Overall summary

Our judgments

Our inspection assessed how good Dorset Police is in ten areas of policing. We make graded judgments in nine of these ten as follows:

We also inspected how effective a service Dorset Police gives to victims of crime. We don’t make a graded judgment in this overall area.

We set out our detailed findings about things the force is doing well and where the force should improve in the rest of this report.

Important changes to PEEL

In 2014, we introduced our police effectiveness, efficiency and legitimacy (PEEL) inspections, which assess the performance of all 43 police forces in England and Wales. Since then, we have been continuously adapting our approach and this year has seen the most significant changes yet.

We are moving to a more intelligence-led, continual assessment approach, rather than the annual PEEL inspections we used in previous years. For instance, we have integrated our rolling crime data integrity inspections into these PEEL assessments. Our PEEL victim service assessment will now include a crime data integrity element in at least every other assessment. We have also changed our approach to graded judgments. We now assess forces against the characteristics of good performance, set out in the PEEL Assessment Framework 2021/22, and we more clearly link our judgments to causes of concern and areas for improvement. We have also expanded our previous four-tier system of judgments to five tiers. As a result, we can state more precisely where we consider improvement is needed and highlight more effectively the best ways of doing things.

However, these changes mean that it isn’t possible to make direct comparisons between the grades awarded this year with those from previous PEEL inspections. A reduction in grade, particularly from good to adequate, does not necessarily mean that there has been a reduction in performance, unless we say so in the report.

HM Inspector’s observations

I am pleased with some aspects of the performance of Dorset Police in keeping people safe and reducing crime. I am satisfied with most other aspects of the force’s performance, but there are areas where it needs to improve.

These are the findings I consider most important from our assessments of the force over the last year.

The force needs to better meet the needs of victims when responding to and investigating crimes

Dorset Police has had a challenging year, which has led to higher demand for services. Despite oversight by senior leaders and welcome initiatives to protect the most vulnerable, some victims haven’t received the standard of service they are entitled to expect.

The force doesn’t always deal with non-emergency calls promptly. It doesn’t follow all investigative opportunities and it doesn’t always pay sufficient regard to the Code of Practice for Victims of Crime. This may contribute to more cases where the victim disengages from investigations and to fewer positive results. I encourage the force to better understand why, and at what point, victims disengage so it can see where it needs to make improvements.

The force is prioritising the prevention and deterrence of crime

Well-established neighbourhood teams work closely with their communities and allied organisations on preventative and problem-solving initiatives. Recent recruitment and improved structures, aligned to local authorities, strengthen these relationships and give more opportunities to prevent crime and tackle anti-social behaviour.

There is a better understanding of why there are disparities when searching people and using force, but the focus on this area needs to continue

The force has worked harder to engage with diverse groups, gaining a better understanding of why disparities endure, for Black people in particular. But there needs to be reassurance that those monitoring activities consider all relevant information and are making a difference.

The force has improved its efforts to manage offenders and suspects

Officers arrest suspects promptly and are supported by leaders to make sure they apply bail appropriately. Specialist teams manage repeat and high-harm offenders well, using early intervention and diversionary pathways to reduce offending and prevent crime. I am pleased with the force’s efforts to improve its capacity and capability to investigate online sexual offending, but we need reassurance that sufficient long-term provision is in place so that investigations are timely and that children stay safe.

The force achieves value for money but needs to manage risks sooner

The force identifies where it can use efficiencies and collaboration to make savings. It understands demands on its services through predictive modelling and reviews. I am encouraged by the force’s agile responses when faced with increasing and competing demands. But I urge it to explore ways of identifying and managing these risks sooner so that it can provide consistent services.

Members of the workforce are well trained and supported to do their jobs

Despite the challenges, the workforce is well supported, engaged and positive. Officers and staff view the force as a good place to work and have trust and confidence in their leaders. They have the tools and training to do their jobs properly, underpinned by a people strategy that focuses on wellbeing, recruitment, development and retention.

The force has put in place new structures, processes and standards over the past year, which should make it better equipped to investigate crime, identify vulnerable people and manage demand.

Wendy Williams

HM Inspector of Constabulary

Providing a service to the victims of crime

Victim service assessment

This section describes our assessment of the service victims receive from Dorset Police, from the point of reporting a crime through to the end result. As part of this assessment, we reviewed 130 case files as well as 20 cautions, community resolutions and cases where the victim does not support or has withdrawn support for police action. While this assessment is ungraded, it influences graded judgments in the other areas we have inspected.

The force answers emergency calls quickly, but it should improve the way it answers non-emergency calls and identifies repeat and vulnerable victims

When a victim contacts the police, it is important that their call is answered quickly and that the right information is recorded accurately on police systems. The caller should be spoken to in a professional manner. The information should be assessed, taking into consideration threat, harm, risk and vulnerability. And the victim should get appropriate safeguarding advice.

Although the force answers emergency calls quickly, it needs to improve the rate at which callers abandon non-emergency calls. Staff assess victim vulnerability, but they don’t identify all repeat and vulnerable victims.

Most emergency calls are answered promptly. Non-emergency calls sometimes go unanswered, leading to callers abandoning the call. When staff answer the calls, they assess the vulnerability of the victim using a structured process. But they don’t always record it well and they don’t always identify repeat and vulnerable victims. This means the force doesn’t always gather all the information it needs to decide what response the victim should have.

The force doesn’t always give victims information on crime prevention or advice on how to preserve evidence from crime scenes. This potentially leads to the loss of evidence that would support an investigation and to a missed opportunity to prevent further crimes being committed against the victim.

The force doesn’t always respond to calls for service quickly enough and it doesn’t always identify victims’ needs

A force should aim to respond to calls for service within its published time frames, based on the prioritisation given to the call. It should change call priority only if the original prioritisation is deemed inappropriate, or if further information suggests a change is needed. The response should take into consideration risk and victim vulnerability, including information obtained after the call.

The force doesn’t always respond to calls for service within its target times, which means it isn’t always meeting victims’ expectations. This is due to a lack of available staff. As a result, we found examples of victims disengaging because of the time the force took to respond to incidents. The lack of effective intervention from supervisors meant the force didn’t always take opportunities to improve the situation. However, staff made and attended scheduled appointments appropriately in response to other non-urgent calls.

The force allocates crimes to appropriate staff and promptly informs victims if their crime isn’t going to be investigated further

Police forces should have a policy to make sure crimes are allocated to appropriately trained officers or staff for investigation or, if appropriate, not investigated further. The policy should be applied consistently. The victim of the crime should be kept informed of the allocation and whether the crime is to be further investigated.

The force’s arrangements for allocating recorded crimes for investigation are in accordance with its policy. In all cases we examined, staff allocated the crime to the right department for further investigation. The force promptly updates victims to inform them if their crime report won’t be investigated further. This is important as it gives victims an appropriate level of service and manages expectations.

The force doesn’t always carry out effective investigations or have sufficient regard for victims’ needs

Police forces should investigate reported crimes quickly, proportionately and thoroughly. Victims should be kept updated about the investigation and the force should have effective governance arrangements to make sure investigation standards are high.

The force carries out most investigations in a timely manner. Although officers generally complete relevant and proportionate lines of enquiry, we did see occasions when they missed opportunities. We are concerned that these issues were most apparent in stalking and harassment cases. This shows that victims who are potentially at risk may not be receiving the service they deserve. The force needs to improve how it investigates stalking and harassment.

Investigations aren’t always appropriately supervised. And the force doesn’t always update victims often enough during investigations. A thorough investigation increases the likelihood of identifying perpetrators and helping the victim have a positive outcome. Victims are more likely to have confidence in a police investigation when the force updates them at main stages of the investigation.

The Code of Practice for Victims of Crime requires a needs assessment to be conducted at an early stage to decide whether victims need additional support. Forces should record the outcome of the assessment and the request for additional support. The force doesn’t always complete the victim needs assessment, which means not all victims get the right level of service.

The force finalises reports of crime appropriately, by considering the type of offence, the victim’s wishes and the offender’s background

The force should make sure it follows national guidance and rules for deciding the outcome of each report of crime. In deciding the outcome, the force should consider the nature of the crime, the offender and the victim. And the force should show the necessary leadership and culture to make sure the use of outcomes is appropriate.

In certain cases, offenders who are brought to justice can be dealt with by means of a caution or community resolution. This outcome must be appropriate for the offender and the force should take the views of the victim into consideration. In most of the cases we inspected, the offender met the national criteria for the use of these outcomes and the force sought and considered the victims’ views.

Where a suspect is identified but the victim doesn’t support police action, or withdraws support for it, the force should have an auditable record to confirm the victim’s decision so it can close the investigation. There was no evidence of the victim’s decision in some of the force’s cases that we reviewed. This shows a risk that the force may not be fully representing and considering victims’ wishes before finalising crimes.

Engaging with and treating the public with fairness and respect

Dorset Police is adequate at treating people fairly and with respect.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to treating people fairly and with respect.

The force engages well with its communities

Dorset Police takes an inclusive, appropriately tailored approach to engaging with the public, considering all elements of the community, main partners and community contacts.

This is important as it helps the force understand the needs of all its communities. Work with local people takes place through neighbourhood police and community group meetings, a diverse community legitimacy group, and Prejudice Free Dorset (a group made up of local organisations that seeks to promote inclusive communities throughout the county, challenging prejudice so people can live safely and with confidence).

The force uses a wide range of media channels to broadcast and obtain information and respond to the public. Accepted neighbourhood policing teams (NPTs), specialist engagement officers and volunteers carry out more traditional face-to-face interaction and engage with the public. For example, they use ‘street corner’ meetings and crime prevention initiatives as part of many well-developed volunteering activities.

We found evidence of NPTs and other parts of the force engaging with diverse groups. A good example is the work they do with a charity called It’s All About Culture, based in a community hub in Boscombe, which aims to support, engage with and learn from the community. The force’s positive action team runs weekly sessions at the hub that encourage work with local people and provide information about joining the force.

The force captures the public’s views through regular and themed surveys, main community contacts and well-developed partnerships. It shapes priorities using information it gains through surveys, targeted activities working with local people, and intelligence, together with its own threat assessments. This builds public confidence with seldom-heard groups.

The force understands how to treat the public with fairness and respect and why it should do so

There is an emphasis on leaders and supervisors promoting fair behaviours and positive values. The force considers fair treatment to be important. It shows this by providing unconscious bias training, communication training (including empathy and active listening) and mentoring for senior officers. Chief officers oversee all aspects of equality, diversity and inclusion. And themes of fairness and respect are woven into comprehensive training and continuous professional development for teams throughout the force.

Members of the workforce we spoke to understand expectations and feel comfortable challenging unfair behaviours. The force is strengthening positive values through ‘bystander’ training, designed to give the workforce the confidence to intervene more readily. This means officers and staff are more likely to apply these values during interactions with the public and they are more likely to be treated fairly.

Officers mostly understand and use stop and search powers fairly, but the force needs to give training to all frontline officers to maintain standards

The force has carried out significant data analysis and scrutiny to understand if it is using stop and search powers fairly. This has been at a team, individual and new‑starter level. To help maintain standards, the force gives training for new recruits, bespoke packages for existing staff and essential provision during annual officer safety training. But it recognises the need to refresh training for all frontline staff. This is planned for 2022.

A person who is searched is entitled to know what information or circumstances caused the officer to genuinely suspect they were in possession of the item being sought. So it is important that these grounds are present and officers accurately record and convey them.

During our inspection, we reviewed a sample of 204 stop and search records from 1 January to 31 December 2020. Based on this sample, we estimate that 82.8 percent (with a confidence interval of +/- 5.0 percent) of stop and searches carried out by the force during this period had reasonable grounds. This is a statistically significant decrease since our review the previous year, when we found that an estimated 93.7 percent (with a confidence interval of +/- 3.1 percent) of stop and searches had reasonable grounds. Of the 30 records that we reviewed for stop and searches on Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) individuals, 21 had reasonable grounds recorded. Closer supervision and consistent review of BWV will raise standards and communities will feel more confident that the force is treating them fairly.

The force understands and improves the way it uses stop and search powers

The force has enduring disparities in the use of stop and search for different ethnicities based on its resident population. In the year ending 31 March 2020, people who identified as Black or Black British were 22.5 times more likely than people who identified as white to be stopped by Dorset Police. Analysis to better understand and act upon this has included:

- exploring hypotheses relating to the number of visitors who may temporarily make the community more diverse;

- considering the potential effect of county lines drug dealers coming from cities with a more diverse population; and

- outdated census data from 2011.

Academic research with the Cambridge Centre for Evidence-Based Policing has let the force start trialling more targeted stop and search on a risk-assessed basis to reduce serious violence. This has been helped by an external company mapping the resident population, giving the force a detailed breakdown of population diversity in different areas.

Thematic reviews have considered the use of powers by individual officers and according to location and type of search data. This includes officers who use stop and search and those persons repeatedly searched. The reviews have resulted in changes to the way the force trains new officers. And where the force has identified a need as a result of the reviews, it has given some officers further training. Stop and search champions can give advice and improve the way officers use stop and search.

The force has both strategic and tactical boards to monitor the way officers conduct stop and search. It now considers and publishes a comprehensive set of data, including analysis and understanding of the reasons for disparities. The force has worked hard to ensure the ethnicity data its officers record is accurate. This is supported by officers using handheld devices to record data more easily.

A panel managed by the office of the police and crime commissioner gives external scrutiny and considers the way officers use stop and search powers. Recently the force has also developed its own community legitimacy group with a small but diverse membership. We encourage the force to build on and support recruitment for all external scrutiny panels. Having diverse panels, and giving them the right information to carry out their role, will help maintain public confidence.

Overall, the force has done more than at any other time to understand the reasons for the disparities it has identified, as well as acting to reduce them. This has rightly been driven by chief officers. It is important that this senior leadership is rigorous and that chief officers take all opportunities to give reassurance that the force treats everyone fairly and respectfully.

Officers are appropriately trained in the use of force

Officers receive regular training in the use of force and this complies with national standards. The force monitors its training, making sure it is relevant and current for all officers. And officers consistently complete use of force forms. The force assesses some of these forms for certain categories of use and against different groups of people. Further developing internal monitoring processes will improve the force’s understanding of any disparities that exist.

Adequate

Preventing crime and anti-social behaviour

Dorset Police is good at prevention and deterrence.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to prevention and deterrence.

The force prioritises the prevention of crime, anti-social behaviour and vulnerability

Dorset is one of the safest places to live in England and Wales. In the year ending March 2021, Dorset had a crime severity score of 9.9, compared to an average score throughout forces in England and Wales of 12.3. This means victims of crime in Dorset experience (on average) less serious crime than victims in other force areas.

The force has an effective and visible neighbourhood policing model made up of police officers, community support officers and community safety accredited staff. They work together with other bodies such as health, housing and education to tackle community priorities. Senior leaders oversee neighbourhood policing well. There is a focus on the nationally recognised College of Policing pillars of engagement, intervention and problem-solving. Local and force-level meetings monitor the performance of neighbourhood teams.

The force recently introduced a new performance framework to underpin this approach. Encouraging all staff and supervisors to work within this new framework will build on this position and allow the force to better evaluate what works.

The force implements neighbourhood policing plans in consultation with other organisations and the community

Consulting with its communities helps the force understand what is important and to balance its response appropriately with addressing other priorities. The force tailors neighbourhood ‘engagement contracts’ according to area and publishes them on its website. To inform the contracts, the force uses bespoke surveys, consultation with main community contacts, and local and strategic partnership meetings.

The force aligns its priorities to the Dorset Police and Crime Plan. There is particular emphasis on preventative action to protect vulnerable people and on tackling anti-social behaviour (ASB). We saw an example in Operation Relentless – a force-wide approach to dealing with ASB when it was particularly high during the pandemic in summer 2021.

The force has increased its use of preventative orders to reduce nuisance and dangerous behaviour caused by large gatherings. And effective analysis of knife crime in Dorset means the force can deploy proactive officers in the best way to tackle the threat of these crimes. This reduces risk in the community.

A dedicated safer schools team prioritises interventions with children. The team also engages with teachers and provides learning packages and support for those most likely to come to harm or be criminally exploited. A team of officers works closely with other organisations to target travelling drug dealers. These criminals exploit children and prey on vulnerable people, often using their homes as bases for their offending. Consulting and working closely with other organisations allows the force to deal more effectively with community priorities.

The force understands community strengths and needs

Neighbourhood policing teams (NPTs) consider the needs of all their communities. This includes elderly victims of fraud, BAME and LGBTQ+ victims of hate crime, and young people. Neighbourhood engagement officers and a positive action team find out about a wide range of cultural, religious and community events and celebrations where targeted activity will be useful. Staff complete engagement calendars, which are evaluated to understand the reach and effectiveness of interactions.

The force has an extensive volunteer network, which includes special constables and cadets. These volunteers lead crime prevention activities and run workshops with young adults at colleges. Other volunteers co-ordinate community crime-reduction activity such as Community Speedwatch, Hotel Watch and Neighbourhood Watch.

We found that police community support officers (PCSOs) are enthusiastic and many have been in their roles for a long time. As a result, they have extensive knowledge of their communities and know which organisations to contact to address particular problems. For example, we saw a project involving local communities to reduce fraud against older people. Another example involved working with the local authority to give Afghan refugees basic essentials, signposting and reassurance. This allows staff to build trust, identify risks and better protect their communities.

The force uses evidence-based problem-solving approaches

Evidence-based policing creates, identifies and reviews the best available evidence to inform and promote good working methods and decisions. This means accepted practices can be challenged, innovation can take place and forces can improve performance. Leaders at Dorset Police learn about, promote and share information about good working methods through an external academic partnership group, internal forums, a ‘lessons learned’ newsletter and other force-wide communications.

The force works closely with Bournemouth University to research and make use of the most effective crime-reduction approaches. Evidence-based approaches receive innovation funding and officers and staff can develop skills through the Cambridge Centre for Evidence-Based Policing.

Neighbourhood staff work with an extensive range of organisations to understand and solve root causes of problems and to protect vulnerable people. For example, PCSOs are integrated into a local authority project to improve opportunities for vulnerable young people at risk of going into local authority care. The force leads a project to support and reduce homelessness. It also engages in offender management programmes that tackle repeat domestic abuse perpetrators. The force evaluates these evidence-based initiatives to see where and how they bring about improvements. It can then more widely adopt those that result in reduction in crime, reduction in repeat offending and cost savings.

The force should further develop structured problem-solving at a local level and sharing of good ways of working

We saw some good examples of NPTs using structured problem-solving plans such as scanning, analysis, response and assessment (SARA). Developed with other organisations, these plans tackle enduring crime and ASB at important community locations such as bus stations, parks and seafronts. NPTs also participate in multi-agency risk-management meetings, which take a problem-solving approach. This ensures vulnerable victims receive support. But the force should make sure it uses structured problem-solving plans consistently at all locations.

When the force identifies good problem-solving practices locally, it retains and shares them through an intranet site. But leaders in Dorset should develop this practice and promote its use, as the force relies too much on local knowledge. This means it may be missing opportunities. Doing this will also encourage the force to better evaluate what works and adapt effective plans for similar problems. This would allow the force to use limited resources wisely.

The force is balancing neighbourhood demand with its available resources

Dorset Police sees the role of neighbourhood policing as integral to crime reduction and early intervention. The force has used a demand-reduction group to find out about neighbourhood resources, introduce safeguards and make sure it allocates tasks appropriately.

The force has ring-fenced neighbourhood policing resources and it has a policy that stops neighbourhood officers and staff being routinely taken away from their duties. Despite this, unusually high ‘staycation’ demand, COVID-19 absences and abstraction to national events meant that this was more prevalent than usual during the 2021 summer months. But a footprint of PCSOs and community safety accredited staff remained as a visible presence. (‘Abstraction’ means diversion for an extended period to duties that aren’t part of the officer’s main duties.)

To ensure a growing presence, and a focus on tackling ASB, the force has prioritised neighbourhood officers as part of the Government uplift in recruiting police officers. In the year ending 31 March 2021, Dorset spent 5.5 percent of its budget on neighbourhood policing. This is significantly less than the average throughout forces in England and Wales. Some increases in reported ASB may reflect this lower spend. In response to this and other threats to vulnerable people, the force has recently created neighbourhood enforcement teams to robustly tackle ASB, address vulnerability and prevent crime. This is positive and shows the importance the force places on this area of policing.

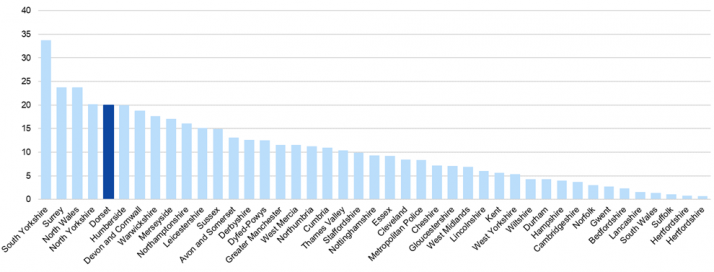

Percentage of force total budget spend on neighbourhood policing throughout forces in England and Wales in the year ending 31 March 2021

The force professionalises neighbourhood policing through training and development opportunities

Dorset Police has a professionalisation programme. In 2021, the force reviewed it to make sure it was still relevant and meeting the needs of its workforce. The programme includes an induction for all those who are starters in neighbourhood teams. This induction covers problem-solving, involving the community in projects and identifying and tackling vulnerability. The force gives its people laptops, handheld devices and up-to-date intelligence. There are regular continuous professional development days and activities. Officers and staff also take part in other modules, such as training on:

- vulnerability, with a focus on identifying hidden harm;

- seldom-heard groups;

- unconscious bias; and

- domestic abuse.

Members of teams we spoke to said many of the training events take place with partners. This is positive as it helps bring about consistent approaches from different organisations. This gives teams the tools and confidence to tackle issues relevant to their roles.

The force recognises and values those who perform well

The force has a culture of recognising and valuing the positive effects of neighbourhood policing activities, such as problem-solving and tackling ASB. It also recognises and rewards the contributions of volunteers and those in neighbourhood teams. We saw force-wide recognition for the most effective teams and for notable volunteering projects, including partnership initiatives.

Effective reward and recognition help members of the workforce feel valued by their senior leaders. Staff are also more likely to stay engaged in exploring crime prevention and deterrence activities for their communities.

Good

Responding to the public

Dorset Police requires improvement at responding to the public.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force responds to the public.

The force answers emergency calls quickly, but it needs to reduce the rate at which callers abandon non-emergency calls

Dorset Police answers 999 emergency calls quickly on most occasions. It has improved its performance from previous years, but it doesn’t yet meet the national target of answering 90 percent of 999 calls within 10 seconds. Staff generally answer 101 non-emergency calls promptly. They triage and assess the vulnerability of the caller. We saw that call handlers act politely, appropriately and ethically, always using clear, unambiguous language. But when calls aren’t immediately resolved, staff place them in a queue for further service. They tell these callers how to make an online report, but callers who don’t do this may abandon their call rather than wait.

The national standard of acceptable abandonment for a force with a switchboard is 5 percent. The force exceeds this. It is working to address this problem and the abandonment rate is improving. This will give the public greater reassurance that the force is meeting its needs.

Staff assess victims’ vulnerability during initial calls, but this assessment could be more thorough

Call takers don’t always correctly identify vulnerability at the first point of contact. When a victim contacts the police, it is important all information is properly recorded and assessed, taking into consideration threat, harm, risk and vulnerability. We found evidence of staff completing a THRIVE risk assessment on almost all occasions. But they should make a more thorough and meaningful assessment of the caller’s vulnerability to make sure the force responds appropriately and provides the right services.

High staff turnover, absences and vacancies created during the pandemic may have affected how well the force can accurately assess and manage the needs of vulnerable people. The force has now given training to all control room staff, encouraging them to better understand and respond to threats.

Officers respond appropriately when they attend to victims and crime scenes

The force has invested extensively in vulnerability and domestic abuse training for its frontline officers and staff. Officers we spoke to were confident they could identify at initial attendance indicators of vulnerability, hidden harm and risk. They have been encouraged through their training to be professionally curious. They complete in‑person risk assessments for domestic abuse victims and others in the household. We were pleased to find officers use their powers effectively to protect children. And they complete at the right time reports that assess a person’s vulnerability and need for continuing support. Officers have a good understanding of their duty to immediately safeguard vulnerable people.

It is important that officers gather evidence promptly. Action they take in the period immediately after the report of a crime may minimise the amount of evidence that is lost to an investigation. This is sometimes referred to as the golden hour. Officers understand the importance of immediate evidence-gathering and supervisors are confident they can provide adequate guidance and support. Response officers we spoke to reiterated this, describing supportive and knowledgeable supervisors. This is positive as it gives reassurance that those who first attend incidents are likely to act appropriately. It also shows the most vulnerable are likely to be protected and referred to the right organisations for support. But the delays in attendance that we have identified will affect the quality of service victims receive.

The force works effectively with mental health providers, who told us that officers respond well to those in need of help. Staff have access to round-the-clock advice from mental health professionals. At peak demand times, mental health specialists join officers on patrol to respond more effectively. Officers can use ‘retreats’ and community ‘front rooms’, staffed by mental health professionals and peer specialists, for those reaching crisis point. This joint approach is positive. It gives vulnerable members of the public appropriate care and it lets officers deal with other complex demands and spend less time in hospital.

The force understands its demand and how to prioritise, but it can’t always resource this effectively

The force has a good understanding of its demand. It uses modelling software that has previously been accurate and it prioritises the most significant threats at weekly tasking meetings. Management meetings take place three times in each 24-hour period. Those attending management meetings review new information about threat, harm and risk, correctly allocating police resources. We also found that crimes are investigated by officers with the right level of training on almost all occasions.

But the force doesn’t consistently understand what resources it has available or where they are. This contributed to delays in responding to the public during the summer of 2021. Improved understanding of new IT systems is helping to give the force a more detailed picture so it can address these gaps.

The force is agile and can move resources to support additional demand when it needs to. But it relies too much on overtime, both in the control room and in response teams to manage calls for service. Members of the workforce recognise that a combination of factors over the summer of 2021 has increased the force’s expectations of them. But they will be less willing to continue working in this way in the long term. The force plans to address this by introducing a more effective appointment system for victims and maximising the capacity of its desk-based incident resolution centre.

A strategic demand group has made sure modelling of predicted demand for 2022 has included contingencies taking account of the higher number of 999 calls the force experienced over a longer period than usual in 2021.

Understanding and addressing this increased demand means the force will improve services for victims and maintain the positive attitudes and wellbeing of its workforce.

Percentage change in 999 calls received each month from April to November 2021 compared to the same month in 2020

Source: Dorset Police data

The force understands and addresses the wellbeing needs of contact management staff

The force has a comprehensive wellbeing programme for its workforce. It also has a bespoke plan for contact management staff. Despite the demands of the role, we found staff are positive and feel well supported by approachable supervisors and leaders. The force has invested heavily in improving the working environment for contact management staff. This includes providing trauma support, breakout spaces, and learning and development opportunities. Staff and supervisors understand how to use reasonable adjustments and flexible working policies.

Exit interviews are completed and reviewed. This is important as the contact management command has suffered from higher than usual attrition rates over this inspection period. Some staff returned to furloughed roles and others left citing the demands, responsibility and remuneration of the role as reasons for leaving. As part of its response, the force has introduced a satellite site in Bournemouth, where it has been easier to attract staff. In addition, an estates improvement plan will be implemented in 2022. Enhancing the working environment and using space in Bournemouth, with staff recruited from a more densely populated area, may help the force retain staff and improve services to the public.

Requires improvement

Investigating crime

Dorset Police requires improvement at investigating crime.

Proportion of offences recorded in Dorset with outcomes where action was taken and of offences recorded in Dorset with an outcome of ‘evidential difficulties: suspect identified; victim does not support further action’ (outcome 16). Offences were recorded in the year ending 30 June 2019 to the year ending 31 March 2021

Note: Action taken outcomes include: charge/summonsed, cautions (adult and child), taken into consideration, penalty notices for disorder, cannabis/khat warnings, community resolutions, and action undertaken by another body/agency

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force investigates crime.

The force has strengthened strategic and operational governance arrangements to improve investigative performance

The force has developed the way it governs investigative performance, which is starting to lead to improved results for victims. Neighbourhood policing teams in Dorset are split into two local policing areas, aligned to the county’s two councils (Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole (BCP) and Dorset County). A new operating model means that both areas have regular performance and standards boards that inform a force-level performance board. A continuous improvement board complements this approach by identifying themes to help improve and maintain standards.

A Make the Difference team is responsible for internal audits and thematic reviews to make sure the force takes all opportunities to improve. A force audit found the need to improve supervision and victim care. This was similar to our inspection findings. The force is now applying more rigour, with an improvement plan to help it comprehensively understand all investigative performance.

The force understands the investigative demand it faces and the resources it needs to meet that demand effectively, including addressing the shortage of investigators

Dorset Police uses demand modelling software and the force has completed shift pattern reviews and activity analysis. It has recently analysed investigative officer workloads and the time it takes to progress investigations. A comprehensive workforce dashboard shows officer workloads by policing command and location. But the force can’t always match demand in some areas. This is due to shortages of investigators who are specially trained in investigating serious and complex crime. This affects the ability of investigators and supervisors to conduct timely and high‑quality investigations.

The force is addressing the shortage of detectives (which continues to be a national problem) with an investigative resilience action plan. This promotes diverse entry routes, such as the Detective Degree Holder Entry Programme, and the force attracts transferees from other areas. The force offers investigators bonus payments and there is additional support for those wishing to join and become accredited.

Changes in national guidance to prevent miscarriages of justice have put more demands on investigators when preparing court case files. The force is now using more staff to support this preparation. Despite these challenges, Dorset Police continues to allocate investigations to those with the right skills and training. It does so using effective processes based on an assessment of complexity, threat, risk and harm. Increasing the number of investigators will mean this will continue to be the case.

There have been improvements to forensic and digital examination services

Additional funding for equipment, resources and training has reduced backlogs. Staff examine high-harm cases and victims’ phones promptly. But while provision for lower-risk cases is improving, it can still be slow and outside agreed service levels. This is an area of constant growth in policing as the capacity for devices to store data increases. The force collaborates with three other forces (through South West Forensics) to drive efficiencies and new processes. And it uses an effective triage function to prioritise examinations. It has increased mobile examination hardware and uses trained crime scene investigators.

Dorset Police is one of the first forces nationally to use recent technology allowing them to send fingerprints directly from crime scenes and suspects to teams who immediately analyse them. This continuous exploration of new ways of working will improve efficiency, reduce the time taken for examinations and help investigations progress faster.

There is an emphasis on protecting and supporting victims who are unwilling to engage in the criminal justice process

As previously explained in this report, the number of victims not wishing to support prosecutions has been growing in Dorset. The time the force takes to complete an investigation may be a factor. Other factors that may contribute include delays to court processes because of previous COVID-19 restrictions, high caseloads, and backlogs in examining devices. So it is important that the force explores all opportunities to prosecute cases and to protect victims when they don’t wish to provide evidence or go to court.

Our victim service assessment identified some cases where the force should have taken opportunities to apply for domestic violence protection orders (DVPOs). But we were encouraged to find the force has a clear focus on protecting vulnerable victims. There has been significant training for tackling domestic abuse and vulnerability. The Make the Difference team gives guidance and shares information about the best ways of working and the force has introduced domestic abuse scrutiny panels. We found some examples where successful prosecutions had taken place without the victim’s evidence. The proportion of reports of domestic abuse resulting in arrest has fallen since our last inspection – which the force must monitor carefully – but those that took place were generally prompt.

Officers make good use of body-worn video to gather evidence of offending and they consider onward safeguarding. When we spoke to investigators (including some who had transferred from other forces), they were impressed with the emphasis force leaders place on this approach. It is positive that the force is developing this culture to protect victims – and, where possible, to prosecute those offenders who rely on their victims’ silence.

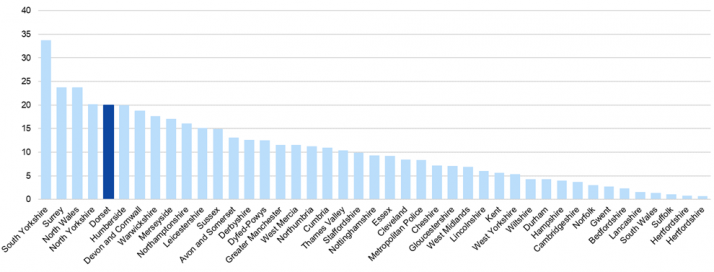

Number of DVPOs applied for per 1,000 crimes related to domestic abuse, recorded in the year ending 31 March 2021

The force responds to investigators’ wellbeing needs with comprehensive services and supportive supervision

Forces should recognise that the wellbeing of investigators, who manage high workloads, is important. Each force should make sure its staff receive sufficient support.

Dorset Police has made efforts to do this and has implemented a comprehensive wellbeing plan. This offers all staff a range of activities and support services. But we found some investigators feel unable to access these services due to the volume and nature of their work. The force has tried to address this by reducing workloads through investigative support and streamlining some of its processes. For example, it has enabled:

- direct downloading of local authority CCTV;

- better systems for uploading images to criminal justice partners; and

- using agency staff where appropriate.

For those who investigate high-harm offences, counselling is available and there is mandatory psychological screening. Supervisors know how to support investigators. And investigators report that their needs are generally met. Giving this support means that investigators are more likely to stay in their role and others will be encouraged to develop an investigative career.

Requires improvement

Protecting vulnerable people

Dorset Police is adequate at protecting vulnerable people.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force protects vulnerable people.

The force is committed to understanding the needs of vulnerable people and to protecting them

The force has a clear commitment to protecting vulnerable people. This is clear from the strategic assessments and plans it puts in place, which senior leaders oversee. Progress is monitored at force-level meetings. A project team has worked on implementing national best practice, which is aligned to the National Policing Vulnerability Knowledge and Practice Programme (VKPP). The team has received praise for its work and the way it has shared it with other organisations.

The force has made progress against the National Vulnerability Action Plan. It is also implementing plans that consider violence against women and children. It has developed its understanding of vulnerability by:

- improving identification at the point of contact;

- information-sharing with health services; and

- piloting an externally developed intelligence-led service that can better identify those at risk.

It has added to this positive approach recently by using multi-agency data to assess hidden harm, including so-called honour-based violence, forced marriage and female genital mutilation.

The force looks for ways to continually improve its services

Where areas for improvement are identified, the force responds appropriately. External experts have reviewed the force’s approach to dealing with missing children. Since then, a child protection inspection that identified areas for improvement has resulted in the force creating dedicated missing children’s teams. This is important as a recent learning event arranged by the force, with allied organisations and HMICFRS, showed the force’s initial response to missing children is still not as effective as it needs to be.

The force collates victim feedback from a range of sources, including victims of hate crime and domestic abuse, and from a Teenagers at Risk conference. Scrutiny of the effectiveness of the force’s approach to vulnerability is encouraging. This includes child and domestic abuse scrutiny panels, steering groups with other organisations, and internal reviews. These processes help to improve the service from the police and other organisations, who are working to keep vulnerable people safe.

The force gives safeguarding and support to vulnerable people, but there are sometimes delays in responding to their needs

Officers in Dorset understand the needs of vulnerable victims and there is a whole-force approach to safeguarding. Officers complete referral notices for vulnerable people, as well as specific domestic abuse referrals, which also consider the needs of any children in a household. These referrals inform organisations such as health and social services, who give further support.

Dedicated teams within the force tackle drug-related crimes and sexual exploitation of children. The force has developed the way it shares information about vulnerable children with schools (Operation Encompass). And a safer schools team identifies and addresses risks presented to and by children. The force takes part in multi-agency meetings to consider how best to support victims and in early intervention projects help divert young people from offending and criminalisation. Extensive training encourages officers to be professionally curious and to recognise and respond to signs of vulnerability.

The force is increasingly using powers designed to protect vulnerable people and victims. It uses bail appropriately. It also regularly uses protective measures such as domestic violence protection orders (DVPOs) and the domestic violence disclosure scheme (DVDS), with monitoring and enforcement action taking place. This shows the force’s commitment to keeping people safe. It also gives reassurance to vulnerable people.

But delays in responding to calls in the control room and insufficient review of risk, mean that the force isn’t meeting the initial needs of some repeat and vulnerable victims. As a result, victims may come to further harm and they may not promptly receive the services they are entitled to.

The force works effectively with other organisations to keep vulnerable people safe

The force contributes to the effectiveness of multi-agency arrangements. At both strategic and practitioner level, professional relationships enhance multi-agency working with other organisations. Multi-agency tasking processes help the force and those it works with manage those who cause the most harm. We found evidence of good attendance by partners and police at strategy meetings, with some evidence of good collaboration. Police attendees have recently received training, with the help of other groups and organisations, which will build on this collaboration. This will help make sure the safeguarding of children is effective and timely.

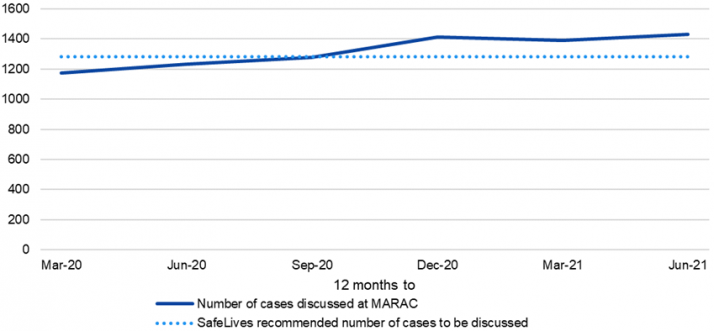

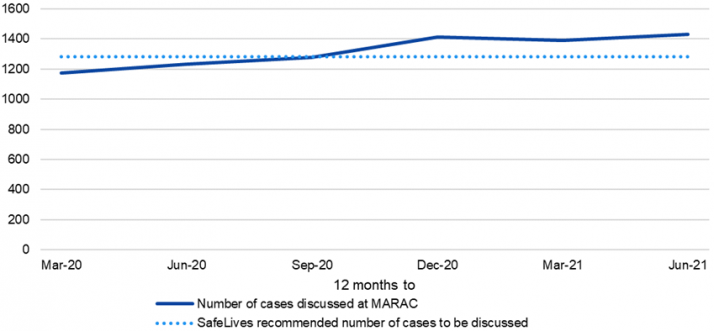

Multi-agency risk assessment conferences (MARACs) take place regularly for high‑risk victims of domestic abuse. Appropriate referrals take place and actions to protect victims are progressed. The force can influence activity at MARACs and bring about improvement through steering groups. The force collates and presents data on reductions in repeat victimisation and it uses a questionnaire to understand if victims feel safer as a result of these conferences. While the approaches in the two local authority areas are different, the force has considered the benefits of each to establish which may more effectively support victims. Working closely with other organisations to make improvements will better protect vulnerable people.

Number of cases discussed at MARAC meetings in Dorset between the year ending 31 March 2020 and the year ending 30 June 2021, compared to the SafeLives recommended number of cases

Note: Recommended number of cases to discuss is based on the SafeLives recommendation of 40 cases per 10,000 women

The force has improved its understanding of demand and resources, including when working with other organisations

The force understands its investigative workloads for those who deal with cases involving vulnerable people. It uses staff with the right training for these roles, but workloads were reported to be high. The force hasn’t always been able to effectively manage the volume of vulnerability referrals to other organisations. A small team risk assesses these referrals before they are sent to an appropriate agency such as social services. That agency can then use that information and consider any further safeguarding action.

The number of referrals reduced during COVID-19 lockdowns, but as restrictions lifted the volume increased significantly. It reached a level that meant the force couldn’t always act in a timely way. When we visited in August 2021, referrals were the highest level the force had experienced. This problem was made worse by system and user errors. This meant some incidents that should have been submitted to the multi-agency safeguarding hub (MASH) were not. The force has since developed a software system that has rectified this problem. But it also makes sure it better identifies risks and that processes are more efficient. It has supplemented this with improved guidance, training and additional resources.

The force now identifies any further surges in demand through daily automated assessment of volume. And it addressed any surges through force tasking processes. This means it can refer vulnerable victims promptly and be more likely to meet their needs. A revisit to the force in November 2021 identified that there were no backlogs. The technology used to make these improvements has been shared nationally and several forces are adopting or considering it.

The force maintains and improves the wellbeing of staff involved in protecting vulnerable people and it understands how their roles may affect them

Some staff in roles that involve investigating vulnerability report feeling stretched. But they can access psychological screening and a well-developed wellbeing plan. Regular staff surveys take account of these roles when collating responses. Counselling and regular one-to-one supervision meetings take place. The force also has a workplace policy that aims to help staff who may be experiencing domestic abuse.

In 2021, in conjunction with a university study, the force considered the way ‘moral injury’ fatigue affects staff members’ ability to maintain high standards and empathy for victims and witnesses. The force’s approach to better understand officer behaviours and share this widely has been welcomed by the VKPP, which has acknowledged the value of this information and the benefits for the police service. Making the workforce feel valued, while improving and sharing the force’s understanding of what may affect performance, are positive practices.

Adequate

Managing offenders and suspects

Dorset Police is adequate at managing offenders and suspects.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force manages offenders and suspects.

The force effectively pursues outstanding suspects and wanted persons to protect the public from harm

The force prioritises and monitors outstanding suspects. Strategic oversight and internal reviews mean leaders and supervisors stay informed. The force holds them responsible for making sure their officers know who those suspects are and that they take action against them.

A fugitive management team focuses on high-harm offenders, giving an enhanced service to help officers identify and find these offenders. Suspects the force considers to be high priority are discussed at daily force management meetings, where leaders identify the extra resources that they will need to find those suspects. We found officers were well informed about outstanding suspects. They can self-brief through an electronic daily briefing tool and by accessing the force intelligence portal for wanted persons.

Our victims service assessment and a child protection inspection identified that the force is arresting suspects promptly. Our workplace testing identified that there is an emphasis on early and continued action, with well-understood processes to circulate and pursue suspects on the national database. These investigations remain open while the force is still seeking a suspect. This proactive approach reduces the risk of further offending. Victims are kept safe and the force can progress investigations.

The force uses bail effectively to manage offenders and reduce the risks to victims

Changes to bail legislation in 2017 initially resulted in unintended consequences, with an increase in suspects who would previously have been released with bail conditions instead being released under investigation. The effect of this was that cases took longer to investigate and victims didn’t feel they were given any protection.

Dorset Police uses pre-charge bail appropriately and the force complies with national guidance. Bail conditions are subject to regular review by senior officers and magistrates. Investigators told us senior officers are supportive of the processes and ensure that they are put in place correctly. Understanding and compliance have been reinforced by:

- officers with additional training sharing their knowledge;

- leadership oversight; and

- monitoring by a review team.

The force has developed its approach to managing sexual and violent offenders and is now doing this effectively

In March 2021 it became clear that the force needed to make several improvements to the way its management of sexual and violent offenders (MOSOVO) team operated. The force should be commended for its immediate response. A strategic oversight group implemented recommendations and our subsequent review found that the force had made many improvements. It is using appropriate risk assessment tools with prompt completion and review. Officer workloads align with nationally recommended numbers and the force manages offenders to national standards. Offender managers receive appropriate training and resources to do their job. Acting swiftly in response to concerns has meant the force is better positioned to determine threats, protect the public and reduce reoffending.

Making sure offender managers are based in the right parts of the county allows them to visit offenders more efficiently. It also improves information-sharing with local officers. Those officers we spoke to showed a good awareness of sexual offenders in their areas and could immediately access information through a mapping tool. This tool highlights offenders subject to court orders that impose restrictions and conditions to prevent further offending. This is positive as it indicates if offenders are close to areas where they pose a threat. This influences patrol plans, intelligence submissions and the force’s response to breaches of orders.

The force uses preventative orders in all cases and joint consideration by different teams will further enhance this

The police online investigation team (POLIT) and MOSOVO team apply for civil and preventative orders in all cases. The force is applying computer monitoring with new software as part of these orders, which are facilitated by specialist lawyers and a range of staff. The force monitors all breaches of orders, as well as managing them effectively and taking action. It could further improve this approach by more formal liaison between POLIT and the MOSOVO team. This would help improve the quality of applications, ensuring tailored orders are considered. We encourage the force to have a structured pre-application process.

An integrated offender management (IOM) team deals with appropriate types of offenders and works in a variety of ways to reduce reoffending

The force has an IOM programme that aligns its practices to new national guidance. There is effective strategic governance with allied organisations and staff receive the right training (often with these organisations). The IOM team manages appropriate types of offenders. These include those presenting the greatest threats, such as perpetrators of domestic abuse, burglary and robbery. And it prioritises repeat offenders. We saw evidence of staff communicating and acting on threats and gathering and sharing intelligence with frontline officers.

The force uses tailored plans that consider diversions and ways of supporting offenders to reduce their likelihood of committing further crimes. The team uses statutory and voluntary flagging schemes and is trialling a domestic violence proximity notification system. This system alerts the police and the offender’s previous victim if the offender goes within a certain radius of that person.

The force uses early intervention and perpetrator programmes to reduce reoffending, but it needs to better understand the benefits and outcomes

We found good examples of evidence-based multi-agency early intervention and perpetrator programmes through the force’s productive arrangements with other organisations. For example, a diversionary intervention scheme called Footprints helps vulnerable women stay out of court. These women may have been subject to controlling relationships or they may be suffering with their mental health. This work was specially commended at the Howard League for Penal Reform community awards.

The force also focuses on domestic abuse perpetrator programmes, which are overseen by a domestic abuse perpetrator panel. These initiatives tackle the root causes of offending and encourage high-harm serial abusers to work with other organisations to reduce reoffending. The force told us an independent review found an 82 percent reduction in physical offending and a 65 percent reduction in overall offending by those who had fully engaged in the programme. This kind of evaluation is positive and the force should develop it more widely. Understanding the costs and benefits of effectively managing offenders can help assess the value of interventions and inform how the force allocates resources in future.

Adequate

Disrupting serious organised crime

We now inspect serious and organised crime (SOC) on a regional basis, rather than inspecting each force individually in this area. This is so we can be more effective and efficient in how we inspect the whole SOC system, as set out in HM Government’s SOC strategy.

SOC is tackled by each force working with regional organised crime units (ROCUs). These units lead the regional response to SOC by providing access to specialist resources and assets to disrupt organised crime groups (OCGs) that pose the highest harm.

Through our new inspections we seek to understand how well forces and ROCUs work in partnership. As a result, we now inspect ROCUs and their forces together and report on regional performance. Forces and ROCUs are now graded and reported on in regional SOC reports.

Our SOC inspection of Dorset Police hasn’t yet been completed. We will update our website with our findings (including the force’s grade) and a link to the regional report once the inspection is complete.

Building, supporting and protecting the workforce

Dorset Police is good at building and developing its workforce.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force builds and develops its workforce.

The force has an ethical culture and leaders promote an environment where officers and staff understand what is expected of them

The police Code of Ethics is well accepted. During our visits, we saw evidence of communications that reinforce standards of behaviour, including internal and external communication of misconduct cases. Proactive campaigns highlight the importance of reporting matters to the Professional Standards Department and the ways of doing so. Chief officers and senior leaders promote ethical standards. Examples of this include:

- presentations from the Professional Standards Department at training events;

- a ‘bystander’ programme that supports the workforce to challenge inappropriate behaviours; and

- promoting standards at leadership events such as the Aspire programme.

Members of the workforce were well informed about the type of inappropriate behaviours that had been reported on both nationally and locally. They felt confident to raise concerns. The force reviews cases to make sure it takes preventative and supportive action in response to any lessons learned. This is meaningful as it shows that leaders are reflective, committed to improvement and that they promote a learning culture, not a blame culture.

The force promotes an inclusive culture so that all people in the organisation feel included

Most people we spoke to (including volunteers) feel the force is an inclusive and good place to work. The force’s ethics committee has an independent chair (who also sits on chief officer selection panels) and senior leadership representation. The ethics committee considers dilemmas and shares outcomes and learning with the workforce. The deputy chief constable reinvigorated the committee in early 2021. Since then, we have seen a growing understanding of how it can help raise awareness of dilemmas the workforce encounters.

The force promotes the use of support networks, including:

- for BAME people;

- for LGBTQ+ people;

- for people who have disabilities, mental health conditions or dyslexia;

- the Women Inspire Network; and

- a men’s health forum.

Recent initiatives, such as inclusion passports, make managers aware of less obvious disabilities and adjustment needs, and an Altogether Better campaign raises awareness of workforce diversity in both Dorset and Devon and Cornwall. These initiatives encourage the workforce to submit details about protected characteristics. This isn’t a mandatory requirement, but it gives the force a better profile of its workforce. This helps it understand if it is treating all people fairly and shows its commitment to inclusivity.

The force understands the wellbeing of its officers and staff and it uses this information to develop effective plans for improving workforce wellbeing

The force has a well-informed understanding of the workforce’s wellbeing. It achieves this through a comprehensive wellbeing plan overseen by a chief officer and supportive leaders. These leaders know their workforce and how to access support for them. Staff surveys and regular feedback from staff associations and support groups inform effective strategic meetings. Workforce and wellbeing dashboards can draw on a diverse range of data, including:

- resourcing in different departments;

- progress with recruitment streams;

- types and lengths of sickness absence;

- gender; and

- protected characteristic representation.

This helps the force understand any risks to the wellbeing of its workforce and to expose any workplace disparities. The information is accessible to operational groups that the force has set up to address these issues. This will promote a resilient and valued workforce and encourage others to join.

There is a good range of preventative and supportive measures in place to improve wellbeing

The staff we spoke to knew about workforce wellbeing arrangements and how to access them. A dedicated wellbeing site on the force intranet gives guidance and signposts activities that will help officers and staff improve and maintain their wellbeing. We found creative approaches, including online cafés, surf therapy, parenting workshops, fitness trackers and a therapy dog. The force aligns its approach to the National Police Wellbeing Programme, actively promoting ways of maintaining wellbeing.

The force encourages teams to have wellbeing groups in their own departments and more formal provision is available through an employee assistance programme. Occupational health support makes sure officers and staff receive the right referrals and that measures such as counselling, physiotherapy or mental health resilience support are in place.

Despite a challenging year, the force is maintaining the wellbeing of its workforce through supportive leadership and interventions

Leaders are committed to improving the wellbeing of their workforce. Heightened summer demand and increased abstractions have created additional pressures. The force needs to more consistently anticipate and respond to any future peaks. But it is clear leaders have worked hard to support their staff. For example, the force has developed comprehensive plans to manage investigative, vulnerability and control room demands for services. This is because the force recognises that wellbeing measures alone aren’t always enough when there are high workloads.

Senior leaders are approachable. They take part in question and answer sessions and representatives from staff associations can reach them easily. We found that the force can make changes when members of the workforce raise concerns. Examples of this include:

- reviewing custody officers’ shift patterns;

- ensuring there is protected learning time;

- overlapping shift patterns to improve resilience; and

- better considering roles for those on recuperative duties and with flexible working arrangements.

Supervisors are also aware of their wellbeing responsibilities. They have received training in recognising signs of poor health and they understand their role in supporting their staff. We found officers and staff have regular contact with their supervisors. This contact time is used to consider ways to manage high workloads and to make sure staff access relevant wellbeing support. For those in high-risk roles, this includes regular mandatory health screening and access to counselling. A trauma risk management (TRiM) process is available to anyone exposed to serious incidents that may affect their health.

By addressing the challenges members of the workforce face, leaders show a commitment to improving wellbeing. This means officers and staff feel listened to. They are confident enough to voice concerns and support the force’s goals.

The force understands its recruitment needs

The strategic alliance between Dorset Police and Devon and Cornwall Police has a well-developed people strategy. This includes a five-year recruitment schedule with progress monitored through the Strategic People’s Board. The board considers matters such as recruitment, promotion, talent management, workforce representation and retention.

A workforce capability dashboard provides an up-to-date overview and helps to recognise threats. This is important as the workforce has been stretched in some departments. To alleviate this, the force has maximised opportunities to recruit staff through the national uplift programme. It encourages recruitment through many pathways, in particular through direct entry schemes (assessed by the College of Policing as meeting national standards) and by making progress with plans to increase the number of detectives and contact management staff.

The recruitment plan incorporates actions to improve diversity in policing. The force has introduced a candidate tracking system. This will help it better understand why some candidates from BAME communities withdraw from the recruitment process. The force speaks to candidates who leave or stop their application so it can understand and address the reasons. A positive action support programme is available to potential recruits and those seeking promotion. And the work of the positive action team underpins this approach. This team is overseen by a positive action leadership group and force representation at the national Positive Action Practitioners’ Alliance.

The chief constable has single overview of the force’s equality, diversity and inclusion plan. This should help the force improve its understanding of the factors that influence recruitment and retention. This is positive as there has previously been a somewhat disparate approach. The force needs continued focus so that it can build on this partial progress and make sure the workforce can better reflect its communities.

The force has invested in significant training for its workforce, but it can strengthen the link between appraisals and development

Throughout all the departments we inspected, we found that the force provides training that is relevant to the roles and helps to professionalise them. A workforce planning framework with a learning and delivery plan is in place. The force develops leaders through a framework that considers talent management, external leadership training and leadership skills audits. Leaders consider wider professional development, including succession planning, at a training planning board. Leaders and supervisors complete one-to-one meetings with staff.

But the force could take more opportunities to understand and act on learning and development needs during annual professional development reviews (PDRs). Some members of the workforce we spoke to felt the reviews had limited value. This – combined with deficiencies identified with a new digital PDR system, which the force has now rejected – has led to the force losing some momentum. It is having to reassert the importance of this link between performance and development.

Good

Strategic planning, organisational management and value for money

Dorset Police is adequate at operating efficiently.

Main findings

In this section we set out our main findings that relate to how well the force operates efficiently.

The force has an effective strategic planning framework, making sure it tackles what is important locally and nationally, and it engages well with communities to understand their needs

The force works constructively with the police and crime commissioner (PCC) to align its activities to the priorities in the Police and Crime Plan. As well as the intelligence it gets from the PCC’s community consultation, the force gains a good understanding of communities’ needs and expectations through strategic meetings with local organisations and force-led quarterly surveys. It makes good use of social media, such as Facebook Live events, to engage with the public. There is also a youth parliament and the force has commissioned special focus groups to understand community needs.

There is a clear governance structure, so leaders can oversee and scrutinise all force performance well. Neighbourhood teams work well in their communities. Dedicated engagement officers find the opportunities and work alongside police community support officers and other neighbourhood police officers. New enforcement teams have further strengthened the neighbourhood teams, giving the extra capacity that was needed.

The force has a good understanding of the capabilities of its workforce

Where the force has identified skills and capacity gaps, it has put plans in place to address them. It doesn’t always have enough resources to meet peak demands, but it does move extra staff into areas when they are needed. The force continues to prioritise neighbourhood policing and protecting vulnerable people. It is putting extra resources into its neighbourhood teams to allow greater focus on preventing crime and anti-social behaviour. It has done the same for teams that investigate high-harm offenders and for those that work with other organisations to make sure vulnerable victims get the support they need.

It has planned well for how best to recruit, train and use the extra police officers funded by the Government’s police uplift programme. The extra funding available to the force is helping it increase its police officer strength by 15 percent. There is a detailed recruitment plan through to 2025/26, which uses a variety of entry programmes and training schemes. The force has also made robust plans to tackle its shortage of trained detectives, including the degree holder entry programme and other entry routes. It is already starting to see an increase in detective numbers. Senior leaders are closely monitoring where staff are based and the numbers of investigations they are managing throughout all areas of the force’s operation.

The force makes best use of available finances and its plans are both ambitious and lasting

The force’s financial planning and management systems are sound. They are led at the highest level through the Dorset Resource Control Board, which the PCC and the chief constable jointly chair. The board allocates resources according to the priorities in the Police and Crime Plan. This is informed by the understanding of demand coming from the force management statement. The force has outlined in the statement where it will make additional investment to keep pace with the demand.

The financial and workforce plans have a clear focus on improving efficiency. The force has a track record of achieving efficiency savings. It has identified £1m of additional savings in 2021/22. Most of these savings were from non-staff costs. It compares its costs with other similar forces using our value for money profiles to understand any areas where its costs are higher or lower than the average. The independent audit committee routinely scrutinises this approach.

The force collaborates to improve services