviour

The force has a police cadet programme in place. It is also one of 17 forces in England and Wales that has a Mini Police scheme. The Mini Police scheme is aimed at children of primary-school age. Mini Police officers are given training by PCSOs on important issues, which they then cascade to their peers in school assemblies. Examples include anti-social behaviour, water safety, county lines and child sexual exploitation.

Police cadets carry out community activity to help resolve local issues, for example, litter picking. They also support local events such as marshalling at Park Runs and supporting Remembrance Sunday parades.

Mini Police and police cadets are also a useful resource as part of the force’s plan for working with people. They act as role models to peers and family members, which helps build positive relationships with local communities. The work the force is doing in this area is important as it also provides opportunities for young people to help build their resilience and develop valuable life skills.

The force should ensure effective external scrutiny of its use of stop and search powers, and use of force

During our last inspection the force was issued with two areas for improvement (AFIs) about the need to develop external scrutiny arrangements for stop and search, and the use of force. The force has recently established external scrutiny arrangements through its independent advisory group (IAG), which looks at stop and search, use of force, and hate crime. The meetings are independently chaired and the agenda for scrutiny is consistent throughout all the territorial policing areas. These arrangements are in the early stages of development and the force recognises that there are still gaps that need to be filled to make sure there is more diverse representation and active membership.

We found that scrutiny within the panels was inconsistent. It is often focused on members questioning police processes, rather than on effective scrutiny in things like the application of GOWISELY or reasonable grounds. While the force has made some progress in its external scrutiny of stop and search, and use of force, the arrangements aren’t yet well established. Therefore, both AFIs will remain in place and progress will be monitored as part of the PEEL continuous assessment programme.

Adequate

Preventing crime and anti-social behaviour

Cumbria Constabulary is adequate at prevention and deterrence.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to prevention and deterrence.

The force works effectively with a range of other organisations in problem‑solving, crime prevention and early intervention

Cumbria Constabulary has developed integrated ways of working with other organisations through its local focus hubs. There are six hubs that are aligned with local district councils. The hubs comprise a range of organisations including local authorities, health services, the fire and rescue service, voluntary and charity organisations, and youth-based services. The benefits of effective collaboration are clear, and we found strong evidence of well-established ways of working together between these organisations and strong commitment from the force to ensure it was effective.

We found that tasking processes with other organisations appeared to work effectively. Partners in the hubs are involved in helping to set local priorities and work together to solve local problems. When one of the partners in the hub feels that a local issue would benefit from multi-agency problem-solving, they make a referral to the hub. Local focus hubs have adopted the OSARA (objective, scanning, analysis, response and assessment) problem-solving model. All referrers are required to outline the end result they are seeking to achieve when making the referral. This is a good way of working as it shows how the force works with other relevant organisations in joint problem-solving using a structured model.

The force has dedicated problem-solving PCs in each of the hubs. Problem-solving referrals are received in the hub and categorised using a scoring system that determines the level of risk. When a referral is scored and accepted, an automatic Microsoft Teams problem-solving profile is generated that can be accessed by all partners involved in the project. Activity carried out as part of the project is recorded on the problem-solving profile. This includes sharing of outcomes and good ways of working. Using Microsoft Teams in this way is positive as it means that activity is accessible to all parties involved in dealing with the same problem, and everybody can contribute.

We found many examples of the force working effectively with local focus hub partners and communities to solve local problems. An example of this was in Workington, where tensions had developed between a traveller encampment and the settled traveller community. The force declared a critical incident and a multi-agency plan was developed to solve the problem. The plan included the use of Remedi, a restorative justice practitioner. The force later provided feedback to the community under the principles of ‘you said, we did’. Providing feedback in this way is important as it will give communities confidence that when they report matters of concern they will be listened to, and meaningful action will be taken.

The force is developing improved local governance arrangements for reviewing its neighbourhood policing performance

The force has recently established neighbourhood policing performance review meetings in each policing area. At the time of inspecting, the arrangements were new and evolving. We found that the meetings weren’t supported by meaningful performance information or analysis linked to neighbourhood crime problems. The local focus hubs have a performance framework in place, but it measures outputs rather than end results. It is currently under review. The lack of an effective performance framework means the force isn’t able to fully understand the impact of its neighbourhood policing activity.

We are reassured by the force’s plans to increase its strategic and performance analytical resources. This will provide the opportunity for more effective analysis of neighbourhood team performance. We comment on this further in the ‘Strategic planning, organisational management and value for money’ section of this report.

The force has a strong focus on early intervention

The force has an Early Help strategy in place and is committed to early intervention to help prevent young people being drawn into criminality or suffering adverse childhood experiences. Early intervention will also reduce future demand for neighbourhood policing services. The local focus hubs are supported in their work by child-centred policing teams who are central to the force’s early intervention work.

The teams were developed because the force recognised there was a gap in service provision where children and young people didn’t meet the children’s social care threshold for Early Help. Children and young people can be referred to the child‑centred policing teams by any agency. They are assessed and prioritised using a range of risk indicators. The force told us that between July 2020 and October 2021, 1,485 young people who wouldn’t have met the threshold for Early Help were referred to the child-centred policing teams for support and intervention. There are low numbers of repeat referrals. The child-centred policing teams are a model of good work.

We found several positive examples of the early intervention work the force was carrying out. The Future Pathways programme is a good example of this. The ten‑week programme is carried out with children and young people in schools. It is designed to support learning up to the point where young people gain employment. The young people are involved in a range of confidence and team‑building activities, and are also encouraged to take part in a citizenship day in their local community. The programme is a good way of working as it is helping young people to build resilience, self-esteem and life skills.

The force is achieving results through its evidence-based policing methodology, but activity could be better co-ordinated, and the results and learning shared more effectively to help support learning

The force has an evidence-based policing (EBP) champion in place who leads some of the more significant EBP research in the force. They also act as a single point of contact for people seeking advice on EBP approaches. The force is part of the N8 Policing Research Partnership and has carried out several pieces of research through this partnership. One example is research about child-on-parent violence, which resulted in the commissioning of the Step-Up youth violence charity.

The culture of EBP is positive in the force, and we found numerous examples of successful projects and research; for example, the work done by the EBP champion to improve quality, timeliness, and overall standards of investigations. The EBP champion carried out initial research about how people make decisions in investigations, and researched models used by the military to understand how people communicated. Consultation exercises about investigative quality were designed so the force could establish evidence that included the views of practitioners. A deliberative enquiry group was developed to consult the evidence and determine what a quality investigation should look like. A set of investigative principles were then drafted, which appear to be driving improvements in quality.

The EBP champion role seems to be pivotal in advancing and supporting EBP activity. But there is no formal structure for co-ordinating the activity to make sure that learning is shared. This means the force may not always be clear on what activity is being undertaken, or whether it supports force objectives. The force may also be missing opportunities to share and learn from good ways of working. The force may wish to consider how it could better co-ordinate and track its evidence-based policing activity.

The force is professionalising prevention within neighbourhood policing through training, accreditation and continuing professional development

The force has improved the training provision for neighbourhood officers and staff since we last inspected. PCSOs have received crime prevention training. PCs and PCSOs have undertaken level 2 accredited problem-solving training, and sergeants and inspectors have done level 3 training through the Police Crime Prevention Academy. This is a good way of working as it means the force is investing in officer and staff development, so they have the right skills to carry out their role effectively.

Special Constabulary numbers are declining year on year throughout the force

The number of special constables in the force peaked on 31 March 2012, when it had 174 in post. Since then, the number of special constables has declined steadily each year and by March 2021 it had fallen to 52. The force has a recruitment plan targeted specifically at people aged 30 and over. This is to attract ‘career’ special constables rather than those who join as a route to becoming a regular constable. The force is reviewing its recruitment plan for 2022 because it is likely that the implementation of the special constable learning programme (part of the Policing Education Qualifications Framework for all officers and staff), will also affect future recruitment. Special constables are a valuable resource, and we are reassured by the force’s continued effort to boost its volunteer workforce. We will monitor progress as part of our PEEL continuous assessment work.

Adequate

Responding to the public

Cumbria Constabulary is adequate at responding to the public.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force responds to the public.

The force undertakes a structured risk assessment when responding to calls for service, but it isn’t always consistently applied

We found that, overall, the standard of call handling was good. Accurate incident logs reflect the details of calls. In almost all the cases we looked at during our victim service assessment, a structured initial triage process (THRIVESC) had been undertaken and was clearly recorded on the incident log.

But we found during reality testing that sometimes THRIVESC assessments lacked detail, suggesting that THRIVESC wasn’t always understood by the call handler. We found that some officers and staff working in the contact management centre hadn’t had recent training in applying THRIVESC. While the officers appeared to be experienced and could explain their understanding of vulnerability well, the force would benefit from reviewing its THRIVESC training and testing the workforce’s understanding. This will mean the force is making sure that risk is being appropriately identified at the first point of contact so that vulnerable victims can get the right level of support.

We found that, in most cases, checks had been made to establish whether a caller was a repeat victim. When repeat victims are identified, call handlers record this on the incident log on most occasions. This means that most callers who are repeat victims are being identified and are therefore likely to receive appropriate levels of service.

Vulnerability, following the national definition, is being identified in most cases. In almost all the cases we looked at, we found evidence of checks being carried out to establish if the caller was vulnerable. Where vulnerability is identified, this is recorded in almost all cases. This is important as it means the force can take appropriate safeguarding opportunities to support vulnerable victims when they are identified. In most of the relevant cases we looked at, there was evidence of the identification of vulnerability of people other than the caller, for example, witnesses or other people in the household. This is positive as it demonstrates that the force is identifying vulnerability more widely than might be initially obvious at first point of contact.

The force has clear processes to recognise and record vulnerability and we were reassured to find that in nearly every case we looked at, the prioritisation and response to the call for service was appropriate to the nature of the caller and incident.

The force has introduced a new incident management system called SAFE. This is designed to improve integration with other systems; for example, it enables automated Police National Computer checks when a person’s details are entered. SAFE has been modified to improve the early identification of victims.

The force seeks advice from expert practitioners to better inform decision-making and risk assessments

The force has a well-established single-point-of-access (SPA) telephone line in place. This is a joint activity with Cumbria County Council mental health services that allows staff to get expert and timely advice from professionals when dealing with people in mental health crisis.

The force is also part of the Cumbria Mental Health Concordat, which includes various public and third-sector organisations, and works to improve the quality of mental health provision.

Officers are able to respond to urgent incidents quickly enough to secure evidence and safeguard victims

We found that response officers were usually able to respond to incidents quickly enough to secure scenes, safeguard and provide a quality service. Emergency incidents are always responded to quickly, and this is also usually the case with grade 2 priority incidents. Most people we spoke to felt that they could usually attend incidents on time and that their response had improved because they were now able to patrol rural areas in vans rather than cars. This means they can transport prisoners easily from scenes without having to wait for other vehicles to assist.

The force has a diary appointments system to help it manage demand. We found that, generally, members of staff who are allocated to ‘diary car’ duties are ring fenced so the force can keep appointments. Any decision to remove an officer from the diary car must be authorised by the force incident manager or duty inspector. This is positive as it means that appointments aren’t being routinely rescheduled, and members of the public aren’t being let down through delays in response.

The constabulary understands demand within its contact management and response functions, along with the resources required to meet this demand

The force has undertaken work to understand demand, and this is reflected in the force management statement. Using the patrol allocation model (PAM) the force can understand demand and allocate resources accordingly. The model analyses incidents by type and assesses how long on average each incident takes to resolve. The force also carries out ‘day in the life of’ assessments. The findings of this analysis allow the force to carry out modelling to assess how many resources are required and where they are most needed. It was this approach that determined the current shift pattern throughout Cumbria Constabulary.

The PAM is periodically refreshed; however, a full demand review wasn’t carried out during the COVID-19 pandemic as the force felt it wouldn’t provide an accurate assessment of true demand. We comment further on this in the ‘Strategic planning, organisational management and value for money’ section of this report.

The force has a good understanding of its mental health demand and is making effective use of mental health street triage

The force told us that mental health demand rose by 35 percent between 2016 and 2021. It is predicted to rise by a further 24 percent by 2024. To help the force reduce its mental health demand, it has been working with partners in Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust to pilot a mental health street triage team in the north territorial policing area. We found that most people spoke with enthusiasm about the mental health street triage service.

The pilot has been evaluated internally by the force. The evaluation suggests the pilot has proved successful in preventing 86 detentions under section 136 of the Mental Health Act. It has also saved almost £50,000 of police officer time. The force has since implemented mental health street triage in the south territorial policing area. At the time of inspecting, discussions were being held with mental health partners to roll it out across the rest of the force. The work of the mental health street triage is positive as it means that people in mental health crisis can access appropriate support quickly, at the same time as reducing the demand on the force.

Through changes to its contact management operating model, the force has increased the number of incidents it can resolve without deployment

Cumbria Constabulary is responsible for policing a substantial geographical area. Much of this area is rural and this can make it difficult to respond to some incidents in a timely manner. The force recognised this and has changed the operating model in its contact management centre to increase the number of calls that are resolved without deployment. The force places police officers in call handler roles, and this helps reduce response demand.

The force told us the proportion of incidents resolved by call handling staff increased from 20.7 percent in 2013 to 37.7 percent in 2020. This is positive but must be balanced against the impact that the operating model is having on call handling times and abandonment rates, as outlined in our areas for improvement in this section. The force is planning to review the operating model to determine whether it is lasting in its current form. This is positive as it is important that the force can demonstrate a responsive service throughout all areas, and not just with a focus on early resolution.

The energy of response officers has been affected due to exceptional operational policing demand, particularly during the summer of 2021

The force’s area of operation has a large transient population. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, more than 47 million tourists visited the Lake District in 2019. At the end of each COVID-19 lockdown, the Lake District experienced unusually high spikes in tourism demand. The annual Appleby Horse Fair was also rescheduled from June to August – the peak of the summer holiday season. Coupled with the need to police several protests during this time, these factors combined to create an exceptional set of circumstances. This has significantly increased frontline demand. The force had no option other than to cancel response officers’ rest days at times so that it could manage this demand. This also meant that staff were often abstracted from neighbourhood policing roles throughout the year to support frontline policing.

At the beginning of our inspection, response team officers told us they had faced unprecedented demands for service over a prolonged period. They were tired. But they also described a sense of pride in belonging to the constabulary, and a desire to continue providing a good service to the people of Cumbria. There was also some recognition that their immediate supervisors and senior leaders cared about their wellbeing. We are reassured that the constabulary provides a wide range of supportive and preventative wellbeing measures, and that senior leaders are mindful of the pressures faced by the workforce over the past year.

Adequate

Investigating crime

Cumbria Constabulary is good at investigating crime.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force investigates crime.

The force has established governance and scrutiny in place in relation to investigative standards, which is bringing about improvements

The force’s Keep Me Safe standards document outlines what it expects of the workforce in relation to investigative standards. The investigative standards board provides oversight of the force’s criminal investigations performance and is responsible for governance at a strategic and operational level.

The force has developed a set of investigative principles, spelled out in mnemonics to help investigators easily recall each important stage of an investigation. The mnemonics given to investigators cover several important areas: the initial investigation plan; initial supervisory review; handover to specialist investigators; supervisory review and investigation updates; and final review and closure of the investigation. The principles are well understood by investigators. The force has been monitoring compliance with the investigative principles and has found that investigative standards have improved. This was also evident during our crime file review where we found that, overall, there were good standards of investigation.

We found effective and timely investigations had been carried out in most cases we looked at. Crimes were usually allocated to the most appropriate team for investigation. We also found clear evidence of supervisory oversight of continuing investigations in most of the cases we looked at.

We found evidence of proportionate investigations with appropriate investigative opportunities undertaken in line with force policy in most cases we looked at. This is positive as it means that communities of Cumbria can have confidence that crimes reported to the force will be investigated effectively.

The force performs well when compared to most other England and Wales forces in relation to charge and summons rates for victim-based crime, and overall crime outcomes

The force had the third highest charge/summons rate for victim-based crime in England and Wales for offences recorded in the year ending 31 March 2021 (9.9 percent). It also had the fifth highest adult caution rate (1.4 percent), and the sixth highest community resolution rate (2.8 percent).

The force also had the fifth highest charge and summons rate for overall sexual offences (6.2 percent). For all these outcomes, Cumbria Constabulary had a higher than expected rate compared to other forces.

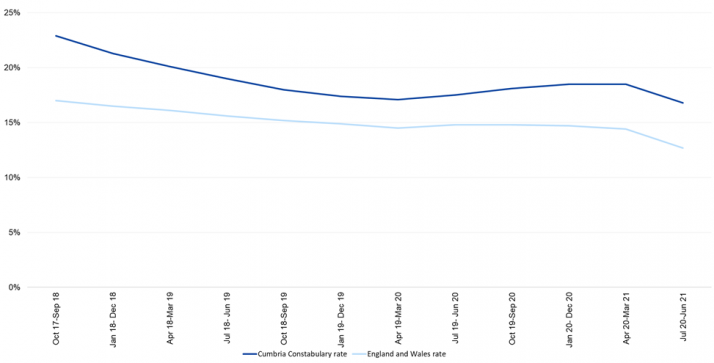

For offences recorded between 1 October 2017 and 30 June 2021, the force consistently had a higher combined ‘action taken’ outcome rate when compared with the England and Wales rate. For offences recorded in the year ending 30 June 2021, the force’s ‘action taken’ outcome rate was 16.8 percent compared to the England and Wales rate of 12.7 percent.

The data is positive as it means that victims who report crime to Cumbria Constabulary are more likely to receive a positive outcome than in most other areas of England and Wales.

Combined ‘action taken’ outcome rate for offences recorded from year ending 30 September 2018 to year ending 30 June 2021; Cumbria Constabulary vs England and Wales

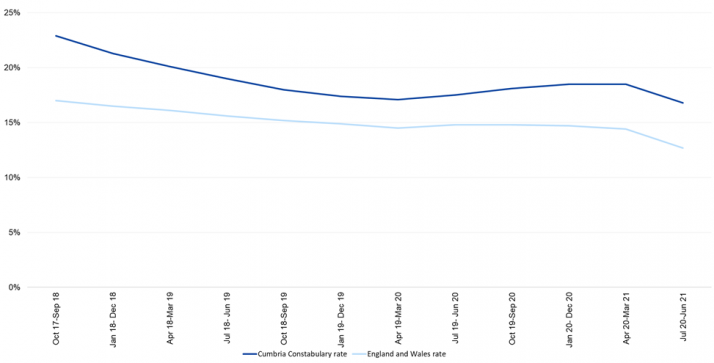

The force is experiencing declining performance in its rape charge rates

For rape offences recorded in the year ending 30 June 2021, the proportion where the offender was charged fell to 1.9 percent compared with 7.2 percent in the year ending September 2018. This is a substantial decrease of 5.3 percentage points.

The England and Wales rape charge rate also decreased over the same period, but not at the same rate as seen in Cumbria Constabulary. The England and Wales charge rate decreased from 4.3 percent to 1.7 percent (2.6 percentage points) over the same period.

The force has one of the lowest rape attrition rates nationally; however, while this is positive, there is more that can be done.

The force must do more in working together with other criminal justice organisations to make sure that victims who report rape in Cumbria aren’t let down by the criminal justice system. But we are reassured that important work is being done to improve performance in this area. There is a rape investigation improvement plan in place that is linked to the Violence Against Women and Girls strategy and the National Rape Action Plan. We will monitor progress against this as part of our PEEL continuous assessment work.

Charge/summonsed rates for rape offences recorded from year ending 30 September 2018 to year ending 30 June 2021; Cumbria Constabulary vs England and Wales

The force has a good understanding of its crime demand and of the resources it needs to manage the demand effectively

The force has combined its investigative resources into crime and safeguarding teams (CAST). The force understands its current CAST demand and the factors that will influence future demand. This understanding is reflected in the force management statement, which contains predictions of crime and safeguarding demand up to 2023.

The force is making good progress in recruiting detectives through its detective Degree Holder Entry Programme (DHEP)

The force has developed bespoke investigation pathway training in its crime academy for detectives recruited through DHEP, and it is in the second year of recruitment. The first cohort of 16 students was recruited in April 2020. The programme is modular and is run over three years.

The force is in a good position when compared to many other forces in England and Wales that are still in varying stages of development. The establishment of the programme is a good way of working as it means the force is being proactive in developing investigator resilience.

The digital forensics unit provides support for the most serious and high-harm crimes, but there are delays for less-serious crimes

We found that demand in the digital forensics unit was being managed, and backlogs of devices awaiting examination were gradually reducing. Queues are prioritised according to risk, and the team provides good support for the most serious or high‑harm crimes. But we found there were often long delays in examining mobile phones for less serious offences. This means that investigators are sometimes unable to progress investigations, and this could lead to victims disengaging.

We are reassured that the force has been contracting out some of its examinations to an external provider to reduce backlogs. The force has also invested £170,000 to enhance some of its in-house technical capabilities and has increased the number of digital forensics examiners. But the force must maintain focus in this area to reduce delays so that investigations can be taken forward in a timely manner

Good

Protecting vulnerable people

Cumbria Constabulary is good at protecting vulnerable people.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force protects vulnerable people.

The force has a clear focus on keeping people safe and protecting vulnerable people

The force’s overarching plan in relation to vulnerability is the Safeguarding Excellence Plan 2020–2022, which has seven strands: safeguarding; early intervention and prevention; access to services; public health and policing; investigative standards; offender management; and support and intervention. Keeping people safe is a clear priority for the force. Without exception, everybody we spoke to understood the importance of vulnerability.

The force is developing consistent operational governance and scrutiny in relation to vulnerability

The force vulnerability board provides governance in relation to the control strategy priority of vulnerability. But we found the purpose of the board’s meeting was unclear as the board appeared to combine strategic and operational areas of business. This means the effectiveness of discussions is diluted. We also found that discussions held about repeat victims and offenders were sometimes duplicated in other meetings that we observed. The force recognises that this is an area for development and is reviewing its operational governance arrangements to make sure they are fit for purpose. We are reassured by this.

The force analyses patterns of offending against the vulnerable and has effective processes in place to identify and manage repeat victims and offenders

The force has systems in place to identify repeat victims and perpetrators. The top ten domestic abuse victims in each territorial policing area are identified and allocated to safeguarding team officers for safeguarding support and advice.

Operation DART (domestic abuse reduction tactic) and Operation CERT (child exploitation reduction tactic) are the force’s response to repeat domestic abuse and child exploitation offenders. Bespoke ‘four Ps’ plans (pursue, prevent, protect, prepare) are developed for each person and uploaded onto the Red Sigma system, which is the force’s intelligence, tasking, and briefing database. Once profiles have been uploaded, they are accessible to anybody working in the force. This is positive as it means the workforce can easily find information about vulnerable people in their local policing area, or about people who pose a risk. This also means that activity assigned to officers or staff can be easily viewed and tracked.

The force recently introduced a child exploitation risk assessment and review (CERAR) process that builds on already well-established multi-agency arrangements. The local authority leads on the arrangements and has appointed a children’s social care team manager to co-ordinate the activity. Children at risk are identified, scored and tracked using the exploitation vulnerability tracker. Internally, activity is monitored through the county lines and organised exploitation meeting. The local authority CERAR co-ordinator co-ordinates the management of children at risk of exploitation. Low-risk children are managed by the local authority, and medium-risk and high-risk children are managed by crime and safeguarding teams. This is positive as it frees police resources to focus on higher-risk children while still making sure that children receive appropriate support.

The force is taking positive action when dealing with domestic abuse, and this is having a favourable impact on conviction rates

The force performs well nationally in relation to domestic abuse conviction rates. Data supplied by the Crown Prosecution Service indicates that over the past 12 months, the force has consistently had one of the highest domestic abuse conviction rates in England and Wales.

Since the year ending 30 June 2018, the force has had consistently higher domestic abuse arrest rates when compared with the England and Wales rate. The domestic abuse arrest rate was 40 percent for the year ending 30 March 2021. This is higher than the rate for England and Wales as a whole, which was 29 percent for the same period. When supported by the force’s encouraging performance on domestic abuse conviction rates, this suggests there is a tangible link between positive action taken at domestic abuse related incidents and higher conviction rates.

While Cumbria Constabulary is performing well when compared to other forces, there is a national ‘direction for improvement’ in place about domestic abuse proactivity, including arrest and conviction rates.

Domestic abuse arrest rates between years ending 30 June 2018 and 31 March 2021; Cumbria Constabulary vs England and Wales

The safeguarding help desk in the command and control room is a model of good work, but it could be more effective in supporting the frontline response

The force has a well-established safeguarding help desk in its command and control room. Staff members screen all live logs from the SAFE incident management system, and sometimes record guidance on the log for the attending officer. The help desk also provides a useful way of checking for compliance with crime recording principles. But we found staff working on the help desk didn’t appear to provide real-time support or guidance to response officers on duty and didn’t have access to radios.

Most response officers we spoke to said that while the information recorded on the log was sometimes useful, the desk didn’t provide direct support at incidents. This means that response officers aren’t using the specialist advice available that could better inform decision-making at incidents. The force may wish to consider reviewing the help desk operating model so that it can maximise the resources to provide more effective support at the front line.

The force has adopted a child-centred approach to policing of incidents involving children and young people

The force has developed youth crime management procedures. Any recorded crime where the suspect is a child or young person can’t be closed until it has been reviewed by a member of the child-centred policing team. This is usually an officer seconded to the Youth Offending Service but co-located with the child-centred policing team. In any instance where a child has been brought into custody, the arresting officer must complete a safeguarding referral form (SAF). Where there is a potential for a criminal justice outcome to the crime, the Youth Decision-Making Panel meets to agree the most appropriate outcome for the young person, with a focus on not criminalising them if it can be avoided.

Officers in the child-centred policing team also carry out community resolution work with young people. The officers spend time with the young person, guiding them through an educational workbook as the officer discusses the offence and the consequences of the young person’s behaviour. The work is positive as it means that the force is avoiding criminalising young people and is improving their life chances.

The force has processes in place in the safeguarding referral unit to risk-assess and pass on information about vulnerable people who may be at risk, but the amount of research carried out affects the timeliness of decision-making

When a member of staff has a concern about a vulnerable child, they submit an SAF. The safeguarding referral unit carries out screening and processing of SAF forms. Members of staff in the unit have access to Liquid Logic (the local authority children’s social care database). They use this system to carry out research to help them decide whether the referral reaches agreed thresholds for sharing with local children’s social care. Once the research is completed, a summary of the information held on Liquid Logic is added to the SAF, and then a single-agency police decision is made about whether the information meets the threshold. If it does, then it is shared with children’s social care. While the work done by the safeguarding referral unit is reducing demand on children’s social care, this means that when the force provides the SAF to partners in children’s social care, they are essentially giving them a summary of their own information.

The amount of research the unit is undertaking is also affecting the timeliness of decision-making. On the day of inspecting there were 247 SAFs awaiting a decision. While we are reassured that there is a process in place to make sure that any risk is managed, the queues of SAFs awaiting decisions mean that delays in information sharing are likely. As a result, vulnerable people may not be able to access support in a timely way. The force has recognised that this is a potential problem and plans to review its processes. We are encouraged as this will make sure it is operating efficiently, and so delays in decision-making are reduced.

Good

Managing offenders and suspects

Cumbria Constabulary is outstanding at managing offenders and suspects.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force manages offenders and suspects.

The force uses nationally recognised risk assessment tools, and these are completed in a timely way

The force uses the nationally recognised offender management tool ARMS (active risk management system). Bespoke risk management plans are created for each offender. We found that visits to offenders were based on the offender manager’s assessment of the risk posed by the offender. ARMs are reviewed on an annual basis, as well as when there is a significant change. Risk management plans are completed in line with ARMS assessments, which supports the force in mitigating risk.

We found that the force was aware of recent changes to authorised professional practice (APP) and it was clear that those managing sexual or violent offender (MOSOVO) teams were aware of national guidance. We found that all staff had been trained in APP and that continued professional development was a priority. This is positive as it means offender managers can keep up to date with changes to working practices.

The force continued to manage registered sex offenders effectively during the pandemic

During the COVID-19 lockdown the force continued to visit all high-risk and medium‑risk offenders. Offender managers identified any offenders who had pre‑existing medical conditions that may have made them vulnerable. If a decision was taken not to carry out a visit, alternative methods were used to gather information on the offender, such as using family members. Officers were provided with PPE kit, were vaccinated early and had regular briefings from line managers about changes to policy and legislation. This is positive practice as it means that the force was able to continue managing the highest-harm offenders during COVID-19.

Management of offenders, including reactive management of offenders, is in line with APP

The force doesn’t deviate from APP, and we found that there was a good knowledge of it among operational staff. This is demonstrated in many areas including the double‑crewed visit regime, clear use of the police national database and adherence to multi-agency public protection principles.

The resourcing of the MOSOVO department allows the force to take a proactive approach to offender management, and this is well led and supported by supervisors. Officers are encouraged to have professional curiosity, and prior to an offender visit they pre-arm themselves with a range of information. This includes automatic number plate recognition checks, Police National Computer information, and local intelligence. We found that offender managers clearly took pride in their work and were tenacious and passionate about investing in safeguarding in their communities.

The force has one approved premises that specifically houses registered sex offenders. This produces a large volume of high-risk work that is often time-critical because of the urgent placement of high-risk subjects. It is also located near a town centre. This increases the risk and urgency of action to be taken when offenders are housed at short notice. Consideration is being given to allocating a designated offender manager to the approved premises and, in our view, this would be a positive development.

Neighbourhood and response teams are aware of registered sex offenders in their area. The awareness is sufficient that they recognise opportunities, take enforcement action, submit intelligence and safeguard victims

The team have an extremely positive and proactive relationship with neighbourhood officers. The MOSOVO officers value their neighbourhood colleagues highly. This was clear from the specific examples they gave of when effective information sharing and appropriate action from frontline officers had led to the identification of further offences and, ultimately, safeguarding.

The force has systems in place to proactively identify from all sources the sharing of indecent images of children

The force has effective digital capacity and capability to support MOSOVO teams. The teams have access to polygraph tests, Magnet Outrider software, the Compass discovery tool and eSafe. There is further support available from digital media investigators, the digital forensics unit (DFU) and the online child sexual abuse and exploitation (CSAE) team. We found there were effective processes in place to review eSafe data and act once a further offence was identified.

The force’s approach to the investigation of the sharing of indecent images has recently undergone a root-and-branch review. This has led to an increase of staff, and the introduction of a weekly intelligence-led risk review process for outstanding warrants. There are ambitious and achievable plans to move to a ‘today’s business today’ approach to warrant execution once the intelligence picture has been finalised and a decision made on the type of action needed.

While the capability to review devices at the scene is limited and, as such, may increase the burden on the DFU, there is positive and regular discussion about risk and prioritisation.

Information sharing for safeguarding purposes mainly takes place after the warrant has been executed, but progress is being made to formalise an agreement with children’s social care to do this earlier in the process for the future.

Cloud storage retrieval is an emerging national problem for online child abuse investigation teams. The force recognises this and is working with an external provider to develop a long-term solution. The proactive approach of the force is positive.

The wellbeing of officers and staff working in MOSOVO and online CSAE teams is a priority for the force

Wellbeing is a priority for teams working in MOSOVO. All staff we spoke to were extremely positive about their role and their development opportunities. They felt valued and well supported, and their job satisfaction was clear. The workforce has access to psychological assessment and quarterly team days. Welfare is discussed at monthly one-to-one sessions, and the teams felt supported and valued by their supervisors.

We found that staff members were motivated by a dedication to their role. But it is also apparent that they feel valued and enthused because of the investment the force has made in their area of work. They feel the force listens to them, and that they are equipped in terms of digital support to allow them to carry out their roles effectively. A strong team ethic and supportive environment appear to have grown from this.

The force has invested in the wellbeing of MOSOVO teams by working with an external provider to hold a ‘safeguarding the safeguarders’ event. This was to provide the workforce with self-care tools to help them become more resilient through a focus on neuroscience. This is positive as it means that staff members will be better able to manage their own wellbeing while working in such a high-risk specialist area.

A ‘burn-out resilience plan’ for the department is currently in the development stages. It is hoped that this will help retain skills and experience in the wider specialist capabilities team by allowing staff to rotate through the more demanding aspects of the role to less stressful duties and introducing a tenure for the online CSAE team.

The force is making good progress towards implementing a new integrated offender management (IOM) model in line with the Neighbourhood Crime IOM Strategy

The force has a well-established and effective IOM programme in which it works together with other organisations. IOM works by diverting prolific offenders away from committing crime by addressing the root causes of their offending. The force uses the probation service offender group reconviction scale (OGRS) to assess the likelihood of offenders reoffending. This helps the force decide which offenders to select for the IOM programme. OGRS is supported by a crime severity score that also considers the harm caused by the offender.

The force is working with the health service and the national probation service to move to new IOM ways of working as part of the new Neighbourhood Crime IOM Strategy. The work is being directed by a multi-agency steering group. This is positive as it will provide more clarity and governance to this important work, and will put neighbourhood crime prevention at the centre of the force’s IOM approach.

The force understands the benefits and end results of managing offenders effectively, as well as the impact and costs associated with offenders

The force has adopted IDIOM to assess the cost benefits of managing offenders through IOM. IDIOM is a web-based offender tracking tool provided by the Home Office to support IOM arrangements. The force has been using it for several months, and early data is already suggesting that it is having a positive impact in terms of the crime cost to society (using the crime severity score as a guide).

But there are some early challenges in administering the IDIOM system, as it currently relies on offender managers to input information. This means that the time spent administering the system could potentially reduce the time offender managers have available to work with offenders. We encourage the force to consider how it could provide administrative support to offender managers in the use of IDIOM to reduce the impact on their operational role.

Outstanding

Disrupting serious organised crime

Cumbria Constabulary requires improvement at tackling serious and organised crime.

Understanding SOC and setting priorities to tackle it

The constabulary has introduced a process to manage SOC priorities

In September 2022, the constabulary completed a strategic assessment identifying SOC as a priority. There is also a separate SOC strategy that outlines how SOC threats, such as serious theft and drug supply, will be tackled using a 4P structure. However, we were concerned that the lack of analytical staff explained in the area for improvement above, may limit the constabulary’s ability to monitor performance and identify any emerging threats.

The constabulary is now using the MoRiLE assessment model to assess SOC threats. However, this hasn’t yet been applied to every SOC threat identified. The constabulary should complete this process as soon as it can.

The constabulary uses several meetings to co-ordinate its response to SOC. Every two weeks, the intelligence assessment response meeting reviews current intelligence and the management of OCGs. It also decides how to allocate resources. A meeting to consider individual OCGs has recently been reintroduced. However, senior officers accept that they need greater involvement of SOC partners for this meeting to become effective.

Resources and skills

LROs have received training but need continuing support

The constabulary generally appoints detective inspectors from local policing teams to the role of LRO. At the time of our inspection, training had recently been provided to LROs. We welcome the introduction of this training. During our inspection, we saw little evidence that LROs are supported with continuing professional development. We have since been reassured that this will be in place later in 2023.

LROs can access tactical advice on covert techniques from SOC specialists. However, this is on an informal basis. Some LROs explained to us that competing demands mean they struggle at times to dedicate enough time to SOC.

The constabulary has a roads crime unit targeting SOC activity

Since 2022, the roads crime unit has successfully recovered over £2 million in cash and illegal drugs. The unit has four officers who work to identify and intercept vehicles suspected of being involved in SOC. However, like the personnel in the economic crime unit, they get little analytical support and must analyse their own data.

The constabulary should increase its capacity to proactively tackle SOC at a local level

The constabulary has a dedicated SOC unit to investigate OCGs that pose the highest level of threat. We found that the personnel in the unit were experienced and appropriately trained to carry out specialist covert investigations.

However, in comparison, we found that the resourcing of local proactive teams was challenging. During interviews and focus groups, we heard that in some areas there aren’t enough officers to carry out the investigations that are referred to these teams. We also found that some local teams were generating and working on tasks that were outside the tasking process. This process should identify constabulary priorities to make sure resources are used efficiently and effectively. If tasking teams work outside this process, it may mean that SOC threats aren’t investigated at an appropriate level.

Tackling SOC and safeguarding people and communities

Changes to local government structures in Cumbria have affected SOC partnership working

On 1 April 2023, local government arrangements in Cumbria changed. Cumbria County Council and the six district councils were replaced by two unitary authorities.

During our inspection, we were told that the new arrangements have led to some uncertainty and adversely affected partnership working arrangements. This is largely outside the constabulary’s control and has affected other partners, such as health and probation services.

The constabulary has tried to mitigate this by establishing a partnership board to develop information sharing and partnership working. The group includes representatives from several organisations, including children’s social care, adult social care, the local authority and HMPPS. At the time of our inspection, this process was new, so we were unable to assess its effectiveness.

The constabulary aims to prevent people from becoming involved in SOC and protect vulnerable victims

Child-centred policing teams have been established in each local policing area. Specially trained officers work with children and their parents at home and in school. The teams work with partners, including local authority child safeguarding teams and children’s care homes. They use a range of diversions and interventions intended to divert children from criminal activity. For example, the PCC has made funding available for officers to work with the RISE project, which is an early intervention mentoring service provided by Barnardo’s that aims to help those aged 10–17 to make positive life choices.

We were also told that the constabulary:

- works closely with Barrow Football Club to prevent young people from getting involved in football violence;

- raises awareness about cybercrime in schools through local officers or police community support officers by giving presentations that reach as many as 600 children and parents a week; and

- appointed a financial abuse safeguarding officer in 2021 who has supported over 3,000 victims of fraud and recovered over £1 million.

The constabulary has invested in personnel to prevent people from becoming involved in SOC

The constabulary has funded several posts focused on preventing SOC offending and victimisation linked to vulnerability. This includes:

- a prevent co-ordinator whose role requires expertise in the application and management of ancillary orders to prevent reoffending; and

- a county lines co-ordinator who works with partners to divert vulnerable people away from this type of criminality.

Analysis of disruption data for the year ending 31 December 2022 shows that the constabulary had the highest proportion of prevent disruptions (30 percent) when compared to other forces in the region. This suggests that these roles are having a positive influence on preventing people from becoming involved in SOC.

Read An inspection of the north-west regional response to serious and organised crime – November 2023

Requires improvement

Building, supporting and protecting the workforce

Cumbria Constabulary is good at building and developing its workforce.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force builds and develops its workforce.

The force has an ethical and inclusive culture that promotes a sense of belonging

The force is working to make sure the workforce has a sense of belonging so that people feel included. We found there was a positive, supportive, and inclusive culture in the force. Without exception, everybody we spoke to said that they felt proud to work for Cumbria Constabulary.

The force has established an inclusion hub, which is a central repository containing information files where officers and staff can access advice on a range of subjects such as cancer, stammering, chronic illness, disability and menopause. The hub also provides the workforce with opportunities to connect with people who have lived experience of challenges they are facing themselves. We spoke to several staff members who described positive experiences of being able to access support on issues like autism and dyslexia. The inclusion hub is a good way of working as it is likely to have a positive impact on retention and progression.

The constabulary has a well-established fair passport scheme. The scheme supports people with a range of issues related to culture, religion, health, disability and gender. Once reasonable adjustments for a member of staff have been agreed, they are applied whenever that person moves into a different role. This is positive as it relieves the staff member of the need to repeat conversations with new line managers or have new assessments carried out every time there is a change in posting.

The force has a workforce exchange scheme in place to encourage serving members of staff from other forces to spend time working in Cumbria Constabulary. This is a good way of working as it is providing the opportunity to share learning and different perspectives between forces. It has also attracted people to apply to transfer to the constabulary when they might otherwise not have applied.

Cumbria Constabulary employs the highest proportion of female officers of any force in England and Wales. As of 31 March 2021, 40 percent of police officers in Cumbria were female

The chief constable is president of the British Association for Women in Policing and is making sure that the learning from undertaking this role is reflected in working practices in the force. The force uses the NPCC Workforce Representation Toolkit to help shape its internal work, including that related to gender. Forty percent of police officers in the force are female. This is the highest proportion of any force in England and Wales. This is positive as it demonstrates that the force is being proactive to make sure the workforce is representative of the communities that it serves.

There are opportunities for personal development and career progression, supported by a fair promotion process that was developed after consultation with the workforce

The promotion process has recently been revised as the force felt the previous process was outdated and time-consuming. The force worked with the Police Federation to consult staff, and then implemented positive changes. One of the changes was to provide an environment that was more relaxed and less intimidating for candidates, so that interviews were no longer held at the headquarters building. The force also developed arrangements to make sure that promotion panels had consistent membership throughout the interview process. Where people have been unsuccessful in the promotion process, the force is providing support with development plans. The changes are positive as they are likely to improve confidence in the promotion process and encourage people to apply for promotion.

The force’s wellbeing and occupational health provision is very effective and there are a broad range of preventative and supportive measures in place

The force has a strong focus on wellbeing, with a proactive occupational health unit (OHU) that provides a broad range of services. Most people spoke very highly of the OHU provision. OHU services are provided in house rather than being provided by another organisation, apart from specialists such as the force medical adviser and psychotherapy. The force also uses the services of health professionals in the community such as counsellors and physiotherapists. This is positive as it reduces the need for staff members to have to travel to force headquarters for appointments. The OHU is undertaking accreditation with the Safe Effective Quality Occupational Health Service and expects to be fully compliant by early 2022.

Cognitive behavioural therapy is also offered to the workforce. There is also an independent counselling service in place where six sessions are provided free of charge. We were told that staff could access this confidentially without needing a referral from their line manager. This is felt to be a positive arrangement and is likely to encourage people to make use of it to get the support that they need. OHU volunteers are provided with protected time to support the workforce.

The force has achieved the ‘Better Health at Work’ silver award and is working towards the gold award. This is positive as the award recognises the efforts of employers in addressing health issues in the workplace.

The force is taking effective action so that its workforce better reflects its communities

The force has a five-year positive action plan in place focused on recruitment, retention, progression, and getting local communities involved.

There is a dedicated positive action co-ordinator in post to support the recruitment, retention and career development of under-represented groups. We found clear and obvious encouragement from senior leaders.

Census data from 2011 showed that 1.5 percent of communities in Cumbria were of Black, Asian or minority ethnic origin. As of 31 March 2021, 1.0 percent of police officers in Cumbria Constabulary were from a Black, Asian and minority ethnic background. The force has set an initial target to increase this to 1.5 percent by March 2023 to make sure that its workforce reflects the community. But in the longer term the force is seeking to achieve workforce representation of 5 percent. This equates to around 65 police officers.