Overall summary

Our judgments

Our inspection assessed how good Kent Police is in 12 areas of policing. We make graded judgments in 11 of these 12 as follows:

We also inspected how effective a service Kent Police gives to victims of crime. We don’t make a graded judgment in this overall area.

We set out our detailed findings about things the force is doing well and where it should improve in the rest of this report.

Important changes to PEEL

In 2014, we introduced our police effectiveness, efficiency and legitimacy (PEEL) inspections, which assess the performance of all 43 police forces in England and Wales. Since then, we have been continuously adapting our approach and this year has seen the most significant changes yet.

We are moving to a more intelligence-led, continual assessment approach, rather than the annual PEEL inspections we used in previous years. For instance, we have integrated our rolling crime data integrity inspections into these PEEL assessments. Our PEEL victim service assessment will now include a crime data integrity element in at least every other assessment. We have also changed our approach to graded judgments. We now assess forces against the characteristics of good performance, set out in the PEEL Assessment Framework 2021/22, and we more clearly link our judgments to causes of concern and areas for improvement. We have also expanded our previous four-tier system of judgments to five tiers. As a result, we can state more precisely where we consider improvement is needed and highlight more effectively the best ways of doing things.

However, these changes mean that it isn’t possible to make direct comparisons between the grades awarded this year with those from previous PEEL inspections. A reduction in grade, particularly from good to adequate, does not necessarily mean that there has been a reduction in performance, unless we say so in the report.

HM Inspector’s observations

I recognise that Kent Police, in common with other forces, has experienced many difficulties over the past year due to the pandemic. It has faced some unique difficulties in relation to Brexit and channel crossings because of the county’s geographical location.

I am satisfied with some aspects of its performance in keeping people safe and reducing crime, but there are areas where it needs to improve.

I consider the findings below most significant from our assessment of the force over the last year.

The force’s service to victims of crime and the way it responds to calls from the public requires improvement

Kent Police is missing opportunities to protect vulnerable and repeat victims of crime. It needs to improve the way it manages initial calls, so that all vulnerable people are identified. The force is often failing to complete assessments of victims’ needs or properly record the reasons why a victim doesn’t support an investigation. Staff taking calls often fail to provide advice on crime prevention or preserving evidence before the arrival of police officers. Officers’ attendance is also sometimes delayed.

The force needs to improve the way it investigates crime

The force must ensure that crimes are allocated promptly to officers who have both the capacity and capability to investigate them properly. Opportunities to achieve positive results for victims are being missed because investigations are poor, or because officers haven’t collected evidence, or persevered in all cases where the victim no longer wishes to pursue a prosecution. This lets victims down.

Kent Police’s response to domestic abuse is of particular concern

The force is rightly proud of some of its work protecting vulnerable people. However, domestic abuse investigation teams aren’t properly resourced with qualified staff. Some victims have received an unacceptable level of service and have continued to remain at risk. Investigations are often delayed or are of a poor quality. This has caused victims to disengage with the force and abusers to escape justice. Alternatives to prosecution, such as prevention orders, aren’t sufficiently used.

The force is outstanding at recording crime

The force has very effective crime recording processes. It is estimated that Kent Police is recording 96.7 percent of all reported crime.

The force is good at treating people fairly and with respect

Kent Police works well with communities. It has a good understanding of the effect that both the use of force and stop and search powers have on different communities. Officers have a good knowledge of what constitutes reasonable grounds for using these powers and the force has put in place an effective system of external scrutiny of their use.

The force is good at preventing crime and anti-social behaviour

Kent Police works proactively with other allied organisations to identify vulnerable victims and to take action to reduce risk and harm, using a range of prevention and enforcement measures.

The force promotes an ethical and inclusive culture and generally supports its workforce

The Code of Ethics is at the heart of policing in Kent with clear expectations that officers and staff will always act with integrity. The force has a good awareness of the needs and aspirations of its workforce. It provides excellent wellbeing support and a supportive culture of learning. However, it needs to improve the support given to some teams dealing with vulnerable victims.

The force is good at achieving savings and improving productivity

The force maximises both collaborative and digital opportunities to reduce costs and improve performance.

My report now sets out the fuller findings of this inspection. I will monitor the force’s progress as it addresses the areas where it can improve while acknowledging the good work it has already undertaken in other areas.

Roy Wilsher

HM Inspector of Constabulary

Providing a service to the victims of crime

Victim service assessment

This section describes our assessment of the service victims receive from Kent Police, from the point of reporting a crime through to the result. As part of this assessment, we reviewed 130 case files as well as 20 cautions, community resolutions and cases where a suspect was identified but the victim didn’t support or they withdrew support for police action. While this assessment is ungraded, it influences graded judgments in the other areas we have inspected.

The force answers calls quickly but should improve its identification of repeat or vulnerable victims at this first point of contact

When a victim contacts the police, it is important that their call is answered quickly and that the correct information is recorded accurately on police systems. The caller should be spoken to in a professional manner. The information should be assessed, taking into consideration threat, harm, risk and vulnerability. And the victim should get appropriate safeguarding advice.

At Kent Police, emergency calls and non-emergency calls are answered promptly and the force is meeting national and force standards. However, the vulnerability of victims isn’t always assessed using the force’s structured process. Repeat victims aren’t always identified, which affects decisions about the appropriate response. Not all victims are given advice about crime prevention or the preservation of evidence. This potentially undermines any investigation and the opportunity to prevent further crimes against the victim.

The force doesn’t always respond to calls for service in a timely way

A force should aim to respond to calls for service based on the prioritisation given to the call. It should change call priority only if the original prioritisation is deemed inappropriate, or if further information suggests a change is needed. The response should take into consideration risk and victim vulnerability, including information obtained after the call.

In most of the cases reviewed, the force responded appropriately, but sometimes attendance was slow and victims weren’t given updates about delays. When a victim’s expectations aren’t met, they can lose confidence and disengage. For non-emergency calls, the force’s appointment system was used effectively and, on most occasions, an appropriate staff member was allocated to respond.

The force is outstanding at recording reported crime due to good governance and leadership

The force’s crime recording should be trustworthy. It should be effective at recording reported crime in line with national standards and have effective systems and processes, supported by the necessary leadership and culture.

The force has outstanding crime recording processes, which make sure that crimes reported to the force are recorded correctly.

We set out more detail about the force’s crime recording in the ‘crime data integrity’ section below.

The allocation of crimes to officers is sometimes delayed and victims aren’t always promptly informed when a crime will not be investigated further

Police forces should have a policy to make sure crimes are allocated to appropriately trained officers or staff for investigation or, if appropriate, not investigated further. The policy should be applied consistently. The victim of crime should be kept informed of the allocation and whether the crime is to be further investigated.

Crimes reported to Kent Police were allocated to the most appropriate department for further investigation. However, sometimes there were subsequent delays in their allocation to an officer that could result in lost evidence and victims disengaging. Victims weren’t always informed promptly when it was decided that their report wouldn’t be investigated further. This could reduce their confidence in the police.

The force isn’t always carrying out thorough and timely investigations, with victims not always being updated on progress

Police forces should investigate reported crimes quickly, proportionately and thoroughly. Victims should be kept updated about the investigation and the force should have effective governance arrangements to make sure investigation standards are high.

In the cases we reviewed, a lack of effective supervision meant investigations were sometimes not carried out in a timely manner and sometimes relevant lines of inquiry weren’t completed. This lets victims down and prevents offenders being brought to justice. Many officers were conscientious about keeping victims updated, which maintains confidence in investigations, and some went over and above their duty, but occasionally victims didn’t receive the updates they should.

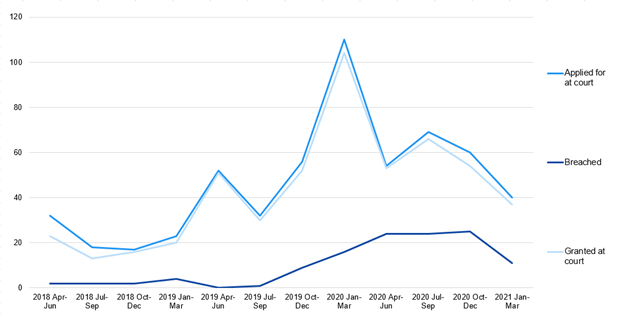

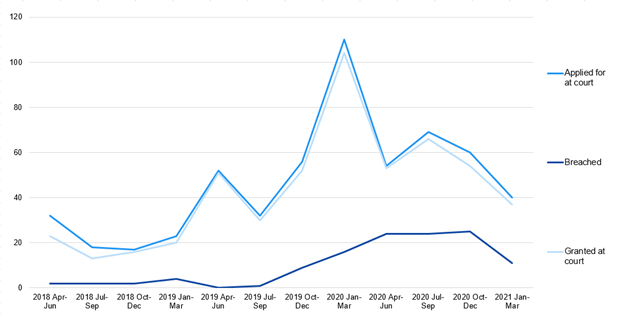

When domestic abuse victims withdrew their support for a prosecution, the force didn’t always consider the use of orders designed to protect them from further abuse, such as a Domestic Violence Protection Order (DVPO). The chart below shows the number of DVPOs applied for, granted and breached in Kent between 1 April 2018 and 31 March 2021. The data for the chart was extracted on 9 December 2021.

DVPOs applied for, granted and breached in Kent between 1 April 2018 and 31 March 2021

The Code of Practice for Victims of Crime requires the force to assess whether the victim needs additional support at an early stage and to record the outcome. The force isn’t always completing this assessment, which means that not all victims will get the appropriate level of service.

Results of investigations

The force closes reports of crimes appropriately but sometimes it fails to record the views of victims in reaching those decisions.

The force should make sure it follows national guidance and rules for deciding the results of each report of crime. In deciding this, the force should consider the nature of the crime, the offender and the victim. And the force should show the necessary leadership and culture to make sure the use of the results is appropriate.

When appropriate, offenders can be dealt with by means of a caution or community resolution, with the views of the victim taken into consideration. In most of the cases reviewed, the offender met the national criteria for the use of these procedures and the victim’s views were sought and considered. Where the victim doesn’t support or they withdraw support for police action, the force should have an auditable record of the decision, but this was absent in most cases.

Crime data integrity

Kent Police is outstanding at recording crime.

We estimate that Kent Police is recording 96.7 percent (with a confidence interval of +/- 1.9 percent) of all reported crime (excluding fraud). We estimate this means the force didn’t record over 5,600 crimes for the year covered by our inspection. Its performance is good for offences of violence against the person. We estimate that 94.1 percent (with a confidence interval of +/- 3.9 percent) of violent offences are being recorded. Its performance is good for sexual offences. We found an estimated 96.0 percent (with a confidence interval of +/-3.6 percent) of sexual offences were recorded.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well Kent Police provides a service to the victims of crime.

The force is good at recording domestic abuse

The force has been focusing particularly on the accurate recording of domestic abuse by checking that the correct crimes have been recorded from each incident. This is important to identify and safeguard potentially vulnerable victims from further abuse and to ensure that they are referred to support services.

The force is good at recording crimes within 24 hours of the report being made

Crimes should be recorded as soon as possible after being reported to minimise delays to the start of investigations. This reduces the risk of evidence being lost or victims disengaging. Kent Police has made significant improvements, particularly for rape, and is now recording the majority of crimes within 24 hours of a report being made.

The force has strong governance and leadership for crime recording

Senior officers review crime recording compliance and take action to improve poor performance. Chief officers regularly emphasise to staff the importance of recording crimes correctly, creating a culture that recognises its contribution to supporting victims and providing the service they deserve.

The force needs to review its approach to reports of rape to ensure that they are appropriately investigated

A report of a crime can only be cancelled in certain situations, such as when there is evidence that the crime didn’t occur or if it has already been recorded. In our case review, some rape allegations had been cancelled despite there being insufficient evidence to show they were false.

Recording data about crime

Kent Police is outstanding at recording crime.

Accurate crime recording is vital to providing a good service to the victims of crime. We inspected crime recording in Leicestershire as part of our victim service assessments (VSAs). These track a victim’s journey from reporting a crime to the police, through to the outcome.

All forces are subject to a VSA within our PEEL inspection programme. In every other inspection forces will be assessed on their crime recording and given a separate grade.

You can see what we found in the ‘Providing a service to victims of crime’ section of this report.

Outstanding

Engaging with and treating the public with fairness and respect

Kent Police is good at treating people fairly and with respect.

Main findings

In this section, we set out our main findings that relate to treating people fairly and with respect.

The force works with all its diverse communities to understand what matters to them and respond

The force works with its communities face-to-face and through social media. It effectively manages the way it does this with local communities by holding meetings with the residents of several wards at one time. Regular ward surgeries are carefully located where the force feels access to the community will be maximised. Dedicated community liaison officers in each district build relationships with people from diverse and vulnerable communities to better support them and to prevent and detect crime.

The force has developed strong links with its communities through the use of digital resources. It told us it has 380,000 followers across social media. It provides safety and reassurance messages, most recently with an emphasis on the effect of the pandemic, domestic abuse and anti-social behaviour. It uses Instagram to highlight crime stories and offer crime prevention advice and will respond to posts from the public. The chief constable has a weekly slot on local radio, providing updates and reassurance, showcasing force achievements and encouraging recruitment. Recently, 14,000 people attended the force’s three-day open day.

The workforce understands why and how it should treat the public with fairness and respect

Police officers and staff treat the public fairly and with respect. They have a sound understanding of what constitutes unfair behaviour towards the public and how to challenge poor behaviour. The Kent Police effective communication programme provides new recruits with knowledge, skills and understanding of human interaction including non-verbal communication and how attitude affects behaviour. Annual personal safety training for all frontline staff includes effective communication skills and use of the LEAPS (Listen, Empathise, Ask, Paraphrase, Summarise) de-escalation model.

The workforce understands how to use stop and search powers fairly and respectfully

All police officers have initial training in using stop and search powers, which is refreshed in annual personal safety training. The force requires stop and search interactions to be video recorded on body-worn cameras. We reviewed a sample of 184 stop and search records from incidents between 1 January and 31 December 2020 and concluded that reasonable grounds were evident in 87.5 percent (with a confidence interval of +/- 4.7 percent). This is lower than our review the previous year when we estimated that 91.5 percent (with a confidence interval of +/- 3.5 percent) of stop and searches had reasonable grounds. Reasonable grounds were evident for 26 of the 28 searches of people of Black, Asian or minority ethnic backgrounds that we reviewed.

The force understands and improves the way it uses stop and search powers

The force uses an effective external scrutiny process to understand and monitor its use of stop and search. The stop and search scrutiny panel of the independent police advisory group (IPAG) has diverse representation from throughout the community and is provided with comprehensive information and data on stop and search. This information is also available on the force’s website. Video footage of stop and search incidents has been presented to the group, stimulating constructive challenge and debate.

Internally, the force has an effective monitoring process through stop and search champions. Each champion conducts a monthly review of 20 searches chosen at random. They review body-worn camera footage and body language, as well as the location and conduct of the search. They determine the common themes for learning and development and refer any incidents of concern for further investigation. The force acknowledges that currently there is lack of internal strategic oversight and data monitoring for both stop search and use of force. A policing powers oversight board has recently been set up to respond to these concerns.

The workforce understands how to use force fairly and appropriately

All student officers have tuition in personal safety, de-escalation techniques and the use of force as part of their initial training, which is refreshed annually. During the pandemic, the force took effective distancing measures to ensure this training could continue. A mandatory form is filled out immediately by officers when force is used and is effectively reviewed by a supervising officer.

The force understands and improves the way in which it uses force

Kent Police effectively monitors its use of force in a similar way to stop and search through the external IPAG. The force provides the group with good data and information, including the number of times taser is used. This information is also available on the force’s website. Internally, the lack of strategic oversight is being rectified by the introduction of the policing powers oversight board.

Good

Preventing crime and anti-social behaviour

Kent Police is good at prevention and deterrence.

Main findings

In this section, we set out our main findings that relate to prevention and deterrence.

The force prioritises the prevention of crime, anti-social behaviour and vulnerability

These priorities are set out clearly in the force’s policing plan with effective strategic oversight through the monthly local policing and harm prevention board. There are a range of neighbourhood policing teams under the umbrella name of community safety units. The force told us that its dedicated town centre policing teams total 56 officers in more than 20 locations. These teams work well with local authorities and organisations to identify and resolve the community’s concerns and tackle persistent offenders through a range of prevention and enforcement measures, such as criminal behaviour orders. Local priorities are linked into force priorities through an effective tasking process.

The force’s operating model is built upon identifying the most vulnerable in the community and positively intervening to reduce risk and harm. The force has invested significantly in early intervention for vulnerable children, provided through its child centred policing plan. It has recently created a dedicated team of officers for schools to improve the work it does with young people, identifying and preventing harm or criminality at an early stage. This includes those who are vulnerable to serious violence, gang exploitation and involvement in county lines drugs distribution. The Kent and Medway Violence Reduction Unit, composed of police and other organisations, has adopted a public health approach to addressing the causes of serious youth violence and aims to intervene early to support those at risk. For example, it supports the voluntary use of smart tags that electronically track individuals who feel at risk of exploitation.

The force has an effective approach to preventing crime, anti-social behaviour and vulnerability

The force effectively uses the OSARA model – objective, scanning, analysis, response, assessment – to identify and address issues in its communities. Each district has a crime prevention and demand reduction PCSO to advise on local problems and solutions. They support officers and staff in the creation, management and evaluation of OSARA plans. Community safety teams are co-located with relevant council teams to jointly respond to issues such as anti-social behaviour, rough sleeping and the night-time economy. In one, university campuses were visited to provide returning students with crime prevention advice and followed up with night-time patrols to identify and support those who are potentially vulnerable.

The force, with other allied organisations and supported by the Office of the Police and Crime Commissioner, has set up three multi-agency task forces to tackle crime, prevent violence and safeguard those most vulnerable in the community. They focus on areas with disproportionally high levels of crime and anti-social behaviour. The force told us that the Medway task force recently visited 1,100 addresses, gave out 574 crime prevention advice packs and made sure that there were support visits from other organisations, such as mental health charities, where needed. The task forces will also proactively target persistent offenders across a wide range of crimes.

The force needs to better understand demand on neighbourhood policing teams so that it can manage its resources more effectively

In the year ending 31 March 2021, the force spent approximately 23 percent of its budget on neighbourhood policing. This figure is significantly above average compared to other forces but includes response officers who are referred to as local policing teams. These officers are expected to work with their communities to identify and resolve issues, but they rarely have time. In fact, such is the demand placed on them, sometimes the community safety units have to respond to calls to support them. This reduces their collaboration work, such as visits to vulnerable victims or attending community meetings. Equally, town centre policing teams are regularly assigned to other operational duties, such as arresting wanted suspects, which reduces their visibility within town centres.

The force makes good use of volunteers to support its initiatives. Its special constabulary plays an important role in protecting and serving the public. The force told us that special constables worked 12,000 fewer volunteer hours in 2020 than the previous year, but it is anticipated that these will return to pre-pandemic levels, helped by an increase in special constables from 284 in 2019/20 to 348 in 2020/21.

Good

Responding to the public

Kent Police requires improvement at responding to the public.

Main findings

The force needs to do more to fully identify and understand risk at initial contact

The force normally answers calls from the public promptly within its force control and incident response (FCIR). It regularly achieves, or exceeds, the national target time for answering 999 and 101 calls. Members of the public can also contact the force through an online chat service, the use of which increased during the pandemic. All contact management staff are trained in applying the THRIVE assessment of vulnerability and were found to be polite and professional when speaking to callers. However, where THRIVE was recorded it was often too brief, meaning that the full extent of a victim’s vulnerability may not be evident.

The force has introduced a ‘vulnerability hub’ offering specialist support for its response to domestic abuse victims. Although currently working only limited hours, this team researches live incidents to provide attending officers with as much information as possible. The team speaks directly to domestic abuse victims by phone when it has been assessed that an immediate response isn’t required. This enables them to provide early support and advise that evidence is to be collected at the earliest opportunity.

The force is good at identifying signs of vulnerability when it responds to incidents

Officers look for signs of vulnerability when they attend incidents, for example children exposed to domestic abuse or any signs of exploitation. Any vulnerability identified is flagged up on the force’s crime reporting system. Officers are clear on their responsibilities to safeguard vulnerable people.

Officers generally have a good knowledge of crime scene principles to ensure evidence is preserved.

Officers responding to people in mental health crisis have access to advice and guidance from specialist practitioners through a dedicated helpline. This allows the force to provide prompt support and intervention and often reduces the need to resort to police powers under section 136 of the Mental Health Act to detain people for their own safety.

The force doesn’t properly understand the level of demand for responses from the police

Response officers, known as local policing teams, benefit from having a range of roles. They investigate certain types of crime, complete case papers and respond to calls. However, the number of officers and the level of skill and experience on these teams is insufficient to meet demand.

A process that enables districts to set resources below minimum strength and draw additional resources from neighbouring districts allows the force to flex resources to meet demand. However, the force doesn’t fully understand the wider effect of this process. Support is inconsistent and leads to delays for victims. The pressure on resources also means that the force isn’t always effectively managing crime scenes to make the most of early opportunities to collect evidence and carry out initial investigations. This will impact on both the service provided to victims and staff safety and wellbeing.

The force understands the wellbeing needs of its control room staff and officers responding to emergency calls

Both control room staff and the local policing teams deployed to incidents receive good levels of welfare support via the TRiM trauma management process, online support and the availability of counselling.

The chief officer team views officer safety as a priority. The force has a nine-point plan to provide enhanced support to any officers or staff who have been assaulted. It has a clear ethos that being a victim of crime will “never be seen as just part of the job”.

The FCIR runs a departmental ‘culture board’ that enables staff at all levels to come together as equals and raise issues. It focuses on responding to the environmental and psychological needs of staff at an early stage. Workshops encourage staff to face and solve problems. Joint control room and response team meetings promote positive working relations between the two departments to provide a quality service.

The force has recognised its control room’s specialist training needs and an in-house unit introduced in April 2020 conducts initial training and oversees continual professional development. A quality assurance officer also works with each team. They randomly test calls and offer coaching where needed. Learning themes are fed to the operational review committee for discussion and dissemination.

The force told us that a significant number of student officers have been posted to frontline local policing teams. This increase in staffing provides further resilience but having limited capabilities, such as police driving or taser authority, restricts when they can be deployed and their effectiveness. The training courses they need have been delayed due to the pandemic. Plans to increase course availability in the next 12–18 months should ensure that officers receive the additional skills needed to improve their capability to respond to incidents.

Requires improvement

Investigating crime

Kent Police requires improvement at investigating crime.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force investigates crime.

The force understands how to carry out quality investigations on behalf of victims and their families

The force recognises the difficulties it faces in terms of improving the quality of investigations. It has introduced a crime management and investigative quality board, chaired by the assistant chief constable, which meets monthly to review identified areas for improvement.

The board is supported by a set of clear standards that require supervisors to use an audit process to identify any poor practices that don’t meet them. This is further underpinned by an effective crime investigation policy that states clearly what investigators and supervisors need to do to progress and oversee investigations.

Investigations are sometimes affected by the delayed allocation of crimes and by a shortage of trained detectives

The investigation management unit makes an early assessment of whether a crime report needs further investigation, including a discussion with the victim. The force also uses artificial intelligence to support this process through EBIT (evidence-based investigation tool) for certain low-level crimes, such as criminal damage. This produces a probability score of a crime’s solvability.

In the cases we examined, decisions that crimes should be investigated were correct and in accordance with force policy. However, we found some incorrect decisions where a crime wasn’t subject to further investigation, one relating to a repeat vulnerable victim and others where there was potentially CCTV evidence.

We also found delays in applying both EBIT and other quality assurances processes, slowing down the allocation of crimes to an officer. Such delays reduce the opportunity to recover further evidence, such as CCTV. It may also lead to a loss of confidence in police by victims, who may ultimately withdraw from the process.

Having allocated crimes for further investigation, the force is also facing a significant shortage of trained detectives. It has taken steps to improve external recruitment through the Investigate First pathway, a fast track detective programme run by Kent and Essex Police. Equally, recognition of the importance of the role of detective has been improved through the use of bonus payments and the establishment of a dedicated crime academy offering continuing professional development.

Within the teams who deal with all domestic abuse investigations, the optimum level of PIP2 accredited detectives is set at 25 percent. It is of concern that the ratio is less than 5 percent force-wide, although Kent Police is taking immediate steps to increase detective capability within these units.

The force needs to provide a higher quality service to victims of crime

Of the 70 crime investigations reviewed, investigation plans were created in just under two thirds of applicable cases (34 of 54), with many lacking necessary detail and direction. In 19 of the 70 cases we found that not all investigative opportunities were taken from the beginning and throughout the investigation. We identified missed opportunities in over a quarter of cases. Examples included a report that a 13-year-old girl had been coerced into sending indecent images of herself, but the suspect wasn’t interviewed. There was a report of serious assault where the suspect was identified but never interviewed. In this case, the victim eventually withdrew support for reasons not documented. In most cases where opportunities were missed there was insufficient or no supervision and often poor or no investigation plans.

The force often doesn’t take opportunities to pursue offenders when victims disengage or fail to support prosecutions. In September 2020, the force published a standard operating procedure for evidence-led prosecutions, which don’t require the support of the victim. This pre-dates our inspection period, suggesting that it hasn’t had the necessary effect. The force’s own audit in December 2020 shows that only 1.2 percent of domestic abuse-related crimes where the victim didn’t support police action were considered for an evidence-led prosecution. Training is underway to support supervisors to ensure that opportunities for evidence-led prosecutions are considered.

For the year ending 31 March 2020, in Kent 65.3 percent of offences classified as domestic abuse were assigned with the code ‘outcome 16’. This is where an investigation hasn’t continued when a suspect is identified, but there isn’t enough evidence, and the victim has withdrawn their support for a prosecution. This was significantly higher than the average throughout forces in England and Wales (55 percent).

Proportion of offences classified as domestic abuse, recorded in the year ending 31 March 2020 with an outcome of ‘evidential difficulties: suspect identified; victim does not support further action’ (outcome 16)

Under the Code of Practice for Victims, there is a requirement to conduct a needs assessment at an early stage. This determines whether victims fall into one of three priority categories: victims of the most serious crimes, persistently targeted victims, and vulnerable or intimidated victims. Special measures can be used to support these victims to give the best evidence in court and these should be explained. The outcome of the assessment and the request for special measures should be recorded. We found no structure in place to ensure that victim needs assessments are completed and they were completed in less than a fifth of the cases we reviewed.

We examined a number of completed investigations where the force had recorded a named suspect, but the victim was said to have chosen not to support the investigation or a prosecution. We only found evidence of this withdrawal of support, such as a statement, body-worn video or pocket notebook entry, in one quarter of cases. In the others, the recorded outcome may not be properly representative of the victim’s wishes.

The force needs to improve the way it manages the wellbeing of staff involved in investigations

Kent Police has processes in place to support staff through access to online and telephone counselling and wellbeing services. There is signposting to services on the force intranet, but it needs to do more to ensure that frontline supervisors are properly considering the needs of staff, many of whom are junior and inexperienced, have high workloads and may be dealing with cases involving traumatised victims.

Supervisors hold regular meetings with their staff to discuss case progression but are rarely asking questions relating to welfare. Staff within CID and the vulnerability investigation teams have indicated that they are suffering from stress and anxiety, which is having a detrimental effect on their wellbeing and their performance. Earlier identification of these issues will aid timely intervention where appropriate and by extension improve the service provided to the public.

Requires improvement

Protecting vulnerable people

Kent Police is adequate at protecting vulnerable people.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force protects vulnerable people.

The force understands the nature and scale of vulnerability

The force has a thorough system of strategic governance in place at both force and divisional level. It aims to achieve a collective understanding of vulnerability, highlight and mitigate risk, implement and disseminate information about good professional procedures and plan activity that will respond to the needs of the full range of vulnerable people.

The force introduced an operating model known as New Horizon in September 2017, which involved moving a large number of officers into newly formed vulnerability investigation teams focused on vulnerable victims. The model is constantly evolving in line with improved awareness of the complexity and scale of vulnerability. For example, the force now has a dedicated domestic abuse and stalking strategic manager to ensure staff are trained in the use of preventative powers and orders through a mandated programme.

The force safeguards and supports vulnerable people, including those at risk of criminal exploitation, but stalking investigations could be improved

At the start of the pandemic the force raised awareness among the public of the increased risk of domestic abuse during lockdown and the support available to victims. This included proactive visits to high-risk repeat victims if analysis indicated that they had not recently reported an incident. The force continues to provide this data to divisions for them to make interventions.

In 2019, Kent Police, working with the College of Policing, introduced a new risk assessment tool (DARA) to enhance its focus on stalking, harassment and controlling and coercive behaviour. This helps officers and staff to proactively identify patterns of behaviour, which in turn leads to the identification of crimes such as stalking that otherwise would have gone unreported.

The force has established the multi-agency stalking intervention panel (MASIP), which enables investigators to refer high-risk stalking cases for legal advice on obtaining a stalking prevention order (SPO). The force has one of the highest rates for SPOs applied for throughout England and Wales.[1] The MASIP is a positive and innovative development, but it can only manage a relatively small number of cases. We reviewed several of its investigations and found that some weren’t timely or effective, which meant that victims continued to be subject to abuse and some disengaged from the police. An effective investigation at an earlier stage may have resulted in court proceedings, negating the need to consider preventative orders.

The force has established missing and child exploitation teams on each division to work closely with vulnerable children, young people and their families in putting effective measures in place, reducing the number of episodes of missing children and lowering the risks associated with child exploitation. The team works closely with the force’s highly successful and proactive county lines and gangs teams. It works with external organisations to identify, disrupt and arrest organised criminals, making use of existing legislation, orders and notifications to not only protect the victim, but to ensure that the wider public remains safe.

[1] BBC Shared Data Unit: number of SPOs applied for from January to December 2020.

The force works with other organisations to keep vulnerable people safe

A central referral unit (CRU) fulfils a similar function to a multi-agency safeguarding hub (MASH) covering all of Kent except the unitary authority of Medway, which has its own MASH. The force doesn’t use referral forms for children or vulnerable adults coming to notice. Instead, these cases are made aware of by staff on the force’s crime and incident recording system. CRU officers and staff trained in safeguarding and risk assessment review them to ensure the right information is shared and the appropriate response provided. The force has introduced new processes so that there is a simpler and more effective identification of high-risk cases to improve the safeguarding response further.

Multi-agency risk assessment conferences manage the victims of domestic abuse most at risk. During our inspection, many of these meetings were held using video-conferencing technology. We were told that this meant that more people from other organisations attended and took part. We observed several of these virtual meetings and were impressed to see that a wide range of participants from other organisations were present. Information was shared effectively and constructive discussions led to steps being taken to keep victims safe.

The force has effective processes in place to obtain feedback from victims of hate crime, domestic abuse and rape. The survey responses are overwhelmingly positive. The figures are broken down at district and divisional level in quarterly reports and presented at the force performance management committee to help it to determine the opportunities to improve the service.

The force has worked constructively with other safeguarding organisations to implement Operation Encompass, nationally recognised professional standards in which police officers notify schools about domestic abuse incidents affecting children. The scheme has been well received and widely adopted throughout Kent. The force recently introduced Operation Encompass Plus to include other incidents affecting children beyond domestic abuse situations, such as missing children episodes and child exploitation concerns. This is a positive venture that promotes children’s welfare and works with wider safeguarding organisations.

Overall, the force has a good understanding of demand and resources, but it needs to improve the resourcing of domestic abuse teams

The force’s difficult staffing shortages in the teams that investigate domestic abuse have already been documented. Other units dealing with vulnerable victims are better resourced. The force recently introduced dedicated rape investigation teams and specialist vulnerable adult and child protection teams. Our review found that these teams consisted of suitably trained and qualified investigators with manageable workloads.

Adequate

Managing offenders and suspects

Kent Police requires improvement at managing offenders and suspects

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force manages offenders and suspects.

The force needs to improve its ability to arrest and manage suspects and offenders to protect the public from harm

Protecting vulnerable people boards meet monthly on each division to co-ordinate and prioritise activity against offenders based on risk. The force uses a predictive analytical product, Operation Herald, to support this process and ensure it is focusing on the offenders causing most harm. Proactive units target wanted offenders, but team numbers are low and the number of wanted offenders remains consistently high.

The force has a policy to manage police bail, including when suspects are released while under investigation. This includes a presumption that police bail with conditions will be imposed if a suspect has been arrested in connection with an offence involving vulnerable victims or domestic abuse. While this process maximises the opportunity to protect victims, the force needs to be sure that investigators optimise the initial period in custody and don’t release the suspect too quickly. Currently bail rates, especially for domestic abuse, are high. The force told us that in the year ending March 2021, there were 675 uses of pre-charge bail per 1,000 arrests related to domestic abuse. Consequently, opportunities to charge and bring offenders to justice may be being missed.

The force maintains strategic oversight of those who are bailed or released while under investigation through the victims’ justice board. Rates are monitored. Management of suspects released on bail or under investigation rests initially with frontline supervisors, who are required to review investigations within set timescales. Bail cases are generally supervised well, but there is a lack of oversight and often significant delays for suspects released under investigation. Many wait beyond six months for their investigations to be concluded.

The force needs to improve the way it manages the risk posed to the public by the most dangerous offenders

Responsibility for the management of registered sex offenders (MOSOVO) in Kent is held by two teams. A central team holds responsibility for reviewing violent and sex offender register (ViSOR) standards, policy and practice, and oversees performance management data. Operationally, divisional ViSOR teams manage registered sexual offenders. The central team’s clear expectations aren’t always met locally. Most notably, this is resulting in visit delays, including for the highest risk offenders, and delays in the completion and review of risk assessment and mitigation plans.

The force predominantly adheres to authorised professional practice (APP) guidelines for the management of these offenders. A local point of contact oversees lower-risk sex offenders who aren’t deemed to require proactive management, such as home visits. Eligibility for that status is in line with APP. The annual review of these offenders is comprehensive. There is clear oversight and involvement with MAPPA alongside a strong understanding of the serious further offence process.

Sexual harm prevention orders (SHPOs) are routinely applied to offenders and variations are applied for where needed. Breaches are recorded for investigation, but the effectiveness of the response varies across divisions. Technology to support the management of SHPOs is underused due to the capability and capacity of staff. As a result, the orders aren’t as well managed as they could be, which reduces opportunities to proactively identify breaches of orders and further offending.

Three paedophile online investigation teams, one per division, oversee all elements of child abuse image investigation. The teams don’t have the technology to review computers at the scene of an incident. However, they can review phones and tablets without having to send them to the force’s digital forensic unit, where there are significant processing backlogs, albeit high-risk cases are prioritised. Staff awareness on retrieving evidence from storage in the cloud could be improved. Access to cloud storage can be requested by the digital forensic unit, but vital evidence could be deleted by the time the device is reviewed.

The force uses the national child abuse image database (CAID), which helps police detect, highlight and analyse illegal digital images. It is the responsibility of the victim identification team to upload graded images. Where possible, the team will develop intelligence to try to identify the child. Staff raised concerns about backlogs in image uploads to the CAID system. They suggested that some images aren’t uploaded because the force’s IT infrastructure isn’t always compatible with CAID system updates. This could lead to missed opportunities to safeguard children and bring their abusers to justice.

Community safety units (CSUs) are aware of registered sex offenders in their area. All divisional offender management teams create monthly presentations highlighting the highest risk ViSOR offenders. Pictures are included and shared with CSUs with a request for intelligence. The process is reported to yield positive results.

The force has an effective programme to manage people most likely to re-offend

The Kent and Medway integrated offender management (IOM) plan focuses on a fixed cohort of people responsible for neighbourhood crime. In line with recent government changes, IOM has become part of the strategic partnership command of police and other organisations, such as probation and housing, and is managed centrally. The aim is to bring together a range of organisations to effectively supervise offenders in the community through rehabilitative interventions and swift enforcement where needed. Operationally, monthly offender management meetings continue on division. There is good attendance from other allied organisations and effective information sharing supports offenders with complex needs. Offenders aren’t removed from IOM prematurely when they need support to change their behaviour, such as access job opportunities and training.

As domestic abuse offenders have been moved out of the IOM, the force has recently set up a multi-agency tasking and co-ordination (MATAC) process. Regular meetings of police and allied organisations assess and plan a bespoke set of interventions to target and disrupt serial domestic abusers or support them in addressing their behaviour. It is too early to assess whether this is reducing re-offending.

Requires improvement

Disrupting serious organised crime

Kent Police is good at tackling serious and organised crime (SOC).

Understanding SOC and setting priorities to tackle it

The force has effective strategic management and governance to manage SOC activity

The force has effective governance to manage the response to SOC. This includes meetings at strategic and operational levels where officers are held to account for their plans and offered support when required.

The force makes use of intelligence to identify, understand and prioritise SOC and inform effective decision-making

The force has a good understanding of the threat from SOC and has the resources to collect and analyse intelligence. It has developed its SOC strategic assessment from a range of intelligence sources.

The force doesn’t use MoRiLE on the SOC master list to assess all threats, for example some county lines groups. It uses another method to assess them, which means it is managing much more demand than is recorded on the SOC master list. We understand that the force takes this approach to reduce the bureaucracy in managing these groups in a small number of cases.

The force has introduced a portal through which partner organisations can submit intelligence directly. It also gives partner organisations quarterly presentations explaining local organised crime threats.

There are two multi-agency hubs, located in Folkestone and Dover. The force works with agencies, such as Border Force and UK Visas and Immigration, to share information and develop its response to immigration crime, including corruption at the border.

The force has improved how it includes local policing in its response to SOC. Frontline staff are provided with up-to-date information to increase their understanding of active local OCGs. During our interviews it was evident that staff from community policing teams understood how their role in disrupting SOC was linked to force priorities.

The force seeks to review its SOC operations to understand how it can improve and develop best practice

Operations are subject to a structured debrief and learning is shared on Insight, the intranet site accessible to all force personnel. In the tactical tasking co-ordination group process, some time is dedicated to discussions about best practice and learning, which can be shared with operational leads. A force review team can also be asked to conduct more detailed operational reviews.

Resources and skills

The force is committed to developing staff so that it can effectively respond to both current and emerging threats

The force has worked with Essex Police to develop combined specialist teams to tackle SOC. This allows each force to operate largely without the need for additional support from the ROCU. However, the force maintains a good relationship with the ROCU and can access additional specialist support when required.

The force has identified its priority SOC threats. One priority area is MSHT. It established an MSHT team in 2019 to respond to this threat, improve the understanding among frontline officers of safeguarding and vulnerability, and involve key partner organisations.

LROs are largely supported in their role

The force allocates SOC threats to chief inspectors who take on the role of LRO. They develop 4P plans to target an SOC threat with the assistance of specialist capabilities and relevant local partner organisations. The force has introduced the role of OCG co-ordinator, to support LROs with their 4P plans and give tactical advice.

LROs have an informal network to give each other support and advice when appropriate. The force has no specific training for LROs but intends to fill this gap.

Tackling SOC and safeguarding people and communities

The force takes a problem-solving approach to tackling some SOC threats

In the year ending 31 May 2022, Kent Police led 168 disruptions involving SOC. This was 11 percent of all the disruptions in the eastern region and the third highest in the region. Twenty-five percent of disruptions were prevent or protect disruptions; the remainder were pursue.

We mentioned in the Regional findings section that some groups involved in criminal activity aren’t always assessed to see if they should be considered as an OCG. Kent Police is a case in point. The force uses a problem-solving process (OSARA) to tackle these groups. This is mainly carried out by community policing teams, who already use a problem-solving approach to tackle other neighbourhood problems.

Working with the PCC, the force has secured additional funding to tackle serious violent knife crime, which overlaps with the threat from county lines. As a result, the force works with partner organisations, such as the British Transport Police, to run knife arch operations at railway stations. (A knife arch is a walk-through metal detector, which can detect hidden knives.)

The force works effectively with partner organisations to safeguard those at risk of being involved in SOC

During our inspection, the force SOC partnership meeting was observed. 4P plans were presented and the identification of vulnerability and subsequent safeguarding in communities was discussed. The emphasis from the meeting was on protect, prepare and prevent activity, and what joint action could be taken with partner organisations (such as the fire and rescue service and HM Prison and Probation Service).

The force has introduced a protect and prevent lead, who works with police personnel and partner organisations to prevent SOC and protect victims. Force SIOs told us that engaging with the lead had improved how they tackled SOC.

We found that neighbourhood officers worked alongside staff from local authorities to support vulnerable members of the community. They also conduct school visits to try and prevent young people becoming involved in crime. Neighbourhood officers are generally aware of the national referral mechanism and could provide examples of using this to safeguard vulnerable people.

Read An inspection of the eastern regional response to serious and organised crime – May 2023

Good

Building, supporting and protecting the workforce

Kent Police is good at building and developing its workforce. In this section, we set out our main findings.

Main findings

The force promotes an ethical and inclusive culture at all levels

Kent Police promotes the Code of Ethics at every opportunity and its workforce receives advice and extensive training on ethical decision-making. As a result, officers and staff have an excellent understanding of ethical policing and confidence in raising concerns. Many of these are then discussed at the force ethics committee, with responses reported via its internal website.

The force’s culture board, chaired by the chief constable, and annual force culture conference help all staff to participate in shaping the organisation with the aim of achieving a working environment where staff flourish and have a sense of purpose. Support for the process is demonstrated by the wide range of culture boards that staff have set up spontaneously and which are an integral part of the working environment.

To support the force’s purpose, intentions, values and priorities, and to encourage innovation and creativity, the chief constable has introduced the ‘Infinity Principles’. They are considered fundamental in driving the organisation forward and they apply to everyone. The principles aim to remove boundaries that inhibit innovative thinking with success being measured by improvements to the service provided by the force. Officers and staff are encouraged to put forward new ideas or share information about good professional procedures through an online platform or through local culture boards.

The force develops effective strategies for improving its workforce’s wellbeing although some teams feel less supported

Although we have reported that some teams in the force are experiencing stress and feel unsupported by supervisors, overall, the force prioritises its workforce’s mental and physical wellbeing. It shows commitment to providing opportunities for employees to maintain their health, wellbeing and safety. A dedicated steering group of staff from different parts of the workforce meets monthly to take a lead on employee health and wellbeing. The health and safety board meets regularly to ensure that safe and appropriate workplace processes are developed and maintained. Representatives from staff associations and trade unions attend.

Kent Police demonstrates a commitment to reducing stigma about mental health. A network of well-publicised health and wellbeing champions provide a confidential service where colleagues talk about mental health problems and can signpost to other services if needed.

There is generally excellent support for staff experiencing trauma, mental ill-health or other difficulties. Supervisors have mandatory training in mental health support and the force has implemented a programme designed to equip managers and supervisors with the skills needed to support their teams and encourage staff to be more open. The force’s leadership academy provides programmes to support wellbeing. TRiM, a peer support network for people who have experienced trauma, is widely used and advertised. The force also has a disability network, Crystal Clear, which offers advice and support.

From the start of the pandemic, the force recognised its potential effect on the workforce, such as having to isolate, and implemented measures to ensure staff welfare is prioritised. Its online wellbeing sessions have been well used. It introduced an employee assistance programme health assessment for staff and their families.

This is a 24/7 helpline and one-to-one counselling free of charge for personal and work-related issues including bereavement, relationship problems, stress and trauma. Part of the efficacy of this process is a recognition that a third of sickness is due to non-work issues.

A human resources and wellbeing hub brings together important information, local policies, frequently asked questions and telephone services, as well as enabling staff to escalate worries to a senior manager.

The force is building its workforce for the future

The force has developed an interactive online platform so that candidates can monitor their progress through the recruitment process and it ensures they feel valued and informed. Its online Develop You portal provides a consistent and accessible suite of development tools to help all members of the force to take responsibility for their own learning and continuing professional development.

The force has made progress in recruiting from the full range of its diverse communities. A dedicated positive action team focuses on activity to improve the attraction, selection, development and retention of officers and staff with protected characteristics. It runs virtual and physical events and collaborates with national support networks to inform prospective candidates about the organisation. The force’s Investigate First programme, which offers accelerated access to detective roles, has been particularly successful in attracting and retaining talented staff from under-represented groups. They often move quickly on both leadership and specialist roles.

Kent Police recently launched a diversity and inclusion academy. This aims to co-ordinate and monitor the effectiveness of force diversity policies in relation to training and externally through its work with other organisations and its communities. A diversity and inclusion interview has been added to the promotion process, at which candidates are asked how they will value diversity, promote equality and facilitate inclusion for colleagues and the community.

A wide range of staff support groups including for race, religion, disability, gender, sexuality and other cultural differences, offer advice and support to employees and managers.

The force analyses why individuals leave the organisation, looking at ethnicity, gender, length of service, departments and geographical location. Exit interviews are an important part of this process.

Kent Police has very recently completed a force-wide survey, together with Christchurch University, focusing on structures and process, leadership and management, opportunities, resources and barriers and health and wellbeing. The main findings will be followed up with workshops. This timely and comprehensive survey should help the force to better assess how staff feel about the force in a range of important areas.

Good

Strategic planning, organisational management and value for money

Kent Police is good at operating efficiently.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force operates efficiently.

The force targets resources at its priorities

The force has an effective monthly tactical and tasking co-ordination group meeting, chaired at chief officer level. The meeting considers risks and provides updates on force priorities. These are in line with the force’s control plans, which set out and communicates the long-term operational priorities for the force in terms of crime prevention, enforcement and intelligence. We found that bids for additional funding or support were detailed and decisions on allocation of resources were based on the prioritisation of risk and harm, in line with the control plans.

The force’s policing plans aim to create a culture of prevention and early intervention throughout all frontline teams. However, local policing teams are included in the neighbourhood policing strength. This gives the impression there are more officers available to identify problems and solve them than exist.

The force has an experienced task force making sure it has the right resources to meet future needs

The innovation task force was introduced in January 2018 to look ahead, apply evidence-based policing techniques, conduct qualitative and quantitative research, and seek new processes and technology that could improve the service it provides to the public. It uses methods such as randomised control trials to test different policing approaches.

The force makes the best use of its funding and its plans are ambitious

The force has a clear plan to provide a balanced budget. Its Zenith change management programme includes the disposal of its headquarters. As well as achieving capital savings, the programme will permanently change the force’s policing activity so that it is more flexible and less reliant on capital assets.

The force told us that its plan has yet to be agreed, but if implemented it will produce savings of over £5m in 2021/22. However, a large proportion are related to reducing establishment levels and using the government-funded increase in officers to replace civilian staff. There is a risk that the initial savings identified will not be lasting.

Kent Police actively seeks opportunities to improve services by working effectively with other forces

The force has a well-established and effective collaborative process with Essex Police. An example is the prioritisation and optimisation of IT projects. Both forces have agreed an ambitious but realistic programme for digital development up to 2023/24.

The force can demonstrate it is continuing to achieve efficiency savings and improve productivity

Kent Police was one of the first forces nationally to roll out the Microsoft 365 technology in line with the national programme to create secure, cloud-based platforms. Staff have been given access to Microsoft Teams chat and collaboration tools such as SharePoint. This has enabled the force to significantly expand opportunities to work remotely, especially during the pandemic, often more efficiently.

Good

About the data

Data in this report is from a range of sources, including:

- Home Office;

- Office for National Statistics (ONS);

- our inspection fieldwork; and

- data we collected directly from all 43 police forces in England and Wales.

When we collected data directly from police forces, we took reasonable steps to agree the design of the data collection with forces and with other interested parties such as the Home Office. We gave forces several opportunities to quality assure and validate the data they gave us, to make sure it was accurate. We shared the submitted data with forces, so they could review their own and other forces’ data. This allowed them to analyse where data was notably different from other forces or internally inconsistent.

We set out the source of this report’s data below.

Methodology

Data in the report

British Transport Police was outside the scope of inspection. Any aggregated totals for England and Wales exclude British Transport Police data, so will differ from those published by the Home Office.

When other forces were unable to supply data, we mention this under the relevant sections below.

Outlier Lines

The dotted lines on the Bar Charts show one Standard Deviation (sd) above and below the unweighted mean across all forces. Where the distribution of the scores appears normally distributed, the sd is calculated in the normal way. If the forces are not normally distributed, the scores are transformed by taking logs and a Shapiro Wilks test performed to see if this creates a more normal distribution. If it does, the logged values are used to estimate the sd. If not, the sd is calculated using the normal values. Forces with scores more than 1 sd units from the mean (i.e. with Z-scores greater than 1, or less than -1) are considered as showing performance well above, or well below, average. These forces will be outside the dotted lines on the Bar Chart. Typically, 32% of forces will be above or below these lines for any given measure.

Population

For all uses of population as a denominator in our calculations, unless otherwise noted, we use ONS mid-2020 population estimates.

Survey of police workforce

We surveyed the police workforce across England and Wales, to understand their views on workloads, redeployment and how suitable their assigned tasks were. This survey was a non-statistical, voluntary sample so the results may not be representative of the workforce population. The number of responses per force varied. So we treated results with caution and didn’t use them to assess individual force performance. Instead, we identified themes that we could explore further during fieldwork.

Victim Service Assessment

Our victim service assessments (VSAs) will track a victim’s journey from reporting a crime to the police, through to outcome stage. All forces will be subjected to a VSA within our PEEL inspection programme. Some forces will be selected to additionally be tested on crime recording, in a way that ensures every force is assessed on its crime recording practices at least every three years.

Read the details of the technical methodology for the Victim Service Assessment.

Data sources

Domestic abuse outcomes

Domestic abuse outcome proportions show the percentage of domestic abuse crimes recorded in the 12 months ending 31 March 2020 that have been assigned each outcome. 28 police forces provided domestic abuse outcomes data through the Home Office data hub (HODH) every month. We collected this data directly from 14 forces, with Greater Manchester Police unable to provide data for all time periods in the year. This means that each crime is tracked or linked to its outcome. So this data is subject to change, as more crimes are assigned outcomes over time.

Domestic Violence Protection Orders

We collected this data directly from all 43 police forces in England and Wales, though not all forces could provide data. This data is as provided by forces in May 2021.