Overall summary

Our inspection assessed how good Warwickshire Police is in ten areas of policing. We make graded judgments in nine of these ten as follows:

We also inspected how effective a service Warwickshire Police gives to victims of crime. We don’t make a graded judgment in this overall area.

We set out our detailed findings about things the force is doing well and where the force should improve in the rest of this report.

Important changes to PEEL

In 2014, we introduced our police effectiveness, efficiency and legitimacy (PEEL) inspections, which assess the performance of all 43 police forces in England and Wales. Since then, we have been continuously adapting our approach and this year has seen the most significant changes yet.

We are moving to a more intelligence-led, continual assessment approach, rather than the annual PEEL inspections we used in previous years. For instance, we have integrated our rolling crime data integrity inspections into these PEEL assessments. Our PEEL victim service assessment will now include a crime data integrity element in at least every other assessment. We have also changed our approach to graded judgments. We now assess forces against the characteristics of good performance, set out in the PEEL Assessment Framework 2021/22, and we more clearly link our judgments to causes of concern and areas for improvement. We have also expanded our previous four-tier system of judgments to five tiers. As a result, we can state more precisely where we consider improvement is needed and highlight more effectively the best ways of doing things.

However, these changes mean that it isn’t possible to make direct comparisons between the grades awarded this year with those from previous PEEL inspections. A reduction in grade, particularly from good to adequate, doesn’t necessarily mean that there has been a reduction in performance, unless we say so in the report.

HM Inspector’s observations

I am satisfied with several aspects of the performance of Warwickshire Police in keeping people safe and reducing crime, but there are areas where the force needs to improve.

These are the findings I consider most important from our assessments of the force over the last year.

The force needs to improve how it identifies victims’ vulnerability at first point of contact

Warwickshire Police is missing opportunities to safeguard vulnerable people. It needs to improve how it assesses calls from the public, so that vulnerable people and repeat callers are routinely identified. And it needs to do better at consistently giving advice to people about preventing crime and preserving evidence when they contact the force.

The force needs to make sure that it carries out effective investigations, giving victims the support they need

Despite the force’s efforts to improve how it investigates crime, too many of its serious investigations aren’t supervised well enough and aren’t effective enough. This is resulting in a poor service to some victims of crime. The force doesn’t always pursue evidence-led prosecutions where appropriate. And it doesn’t always follow the Code of Practice for Victims of Crime or give enough support to victims by assessing their needs accurately.

The force needs to make sure that it has the right people in the right place with the right skills

Although the force has invested substantially in its information technology (IT) infrastructure, which it hopes will improve its efficiency and effectiveness, we found that staff are being moved from critical areas of work to manage demand, and that some teams were under-resourced and without the specialist skills needed to perform their role. The force needs to optimise the benefits of its IT programme and make sure there is sufficient capacity, capability and supervisory oversight in teams that manage offenders and outstanding suspects, especially those who pose the highest risk of harm to the public.

Warwickshire Police has recently reviewed its operating model. Its investments in managing vulnerability are aimed at helping the force respond to threat, harm and risk more effectively, enabling it to give a better service to the public.

It has been necessary for the force to revise its infrastructure at the same time as making changes to its systems. As stated above, this year the force has transformed its approach to IT, exemplified by the introduction of a new control room. Although at the time of our inspection it was too early to assess the benefits of these changes, the scale and pace of this transformation shouldn’t be underestimated. And the strategic plans the force has put, and is putting, in place give cause for optimism. But the plans must be carefully reviewed. We look forward to seeing the progress of the force’s plans.

My report sets out the more detailed findings of this inspection. I will continue to check the force’s progress in addressing these in the coming months.

Wendy Williams

HM Inspector of Constabulary

Providing a service to the victims of crime

Victim service assessment

This section describes our assessment of the service Warwickshire Police provides to victims, from the point of reporting a crime through to the end result. As part of this assessment, we reviewed 90 case files.

When the police close a case of a reported crime, it will be assigned what is referred to as an ‘outcome type’. This describes the reason for closing it.

We also reviewed 20 cases of when the following outcome types were used:

- A suspect was identified, and the victim supported police action, but evidential difficulties prevented further action (outcome 15).

- A suspect was identified, but there were evidential difficulties, and the victim didn’t support or withdrew their support for police action (outcome 16).

- A suspect was identified, but the time limit for prosecution had expired (outcome 17).

While this assessment is ungraded, it influences graded judgments in the other areas we have inspected.

The force needs to improve the time it takes to answer emergency and non‑emergency calls, and how it identifies repeat or vulnerable victims

When a victim contacts the police, it is important that their call is answered quickly and that the right information is recorded accurately on police systems. The caller should be spoken to in a professional manner. The information should be assessed, taking into consideration threat, harm, risk and vulnerability. And the victim should receive appropriate safeguarding advice.

The force isn’t meeting national standards for the time it takes to answer emergency calls, and needs to improve this. It also needs to improve the speed at which it answers non-emergency calls to prevent the caller abandoning the call. When calls are answered, the victim’s vulnerability is often not assessed using a structured process. Repeat victims aren’t always identified, which means this information may not be taken into account when considering the response victims should receive. Victims aren’t always given advice on how to prevent crime or preserve evidence.

The force doesn’t always respond to calls for service quickly enough

A force should aim to respond to calls for service within its published time frames, based on the prioritisation given to the call. It should change call priority only if the original prioritisation is deemed inappropriate, or if further information suggests a change is needed. The response should take into consideration risk and victim vulnerability, including information obtained after the call.

The force’s attendance was often outside its recognised timescales. Victims sometimes weren’t told about delays, and their expectations weren’t met. This may cause victims to lose confidence and disengage from the investigation.

The force allocates crimes to appropriate staff

Police forces should have a policy to make sure crimes are allocated to appropriately trained officers or staff for investigation or, if appropriate, not investigated further. The policy should be applied consistently. The victim of the crime should be kept informed of the allocation and whether the crime is to be further investigated.

The force’s arrangements for allocating recorded crimes for investigation were in accordance with its policy. In all the cases we reviewed, the crimes were allocated to the most appropriate department for further investigation.

The force isn’t always carrying out thorough investigations or conducting victim needs assessments

Police forces should investigate reported crimes quickly, proportionately and thoroughly. Victims should be kept updated about the investigation and the force should have effective governance arrangements to make sure investigation standards are high.

Effective supervision wasn’t always evident in the force’s crime investigations. This resulted in some investigations not being thorough enough. So victims are potentially being let down and offenders may not be being brought to justice. When domestic abuse victims withdrew their support for a prosecution, the force didn’t always consider the use of orders designed to protect victims, such as a domestic violence protection notice or a domestic violence protection order. Obtaining such orders is an important method of safeguarding the victim from further abuse in the future.

Under the Code of Practice for Victims of Crime, there is a requirement to conduct a victim needs assessment at an early stage, to decide whether victims need additional support. The outcome of the assessment and the request for additional support should be recorded. The force isn’t always completing the victim needs assessment. This means not all victims will get the appropriate level of service.

The force isn’t always using the appropriate outcome or obtaining an auditable record of victims’ wishes

The force should make sure it follows national guidance and rules for deciding the outcome of each report of crime. In deciding the outcome, the force should consider the nature of the crime, the offender and the victim. And the force should show the necessary leadership and culture to make sure the use of outcomes is appropriate.

When a suspect has been identified, but evidential difficulties prevent further action, the victim should be informed of the decision to close the investigation. Victims weren’t always told about decisions to take no further action and to close investigations.

When a suspect has been identified but the victim doesn’t support or withdraws their support for police action, the force should make sure it has an auditable record from the victim, confirming their decision. This will allow the investigation to be closed. Evidence of the victim’s decision was absent in most cases we reviewed. This means that victims’ wishes may not always be fully represented and considered before the investigation is closed.

When a crime can only be prosecuted in the magistrates’ court, prosecution must start within six months of the offence being committed. An investigation can be closed if a suspect has been identified but the time limit has expired. The force used this outcome incorrectly on several occasions.

Engaging with and treating the public with fairness and respect

Warwickshire Police is adequate at treating people fairly and with respect.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to treating people fairly and with respect.

The force involves its communities in local policing activity

The force has a ten-week Citizens’ Academy programme. The programme is open to the public and helps people to learn more about policing and how they might get involved. Some attendees may go on to become a cadet, volunteer or special constable. This helps the force and local people work together more effectively.

The force also has a popular police cadet programme, which currently has 120 members. The selection process examines the unique circumstances of each individual and what the programme can offer them. Unsuccessful applicants are invited to join local youth independent advisory groups.

There is a group of 74 police support volunteers who work in a range of roles, assigned based on their skills and experience. For example, Neighbourhood Watch Schemes keep the force updated about local policing issues that affect communities, while horseback volunteers support the force in preventing crime in rural areas.

The force works with all its communities to understand and act on what matters to them, but it needs to make sure this work can be accessed by everyone

The force uses a community messaging service called Warwickshire Connected, which complements established social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. The messaging service is an interactive way for people to tell the police about problems in their communities and to get information. At the time of our inspection, more than 4,700 people had subscribed to it.

We were told about several examples of face-to-face events where neighbourhood policing teams meet their communities, such as Sikh women’s groups, church meetings, and community events held for older people. The teams also visit schools and youth organisations. Local policing priorities are set through monthly problem-solving and vulnerability meetings. Using a polling system, the community can vote on local concerns and problems to help influence where the force sends its visible community patrols. But the extent to which this community interaction is planned and co-ordinated isn’t very clear.

It is important that the force continues to use all available contact channels to communicate with its communities, and that it doesn’t exclude those who don’t use or don’t have ready access to online methods. One example of this exclusion is an online-only survey. Not everyone in the community could access the survey, and therefore it wasn’t fully representative of local communities. The upcoming recruitment of dedicated police community support officers should support this by enabling more in-person contact. But these roles weren’t in place at the time of our inspection, so we haven’t been able to assess their effectiveness.

The force is trying to understand and improve the way it uses stop and search and use of force powers, but needs to do more

The force provides good governance through a chief officer-led legitimacy board. The board considers all forms of public interaction and the use of police powers. A use of police powers board focuses on data and trends, but the breadth and depth of the data it analyses could be increased.

There are gaps in what the force chooses to monitor. For example, it doesn’t analyse data about people who are stopped and searched more than once, or about the officers and teams that carry out the stop searches. Similarly, the force doesn’t monitor the level of injury caused to people by type of force used. It also doesn’t monitor the ethnicities of the members of public involved. For example, the force doesn’t know if Black people who are handcuffed are more or less likely to be injured or injured more severely than White people.

A new app, called a power app, has recently been introduced. It is intended to improve the quality of information available to the force, but at the time of this inspection it was too early to see results. Internal audits were also recently introduced, where supervisors should dip sample clips of BWV when it was in use when a person has been stopped and searched or when force has been used. But this process was found to be ineffective as supervisors weren’t always carrying out the audits and evidence of learning was limited, affecting the force’s ability to understand whether its use of coercive powers is fair. A new framework has been devised which should increase how often supervisors carry out audits.

During our inspection, we reviewed a sample of 170 stop and search records dated from 1 January to 31 December 2021. Based on this sample, we estimate that 88.2 percent (with a confidence interval of +/- 4.6 percent) of all stop and searches by the force during this period had reasonable grounds recorded. This is broadly unchanged compared with the findings from our previous review of records in 2019, where we found 86.0 percent (with a confidence interval of +/- 4.3 percent) of stop and searches had reasonable grounds recorded. Of the records we reviewed for stop and searches carried out on people from ethnic minority backgrounds, 29 of 34 had reasonable grounds recorded.

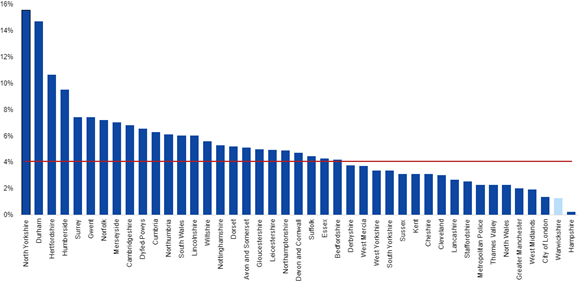

Although Warwickshire Police is trying to address disproportionality, this is still substantial. In the year ending 31 March 2021, people from ethnic minority backgrounds were four times as likely to be stopped and searched as people from White backgrounds. People of Black or Black British ethnicity were 13 times as likely to be stopped and searched as White people. People of Asian or Asian British ethnicity were three times as likely to be stopped and searched, and people of mixed ethnicity were four times as likely.

Figure 1: Relative rate for individuals from ethnic minority backgrounds to be stopped and searched compared to individuals from White backgrounds, for the year ending 31 March 2021

The force recognises it has work to do to tackle disproportionality, and has explored the reasons for this. Minutes and data are published on the website, as are disproportionality reports.

The use of police powers board is an effective meeting which is driving improvements to the force’s practices, policies and procedures. The force should continue to invest in this, paying particular attention to further explorations of the reasons for disproportionality. This will help to reassure the force and the public, and show that the force’s use of force and stop and search is fair.

Adequate

Preventing crime and anti-social behaviour

Warwickshire Police is adequate at prevention and deterrence.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to prevention and deterrence.

The force analyses its own data and data from partner agencies to establish high-demand and vulnerable locations, people and suspects, including repeat victims

The force regularly carries out data analysis, and appropriate information is discussed at monthly problem-solving meetings. The police data is shared with Warwickshire County Council’s community safety partnership analyst, who prepares reports for monthly problem-solving meetings. The meetings are attended by other agencies and workers including rough sleepers co-ordinators, the probation service, community safety wardens, district councils and the county council. Data from several agencies is used effectively to set priorities and co-ordinate work.

The force’s harm hub assesses information and intelligence to identify vulnerable people and repeat victims. This helps to identify children who need safeguarding. We saw evidence of risk management plans being used well to support repeat and vulnerable victims. One example involved an elderly person who was targeted by county lines drugs gangs. The local neighbourhood team followed a plan and used anti-social behaviour legislation effectively to protect the victim from further harm.

The force adopts early intervention approaches with a focus on positive outcomes

We found many cases of the force demonstrating creativity in its approach to early intervention. For example, it set up a boxing and fitness club to divert local teenagers away from criminality. The youth engagement team visits schools and colleges to hold educational inputs and workshops. The team shares safety messages about knife crime and county lines. It helps young people to understand the consequences of their decisions and gives them knowledge of the law.

Warwickshire Police takes an active role in county wide multi-agency vulnerability meetings. The force’s approach is to divert people away from criminal activity, and these meetings identify people who may benefit from early help and support from different agencies. This offers several potential benefits, including a probable reduction in long-term demand for the force. The other agencies said they valued these meetings.

The force works with other organisations and uses problem solving to help prevent crime, anti-social behaviour and vulnerability

A third of Warwickshire’s population live in rural communities. The force decided to introduce a rural crime team based on national good practice guidance. This has helped the force to be more effective when supporting neighbourhood teams, carrying out regional operations and sharing intelligence. A comprehensive performance framework means the force can evaluate its success against different types of crime, including:

- wildlife;

- agricultural vehicles and plants;

- livestock;

- equine;

- fly-tipping and waste;

- fuel; and

- heritage crime.

The rural crime team’s co-ordinator makes sure a problem-solving approach is taken when new crime trends emerge. The team attends community events such as livestock markets and agricultural shows, where it offers preventative advice. A recent example involves the theft of GPS agricultural systems. The force worked with the National Farmers Union to buy marking kits and trackers. These were distributed to farmers whose property was more vulnerable to theft. The farmers were also given practical crime reduction advice. This helped to reduce the number of GPS systems that were being stolen, and served to strengthen the force’s relationship with the farming community.

The force doesn’t have an effective system in place for recording, monitoring and sharing problem-solving plans, and the plans aren’t always updated, supervised or evaluated

Warwickshire Police understands the benefits of problem solving. But it doesn’t consistently record, monitor or evaluate how it tackles policing problems. When we examined its problem-solving plans, we found that they varied. Staff told us that a recent change in IT systems had made it difficult to record these plans. This means that senior leaders can’t evaluate performance accurately.

We found good examples of problem-solving plans being used beyond neighbourhood policing, which is encouraging. In one example, a problem-solving plan was used to manage a person who made repetitive malicious complaints about sexual offences.

But at the time of our inspection the force lacked an effective way to review and evaluate its problem-solving plans. It is in the process of recruiting a problem-solving advisor, as well as administrative support. This will allow the force to quality assure its problem-solving plans better, and give specialist advice about problem-solving to its staff.

Adequate

Responding to the public

Warwickshire Police requires improvement at responding to the public.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force responds to the public.

The force can’t effectively manage the number of non-emergency public calls for service, and needs to reduce the abandonment rate and caller wait times

The number of calls to the force switchboard and the 101 service (for non-emergency calls) that are abandoned by the caller is high and above the national required standard. Abandonment generally happens at the first point of contact or later, when the caller is transferred to the police. The force told us that 18.3 percent of the 101 calls it receives are abandoned. The national standard states that a force with a switchboard should have no more than 5 percent non-emergency abandonment.

The force has a performance framework which monitors abandonment rates for non‑emergency calls on a daily and weekly basis. But this framework hasn’t led to improvements. Delays in calls being answered will lead to more calls being abandoned, and potentially reduce public confidence in the force’s ability to respond.

The force has made improvements to support the wellbeing of its contact management staff, but more work is needed

In its force management statement, the force recognised that the operational control centre (OCC) building, telephone and IT systems were long overdue for replacement or upgrades. It also noted that demand, staffing and the working environment were affecting the wellbeing of the OCC staff.

The force introduced a new control room in March 2022. At the same time, substantial investment in IT saw replacements and updates to IT systems in the control room. While the relocation and IT upgrade caused additional pressure, this was unavoidable. Performance stayed relatively stable, and the force now has a modern control room that is fit for purpose.

The upgrade of the systems and office space has improved working conditions. There also are other bespoke wellbeing arrangements available to help make the staff feel valued.

But despite improvements to the working environment and systems, we found that staff in the OCC feel a strong focus on performance is affecting their wellbeing, and they don’t feel supported. At the time of our inspection, the force told us that the OCC had the highest rate of sickness in the force.

The force should continue to find ways to seek advice from experts to inform better decision making

Frontline officers feel well supported when dealing with incidents involving mental health concerns. The mental health street triage scheme has two cars staffed with a police officer and a mental health professional, operating daily between 2pm and 2am. They give advice and help to officers and call handlers. If needed, and when possible, they attend incidents and deal with the person directly. Call handlers told us that they can also refer open logs to the mental health team, who will assess and refer to other organisations, such as mental health organisations.

Nineteen officers have had five days of mental health training to equip them for this role. During our inspection, response officers spoke positively about mental health triage. They told us that it means they detain fewer people under section 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983 because other solutions are found. Mental health partners said that they have seen a reduction in the inappropriate use of section 136 as a result. This means a better outcome for the person suffering a mental health crisis, as they don’t have to be detained at a police custody suite.

But we were told that there aren’t always enough staff to operate the triage car, and mental health professionals aren’t always available. When a call is taken outside these hours, we were told that calls may not be resourced until the triage car is next on duty. This can lead to a delay in responding to mental health concerns. Officers told us that they would welcome more training in how to support people experiencing mental ill-health.

The force is good at assessing victims’ vulnerability and risk at domestic abuse incidents

In 2019, 257 officers and staff received domestic abuse matters training, and this year a further 233 officers and staff received training. There are 16 more training dates booked between January 2023 and March 2023, when it is hoped that approximately 200 more officers and staff will be trained. This training package has been developed with the College of Policing and SafeLives to support a cultural shift in the way police officers and staff approach domestic abuse incidents.

Officers we spoke to showed a clear understanding of their role and importance in safeguarding victims of domestic abuse. And we found that staff felt confident assessing risk at domestic abuse incidents using domestic abuse, stalking, harassment and honour-based violence risk assessments and vulnerable adult risk assessment accurately and where appropriate. Supervisory reviews of the risk assessments are effective and high-risk cases are referred effectively to the domestic abuse unit for further intervention and information sharing.

Requires improvement

Investigating crime

Warwickshire Police requires improvement at investigating crime.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force investigates crime.

The force has increased staff training to improve the quality of investigations and outcomes for victims

The force has introduced a five-day immersive course for patrol officers, called Operation Sherlock. The course aims to improve the quality of investigations and outcomes for the victim. The training covers crime scene management, ways to secure evidence at the earliest opportunity, court disclosure of evidence requirements and court processes.

The force told us that so far 170 student officers have completed the training programme. There are a further seven courses planned for this year. The force also intends to give this training to frontline supervisors. Staff we spoke to who have received the training told us they felt more confident and knowledgeable about the action they need to take to make sure investigations are completed effectively.

The force currently has insufficient capacity and capability to carry out investigations

Warwickshire Police’s staff are young and inexperienced. This includes its tutors and supervising officers. The force offers several ways for people to join its workforce, including a degree-holder entry programme. But managing these different routes is difficult, because they add to the demands faced by tutors, who often carry high workloads. This means tutors can’t always support students effectively, which affects how well the force investigates crime.

We found that the force had recently finalised 963 investigations. This took place over a three- to four-week period, and was called Operation Zakynthos. We were assured that it was planned thoroughly, and the force understood the consequences of finalising these investigations. There is a force investigations, standards and outcome board, which oversaw the operation and a subsequent evaluation. This has led to additional training being given to staff. But at the time of our inspection, it wasn’t clear how this has led to sustainable improvements. We found examples of cases being finalised when investigative opportunities were present. This showed that quality assurance processes hadn’t always been effective.

But the force is changing its operating model to help it cope with demand more effectively. It is creating specialist teams that will investigate serious sexual offences, including rape. At the time of our inspection these changes hadn’t happened, so we weren’t able to assess if they are effective.

The force understands the steps it must take to make sure that it can investigate crime effectively and achieve better outcomes for victims

We were satisfied that senior leaders understood the underlying problems the force faces in investigating crime effectively. The force’s governance structure helps it to identify problems and act quickly to solve them. But these are new arrangements, and their benefits weren’t yet apparent at the time of our inspection.

But the force has responded well to our previous recommendation about its processes for allocating investigations to different teams. We found that almost all reports of crime are allocated in line with the force’s policy, and a clear escalation process is in place.

Investigators maintain regular contact with victims throughout investigations

We found that investigators adhered to victim contact expectations and timings in most cases. The force’s victims’ experience board scrutinises compliance with the Victims’ Code. Each week, a report is published to help supervisors understand how well their teams are performing. The force complements this with an online performance dashboard, which is available to all staff. This digital tool helps the force to understand investigative demand and how well staff are supporting victims.

During our reality testing, we confirmed that officers and supervisors appreciate why regular contact with victims is important.

The force identifies opportunities to improve its forensic capabilities

In September 2021, the force entered a formal collaboration with West Midlands Police for forensic services. This will be reviewed after 12 months to establish if it is achieving the benefits both forces predict. Notably, a backlog of forensic submissions has reduced, and early indications are that examination times have improved. The force can speed up urgent cases, and staff we spoke to were positive about the introduction of digital kiosks. These kiosks help trained staff to examine digital devices quickly for evidence.

The force’s arrangement with West Midlands Police also gives it access to wider specialist forensic support. We look forward to learning more about the benefits of this collaboration in future.

Requires improvement

Protecting vulnerable people

Warwickshire Police is adequate at protecting vulnerable people.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force protects vulnerable people.

The force works effectively and proactively with partner agencies and other organisations to reduce vulnerability

The force has collaborated with Warwick University to produce films about alcohol awareness, exploitation and violence against women and girls. The films are shown using virtual reality headsets and are aimed at 15- to 20-year-old boys and men, those in further education, and first-year university students. It will also be shown to police officers who may be dealing with incidents of violence against women and girls.

A film about violence against women and girls (Five Women, One Story) will be used to raise awareness about the effects of actions that could be seen as ‘minor’ or normal. It encourages boys and young men to challenge inappropriate behaviour by their peers. The film discusses online abuse and unwanted touching. The force consulted with subject matter experts, including charities, partner agencies and those with direct experience, to help develop the film. It will be shown at schools in late 2022, and the force is considering ways to incorporate the film into its police officer training programmes.

There are effective multi-agency safeguarding arrangements in place

Warwickshire Police has well-established multi-agency risk assessment conference (MARAC) arrangements in place and these follow SafeLives guidance. The force told us that this is corroborated by a recent SafeLives review. Multi-agency relationships at both strategic and practitioner level work well. Multi-agency processes help the force and those it works with to manage those who cause the most harm and to keep victims safe.

There are three conferences across the county, with one chairperson and co‑ordinator, which supports a consistent approach to safeguarding. The conferences take place on a regular basis.

The MARAC is well attended by a range of partner agencies and third-sector organisations including housing, adult and children services, public health services, and independent domestic violence advisers. Where an agency is unable to attend, meaningful updates are given in advance of the conference. Participants actively contribute when discussing high-risk cases. They focus on safety planning and risk management for victims, perpetrators and children exposed to domestic abuse. Actions to protect victims are reviewed and referrals involve a good blend of agencies. We saw several cases discussed where protective orders were in place or considered. This approach helps provide effective protection to vulnerable victims.

The force should make sure that orders such as domestic violence protection notices and orders are considered in all appropriate cases

As part of our victim service assessment, we found that domestic violence protection orders (DVPOs) and other ancillary orders were considered in just 5 of 15 applicable cases we reviewed. This may mean that opportunities to prevent further harm to victims of domestic abuse are being missed.

All high-risk domestic abuse cases are currently managed by either the criminal investigation department or the domestic abuse unit. The domestic abuse unit is effective at co-ordinating applications for DVPOs and scrutinising applications for stalking and prevention orders. But all standard and medium-risk domestic abuse cases are managed by response officers, and it is unclear whether DVPOs are always considered.

Response officers told us that they would welcome more guidance and training on ancillary orders and the Domestic Violence Disclosure Scheme (Clare’s Law).

Adequate

Managing offenders and suspects

Warwickshire Police requires improvement at managing offenders and suspects.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force manages offenders and suspects.

The force effectively pursues outstanding suspects and wanted persons to protect the public from harm, but its management of outstanding suspects is inhibited by poor quality data

We found that the force prioritises arresting outstanding suspects using its daily management meeting, where leaders scrutinise progress in making arrests.

High-risk offenders are handed over between shifts in patrol and criminal investigation department teams, and frontline response officers can check with the control room whether someone is wanted. There is a positive culture of pursuing suspects effectively, and we found teams supported each other well when it came to apprehending outstanding suspects. Our victim service assessment confirmed that the force arrests suspects promptly.

The force can track the number of outstanding suspects, but the process relies on staff making sure they update a suspect’s status on the force’s systems accurately. This makes it difficult for the force to monitor and prioritise progress. Unless processes are followed consistently, the force’s data will be inaccurate. During our inspection, the force couldn’t give an accurate picture of the number of outstanding suspects.

Outstanding offenders and wanted or missing persons are circulated on the police national computer after they are reviewed and risk assessed by a supervisor. But we found that this information wasn’t circulated in a consistent way. This is made more difficult by the force currently transferring data about outstanding suspects between different records management systems. At the time of our inspection, the force told us that 30 data packages still had to be transferred.

But when the transfer process is complete, the force will have access to data about outstanding suspects each day. This will support more effective performance management processes, including being able to review cases by their overall duration and the severity of the offences involved.

The force works well with other organisations, but needs to make sure that the integrated offender management team can manage its workload in a sustainable way

The force has a well-established integrated offender management (IOM) programme, and works together with other organisations. At the time of our inspection, the IOM team had been reduced to less than half its original size and had no analytical support. This means that staff were managing a high workload. Additional members of staff have been allocated to the team, but the force needs to make sure that the team can operate sustainably.

The IOM staff we spoke to were highly committed, but the team doesn’t have the capacity to manage demand. It often relies on other teams for support, for example, when visiting offenders. This affects how proactive staff are, and demands in other teams mean they sometimes visit offenders without sufficient support.

IOM meetings are well attended by the police and other agencies. These include the probation service, housing services and the prison service resettlement officer. These meetings review offenders who are due for release, new referrals, and offenders who are already managed under the IOM scheme. There are good levels of information sharing and agencies combine their efforts to achieve good outcomes. The IOM team shares premises with probation, which helps to build strong and effective relationships.

The force has identified that it can improve how it manages high-risk offenders. A proposal has been made under the new operating model to create a high-risk offender management unit. This will make sure the most violent or dangerous offenders are subjected to more effective management.

The force doesn’t refer offenders to intervention and perpetrator programmes to reduce re-offending, and needs to better understand the benefits and outcomes of managing offenders effectively

We found good examples of multi-agency working to reduce re-offending throughout the force. But we didn’t find evidence of the force using or being able to use any schemes to help reduce the likelihood of further offending, for example, diversionary intervention schemes or programmes for perpetrators of domestic abuse.

The force doesn’t routinely evaluate the cost and benefit of managing offenders through the IOM scheme. As a result, it can’t fully assess the effectiveness of its approach to reducing re-offending. It doesn’t know whether its investment in offender management is sufficient, beneficial, or targeted at the right group of offenders. The force has returned to using IDIOM, a web-based offender tracking tool which is provided by the Home Office to police forces to support IOM. Once this tool has been used for a reasonable length of time, the force will have data to show how it is affecting re-offending rates.

The force has effective digital capability, but capacity is limited

The force has invested in digital media investigators (DMIs) whose role is to give on‑scene expert digital advice and support to officers, including the OCSET team. DMIs can review devices belonging to suspects for evidence of criminal activity. This helps the investigations by gathering evidence quickly and accurately.

DMIs support investigations by participating in briefings, attending incidents, and preserving evidence and data that can be used by OCSET investigators. But there are only three trained DMI officers, and they aren’t available for every case. A recent proposal for more staff has been provisionally agreed by the force, but their recruitment and training will take time.

Requires improvement

Disrupting serious organised crime

Warwickshire Police requires improvement at disrupting serious organised crime.

Read the report for Warwickshire police: An inspection of the West Midlands regional response to serious and organised crime – May 2024

Background

We now inspect serious and organised crime (SOC) on a regional basis, rather than inspecting each force individually in this area. This is so we can be more effective and efficient in how we inspect the whole SOC system, as set out in HM Government’s SOC strategy.

SOC is tackled by each force working with regional organised crime units (ROCUs). These units lead the regional response to SOC by providing access to specialist resources and assets to disrupt organised crime groups that pose the highest harm.

Through our new inspections we seek to understand how well forces and ROCUs work in partnership. As a result, we now inspect ROCUs and their forces together and report on regional performance. Forces and ROCUs are now graded and reported on in regional SOC reports.

Requires improvement

Building, supporting and protecting the workforce

Warwickshire Police is adequate at building and developing its workforce.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force builds and develops its workforce.

The force has an inclusive culture that promotes a sense of belonging, with staff proud to work for Warwickshire Police

Throughout our inspection we were told and could see that the force has a ‘family like’ culture. Its culture is based on respect, and staff feel comfortable to challenge colleagues and supervisors if needed. ‘We are Warwickshire’ is a positive brand that promotes the force’s identity and supports workforce inclusivity.

The force holds annual events, and includes family members so that they can see what the force does. We found a workforce that is proud to work for Warwickshire and is hopeful for the future. This was consistent throughout our inspection, and was supported by a survey that staff completed for us. The force was described by one member of staff as “small but beautiful”.

The force has a maximising innovation group, which works on innovative ideas force‑wide. For example, it is introducing a ‘mojo award’, which is intended to bridge the gap between rewards and recognition. The award will focus on effort, behaviour and the mindset of the individual. It will be introduced in summer 2022. This is a significant development, but we can’t assess its effectiveness because it is so new.

While the force has recently surveyed its staff about inclusivity, integrity, behaviours and harassment, the results weren’t available during our inspection. Data has been collected to allow future analysis of protected characteristics in this context.

The senior leadership team promotes an ethical performance and behaviour culture

There is a strong governance framework in place for ethics and culture, with a clear commitment from chief officers. Staff told us that senior leaders are always approachable, lead by example, and are accountable.

The force has recently introduced an ethics culture, conduct and behaviours board to address the following themes:

- officers’ off-duty conduct and use of social media;

- performance requiring improvement;

- violence against women and girls;

- abuse of position for sexual purposes; and

- inappropriate professional behaviours.

Discussions and expectations from the meetings are reinforced through chief officer vlogs and leadership development programmes.

The force has an internal ethics committee which has been reinvigorated following the pandemic. The committee meets quarterly. While at the time of our inspection a permanent chair was being sought, there are several independent members. Ethical dilemmas are submitted via the force’s intranet site on a form that is available to all staff. The head of professional standards reviews submissions to confirm that they amount to an ethical dilemma. Issues raised that can or should be dealt with by management action are signposted appropriately.

The committee is promoted through the circulation of a professional standards newsletter each quarter, on the intranet and at staff training events, including supervisors’ development days. Our inspection found a very mature understanding of ethics among the workforce. But despite the force’s work to promote the committee, the staff that we spoke to generally didn’t have wider knowledge of the committee’s existence or awareness of how to submit ethical dilemmas.

The force listens to feedback from the workforce, so its staff feel confident to voice concerns

The force has used findings from its surveys to improve regional practice. The results of these surveys highlighted that it was difficult for officers to manage the demand presented by their student officer rotations and assessments.

The force submitted a proposal to the College of Policing suggesting the curriculum be changed, so that forces are better able to balance the need to meet academic requirements and the College of Policing’s requirements. The proposal included the suggestion that modules should be combined. Doing this would make the process smoother for officers who are being assessed. The proposal was accepted and Warwickshire will be the first force to implement this change. Protected learning time is built in for student officers. The force has provided an extra three protected learning days to help them. All four forces in the region will eventually adopt the same approach that Warwickshire is leading on.

The force decided not to continue with the national wellbeing survey, which is being carried out by Oscar Kilo and Durham University to give staff the opportunity to say how they truly feel at work. The force will instead be running their own survey. This will be circulated this year to gain a deeper understanding of how staff are feeling two years after the end of the alliance arrangement with West Mercia Police.

The force has worked hard to understand attraction and attrition in recruitment, and is prioritising positive action to increase the diversity of the workforce

The force has a positive action officer who listens to candidate feedback and works with other corporate teams such as communications and HR to help create more attractive and effective recruitment campaigns.

The positive action officer devises newsletters and makes direct contact with candidates to coach and mentor them, and keep them engaged in the application process. The work on positive action is supported by the force’s staff networks. They contact individuals to give support, for example, by holding mock practice assessment centres and workshops. For existing staff, the force offers support through the internal promotion process. Individuals from under-represented groups are notified of opportunities for career development, and volunteers that the force calls ‘positive action champions’ support potential applicants.

The force works with its communities to increase representation within the workforce. Community members are now involved in the process as volunteer recruitment interviewers, and there are 23 positive action champions within the community.

At 31 March 2021, 6.7 percent of Warwickshire Police’s workforce (who had stated their ethnicity) were from ethnic minority backgrounds, compared with 7.3 percent of the local population. In the year ending 31 March 2021, the proportion of joiners who were from ethnic minority backgrounds was higher, at 8.2 percent.

Figure 3: Proportion of Warwickshire Police workforce and workforce joiners that self‑identify as being from ethnic minority backgrounds at 31 March 2021, compared to the local population

Note: these calculations exclude ethnicities that weren’t stated, which represented 3.2 percent of the workforce and 8.7 percent of joiners

As there is currently only one positive action officer, they are limited in what they can achieve, but the force intends to increase the capacity of this team.

The force has a workforce representation plan based on the National Police Chiefs’ Council’s diversity, equality and inclusion guidance. The plan focuses on leadership and culture, attraction and recruitment, retention, wellbeing, and fulfilment. The force also has a diversity and inclusion strategy, which focuses on five main themes:

- Growing a workforce which is representative of the communities they serve.

- Being an employer of choice that attracts, recognises and retains the very best

- Developing an inclusive culture within the force at all levels and ranks.

- Supporting members of the workforce to reach their potential.

- Putting the health and wellbeing of the workforce first.

Attrition rates for members of the workforce from ethnic minority backgrounds are monitored monthly, and detailed scrutiny of exit data is carried out and shared. The action taken by the force is starting to have positive results.

Vetting and counter corruption

We now inspect how forces deal with vetting and counter corruption differently. This is so we can be more effective and efficient in how we inspect this high-risk area of police business.

Corruption in forces is tackled by specialist units, designed to proactively target corruption threats. Police corruption is corrosive and poses a significant risk to public trust and confidence. There is a national expectation of standards and how they should use specialist resources and assets to target and arrest those that pose the highest threat.

Through our new inspections, we seek to understand how well forces apply these standards. As a result, we now inspect forces and report on national risks and performance in this area. We now grade and report on forces’ performance separately.

Warwickshire Police’s vetting and counter corruption inspection hasn’t yet been completed. We will update our website with our findings and the separate report once the inspection is complete.

Adequate

Strategic planning, organisational management and value for money

Warwickshire Police is adequate at operating efficiently.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force operates efficiently.

The force has an effective strategic planning and performance framework, making sure it tackles what is important locally and nationally

The force has made considerable investments as part of its plans to improve services and meet public expectations. In our 2019 PEEL report, we raised concerns about the force’s sustainability following the end of its strategic alliance with West Mercia Police. The force has put firm foundations in place to help it to stay sustainable.

Warwickshire Police’s leaders and staff show a deep commitment to improving the force’s services to the public. The force’s strategic plans are aligned to the Police and Crime Commissioner’s Plan for 2021–25 and are described in its force management statement. We saw how the force’s objectives are reflected in its plans. Its performance framework supports these priorities and will be improved by the force’s growing ability to use data. This means the force is in a stronger position to make informed decisions that support its plans.

The force is developing an operating model that should allow it to prioritise and meet future demands

As the force withdrew from its strategic alliance with West Mercia Police, it revised its operating model to make sure it could continue to provide its core services. But the force knew this model would need to be changed, and this was reinforced by the onset of the pandemic.

Warwickshire Police’s interim model gave it a base from which to develop its plans. The new operating model will inevitably mean more changes. So, the force is determining where pressures exist and reviewing processes to make sure this new model is fit for the future.

The force makes the best use of the finance it has available, and its plans are both ambitious and sustainable

The force’s medium-term financial plan (MTFP) is balanced and uses sensible assumptions. The force sought advice when it developed the MTFP. Throughout the year, the chief constable and other senior leaders participated in budget-setting discussions. These discussions focused on topics including:

- the force’s operating principles;

- planning assumptions;

- national and local operational factors;

- the capital programme;

- its use of reserves; and

- financial risks.

This means the force has identified the savings it needs to make, and it has plans in place to achieve what is needed. Sound financial management is apparent. The force’s planning process is effective, and the public can be confident that the force has a good approach to managing the service.

As part of the force’s transition from its strategic alliance arrangements, it worked with the Chartered Institute of Public Finance Accountancy under the Achieving Financial Excellence in Policing Programme. The force is expected to achieve a balanced budget for 2022/23. It isn’t reliant on the routine use of reserves to finance any budget shortfalls.

The force collaborates effectively and ambitiously with other organisations, achieving value for money

The force’s senior leaders understand the benefits of effective collaborations. The police and crime plan sets out how the force will continue to support work with other organisations by participating in the blue light emergency collaboration joint‑working group. The group comprises the police, fire and rescue service, ambulance service, and mental health agencies.

There are formal collaborative agreements in place for forensics, firearms training, regional organised crime and counter terrorism. We also found that the force seeks wider opportunities to collaborate and become more efficient.

Adequate

About the data

Data in this report is from a range of sources, including:

- Home Office;

- Office for National Statistics(ONS);

- our inspection fieldwork; and

- data we collected directly from all 43 police forces in England and Wales.

When we collected data directly from police forces, we took reasonable steps to agree the design of the data collection with forces and with other interested parties such as the Home Office. We gave forces several opportunities to quality assure and validate the data they gave us, to make sure it was accurate. We shared the submitted data with forces, so they could review their own and other forces’ data. This allowed them to analyse where data was notably different from other forces or internally inconsistent.

We set out the source of this report’s data below.

Methodology

Data in the report

British Transport Police was outside the scope of inspection. Any aggregated totals for England and Wales exclude British Transport Police data, so will differ from those published by the Home Office.

When other forces were unable to supply data, we mention this under the relevant sections below.

Outlier Lines

The dotted lines on the bar charts show one Standard Deviation (sd) above and below the unweighted mean across all forces. Where the distribution of the scores appears normally distributed, the sd is calculated in the normal way. If the forces are not normally distributed, the scores are transformed by taking logs and a Shapiro Wilks test performed to see if this creates a more normal distribution. If it does, the logged values are used to estimate the sd. If not, the sd is calculated using the normal values. Forces with scores more than 1sdunits from the mean (i.e. with Z-scores greater than 1, or less than -1) are considered as showing performance well above, or well below, average. These forces will be outside the dotted lines on the bar chart. Typically, 32% of forces will be above or below these lines for any given measure.

Population

For all uses of population as a denominator in our calculations, unless otherwise noted, we use ONS mid-2020 population estimates.

Survey of police workforce

We surveyed the police workforce across England and Wales, to understand their views on workloads, redeployment and how suitable their assigned tasks were. This survey was a non-statistical, voluntary sample so the results may not be representative of the workforce population. The number of responses per force varied. So we treated results with caution and didn’t use them to assess individual force performance. Instead, we identified themes that we could explore further during fieldwork.

Victim Service Assessment

Our victim service assessments (VSAs) will track a victim’s journey from reporting a crime to the police, through to outcome stage. All forces will be subjected to a VSA within our PEEL inspection programme. Some forces will be selected to additionally be tested on crime recording, in a way that ensures every force is assessed on its crime recording practices at least every three years.

Details of the technical methodology for the Victim Service Assessment.

Data sources

Incidents

We collected this data directly from all 43 police forces in England and Wales. This data is as provided by forces in December 2020.

Incidents as involving mental health concerns

We requested this data directly from all 43 police forces in England and Wales. This data is as provided by forces in December 2020.

Stop and Search

We took this data from the November 2021 release of the Home Office Police powers and procedures statistics. The Home Office may have updated these figures since we obtained them for this report.

Workforce figures (including ethnicity)

This data was obtained from the Home Office annual data return 502. The data is available from the Home Office’s published police workforce England and Wales statistics or the police workforce open data tables. The Home Office may have updated these figures since we obtained them for this report.

The data gives the full-time equivalent workforce figures as at 31 March 2020. The figures include section 38-designated investigation, detention or escort officers, but not section 39-designated detention or escort staff. They include officers on career breaks and other types of long-term absence but exclude those seconded to other forces.