Getting the balance right? An inspection of how effectively the police deal with protests

Contents

- Foreword

- Summary of findings

- How well do the police manage intelligence about protests?

- How well do the police plan and prepare their response to protests?

- How well do the police collaborate in relation to protests?

- How effective are decision-making processes and how do they affect the police response to protests?

- Does the current legislation give the police the powers they need to deal effectively with protests?

- 1. About the inspection

- 2. Police intelligence about protests

- The importance of gathering intelligence on aggravated activists

- How effective are national arrangements for managing protest‑related intelligence?

- How effectively do police assess protest-related risks using intelligence?

- How effectively do police manage intelligence on aggravated activists?

- How effective are intelligence arrangements at force level?

- The police use of covert sensitive intelligence-gathering methods

- 3. The police’s planning and preparation for their response to protests

- How effective are the planning and preparation processes at local, force, regional and national levels?

- How well do local, force, regional and national capacities and capabilities allow an effective response to protests?

- How well does local, force, regional and national training (including authorised professional practice and other guidance) allow an effective response to protests?

- How well do equipment and technology allow an effective response to protests at a local, force, regional and national level?

- 4. Collaboration and learning between forces and with other organisations

- How effectively do the mutual aid arrangements work?

- How effectively do forces collaborate to share resources, such as commanders and specialist capabilities?

- How effectively do forces collaborate to learn from experience?

- How effectively do forces collaborate with other organisations such as local authorities, emergency services and other public services?

- 5. Police decisions and their effect on the public

- How effectively do the police’s decision-making processes balance the competing rights and interests of protesters with those of other people?

- How effectively are commanders’ decisions communicated and understood?

- How effectively do officers understand and use their existing powers to police protests?

- How effectively do the police assess the impact of the protest and the impact of the police response on communities?

- Conclusion

- 6. Protest-related legislation

- Does the current legislation give the police the powers they need to deal effectively with protests?

- The evolution of proposals for new legislation

- Views on the five proposals

- Two recommendations to align legislation so that police have the same powers to deal with processions and assemblies

- The police service’s 19 potential proposals

- Annex A – Relevant articles in the European Convention on Human Rights

- Annex B – List of forces and other organisations

- Annex C – Definitions and interpretation

- Back to publication

Print this document

Foreword

On 21 September 2020, the Home Secretary commissioned us to conduct an inspection into how effectively the police manage protests. This followed several protests, by groups including Extinction Rebellion, Black Lives Matter and many others. Some of them had caused disruption in various parts of the country, including London and other cities. She required us to assess the extent to which the police have been using their existing powers effectively, and what steps the Government could take to ensure that the police have the right powers to respond to protests.

In recent years, increasing amounts of police time and resources have been spent dealing with protests. In April and October 2019, Extinction Rebellion brought some of London’s busiest areas to a standstill for several days. The policing operation for the two extended protests cost £37m, more than twice the annual budget of London’s violent crime taskforce.

There have also been long-running demonstrations against the badger cull, against companies involved in certain techniques used in onshore oil and gas production (namely the extraction process commonly known as ‘fracking’), and against the construction of the high-speed rail line HS2.

Protests are an important part of our vibrant and tolerant democracy. Under human rights law, we all have the right to gather and express our views. But these rights are not absolute rights. That fact raises important questions for the police and wider society to consider about how much disruption is tolerable, and how to deal with protesters who break the law. A fair balance should be struck between individual rights and the general interests of the community.

We inspected ten police forces with recent experience of policing protests and consulted a wide range of other bodies, including protest groups and – through a survey of over 2,000 people – the general public.

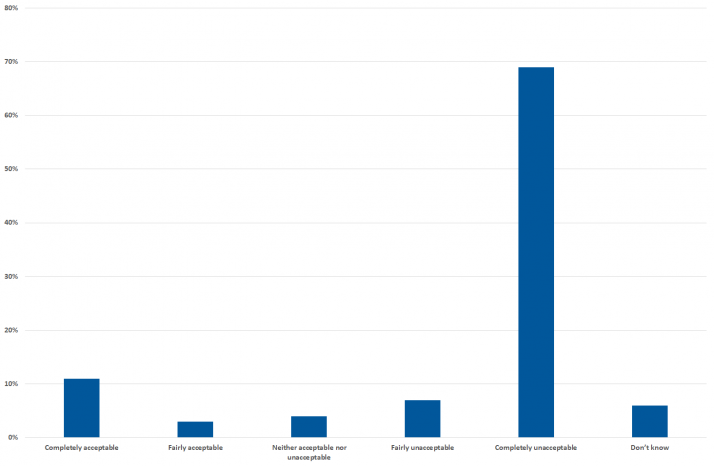

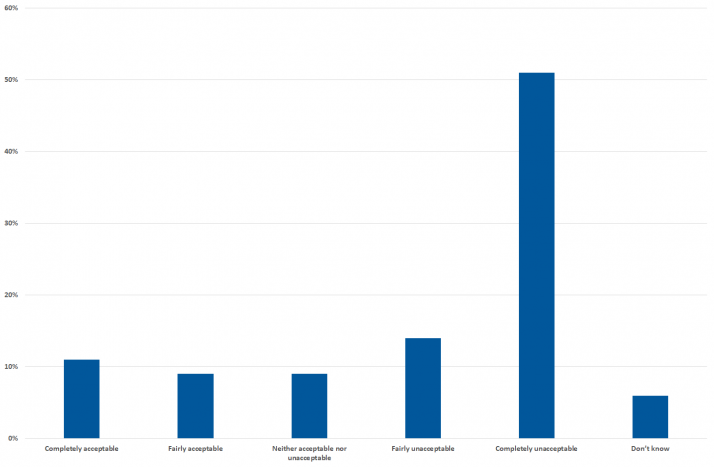

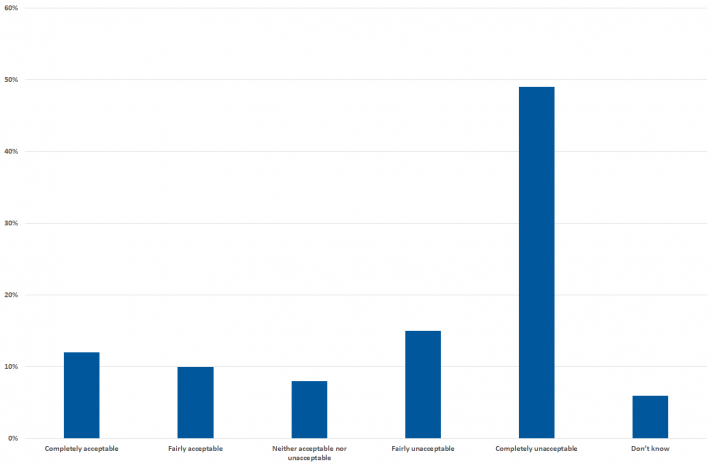

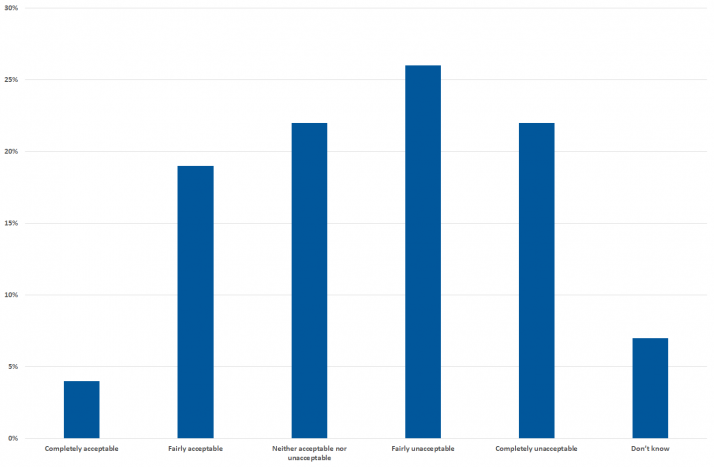

In our public survey, for every person who thought it acceptable for the police to ignore protesters committing minor offences, twice as many thought it was unacceptable. And the majority of respondents felt it was unacceptable for protests to involve violence or serious disruption to residents and business.

Among the police officers, protesters, business leaders and others we interviewed, we heard strong and often polarised views. This amply illustrated just how much of a balancing act the police face when dealing with protests, particularly those which are designed to be peaceful and non-violent, and yet can be highly disruptive.

Having reviewed the evidence, our conclusion is that the police do not strike the right balance on every occasion. The balance may tip too readily in favour of protesters when – as is often the case – the police do not accurately assess the level of disruption caused, or likely to be caused, by a protest.

These and other observations led us to conclude that a modest reset of the scales is needed. To help achieve it, our report includes four areas for improvement and 12 recommendations.

Some of our commentary is about the law concerning protests. While emphasising that legislative reform will not be a panacea for the problem of disruptive protest, we offer our qualified support for five Home Office proposals for changes in the law. And we make two recommendations for further changes in the law. These are set out in Chapter 6.

Our other recommendations and areas for improvement are designed to help the police get the balance right by:

- equipping police commanders with up to date, accessible guidance and a greater understanding of human rights law;

- ensuring that they consider the levels of disruption or disorder above which enforcement action will be considered;

- improving the way that police assess the impact of protests, to help them understand fully the impact on local residents, visitors to an area, businesses, and the critical infrastructure;

- improving the quality of police intelligence on protests, particularly intelligence about those who seek to bring about political or social change in a way that involves unlawful behaviour or criminality;

- addressing a wide variation in the number of specialist officers available for protest policing throughout England and Wales;

- supporting forces to use live facial recognition technology in a way that improves police efficiency and effectiveness, while addressing public concerns about the use of such technology;

- prompting better exchange of legal advice and other information between officers, using an established system provided by the College of Policing;

- securing more consistent, effective debrief processes;

- reconsidering police and local authority powers and practices concerning road closures during protests; and

- stimulating research into the use of fixed penalty notices for breaches of public health regulations in the course of protests; and using it to inform a decision on whether to extend the scheme to include further offences commonly committed during protests.

Looking ahead, there is every reason to expect that protest will continue to be a feature of modern life. There will remain a considerable public interest in ensuring that a fair balance is struck; the police and other bodies to which our recommendations are directed should act on them.

Her Majesty’s Inspector of Constabulary

March 2021

Summary of findings

How well do the police manage intelligence about protests?

Police use the term ‘aggravated activism’ to describe the behaviour of those who seek to bring about political or social change in a way that involves unlawful behaviour or criminality. In this report, we refer to those who behave in this way as ‘aggravated activists’.

In some respects, the police’s management of protest-related intelligence needs to improve, particularly in relation to aggravated activists.

National arrangements for managing protest-related intelligence

Until April 2020, Counter Terrorism Policing (CTP) was responsible for managing protest related intelligence at a national level. Then the National Police Coordination Centre’s Strategic Intelligence and Briefing team (NPoCC SIB) was created to take national responsibility for protest-related intelligence. This included giving intelligence assessments to forces to help them plan and prepare for policing protests.

The transfer of responsibility coincided with the first COVID-19 national lockdown, which presented serious logistical problems for the new team. Despite this, the NPoCC SIB has worked hard to improve the quality of its assessments. Its effectiveness, however, is limited by the quality of intelligence it receives from forces.

Areas for improvement

Forces should improve the quality of the protest-related intelligence they provide to the National Police Coordination Centre’s Strategic Intelligence and Briefing team. And this team should ensure that its intelligence collection process is fit for purpose.

The police rely on intelligence to assess protest-related risks. They record this using ‘public order strategic threat and risk assessments’ (POSTRAs) at force, regional and national levels.

We reviewed POSTRAs from the forces we inspected and found that only three contained intelligence relevant to protests forces had experienced during 2020. The police are making major changes to ensure that the assessment process reflects the most up-to-date intelligence.

There is a lack of national co-ordination of how the police gather intelligence on protest-related aggravated activists. This means that forces cannot be fully effective in responding to protests. The police are planning to improve in this area and, on a trial basis, are creating a new team for this purpose.

Recommendations

By 30 June 2022, the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC), through its National Public Order Public Safety Group and National Protest Working Group, should analyse the results from the national development team trial. In the light of this analysis, the NPCC should secure an appropriate longer-term arrangement for managing the risks presented by aggravated activists.

Managing protest-related intelligence at a force level

Forces’ intelligence units deal with many issues besides protest, including serious organised crime, modern slavery and child sexual exploitation. Recent protests have stretched resources in most forces, and it can be a struggle for intelligence departments to balance competing priorities.

There are strong links between the protest-related intelligence teams in forces and operational planning teams. Intelligence about protests is usually shared quickly, so that commanders can make effective decisions about how to respond.

Some forces do not make regular use of ‘forward intelligence team’ (FIT) officers because they fear that this might increase confrontation with protesters. A consequence of this can be that ‘police liaison team’ (PLT) officers, who are meant to help communication between the police and protesters, are asked to gather intelligence as well. This blurs the boundaries of the role and can erode protest groups’ trust in PLTs.

Use of covert sensitive intelligence-gathering methods

The police can use covert sensitive intelligence-gathering methods to prevent protest related crime and disorder, if they meet stringent legal requirements. The police use most of these methods, such as directed surveillance, in a limited way.

The need to develop these methods is highlighted within the latest police ‘public order public safety’ (POPS) strategic risk assessment. We agree with this assessment. It is particularly relevant if the police are to improve their focus on aggravated activists, as we have recommended.

Until September 2020, CTP was responsible for managing protest-related covert human intelligence sources (CHIS). The term CHIS refers to people who provide intelligence to the police (mostly members of the public and more commonly known as ‘police informants’).

Since September 2020, the responsibility has been devolved to forces, which operate a different model. The integration of protest-related CHIS management with the force model is still in its early stages. We have concerns about how well it will work and whether it will meet the demand.

Recommendations

With immediate effect, the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC), through its National Public Order Public Safety Group and National Protest Working Group, should closely monitor progress on integrating the management of protest-related covert human intelligence sources with the devolved force model. And, by 30 June 2022, the NPCC should ensure that a post-implementation review is conducted.

How well do the police plan and prepare their response to protests?

Police planning teams are usually skilled, experienced and effective at preparing and planning for the response to protest. Unsurprisingly, we found that the forces that regularly deal with protest tended to have the best planning practices.

Working with organisers and others

Forces work with the companies and organisations affected by protest to help plan the policing. Forces also work with protest organisers, most of whom collaborate with the police to make sure that protests are safe. This is not always the case, however.

When organisers fail to notify the police about a protest, or notify the police at a late stage, they can jeopardise the safety of those involved and reduce or remove the police’s ability to plan ahead. They also miss an opportunity to come to an agreement with the police about an acceptable level of disruption. (Courts have repeatedly emphasised that a degree of temporary interference with the rights of others is acceptable in order to uphold freedoms of expression and assembly.)

Forces and protest groups told us that PLTs play an important role in helping communication at the planning stage.

Specialist training

The police have developed a range of specialist roles in relation to protest. For example, protester removal teams (PRTs) are trained to remove protesters from lock-on devices. But we found that forces do not have a consistent way of determining the number of trained officers they need. As a result, the number of specialists available varies widely throughout England and Wales.

Areas for improvement

On a national, regional and local basis, the police should develop a stronger rationale for determining the number of commanders, specialist officers and staff needed to police protests.

Very few officers have been trained to police protests at sea. Although this type of protest is relatively rare, it is important that the police have the capacity to deal with protesters who target oil installations or seek to impede ships at sea, from fishing vessels to ocean liners and nuclear submarines.

Officers are not coming forward in sufficient numbers for training in specialist protest policing roles. Reasons for this include frequent weekend working, exposure to risky operations, and the relentless insults and abuse that they often face when dealing with protests. Interviewees told us about the additional stress caused by footage or photographs being posted on social media. Some officers fear that this might put their families at risk.

Police support unit training currently prepares officers to deal with a worst-case scenario: hostile and violent crowds. It does not equip them fully to deal with modern protests, many of which are non-violent. We were pleased to see that new refresher training was being introduced to address this.

Guidance and advice

The College of Policing’s ‘authorised professional practice’ (APP) contains 30 tactical options to deal with public disorder and protests. It is out of date: it does not include recent relevant case law, or information on certain new and emerging tactical options. The College is planning a review.

We were pleased to see that the NPCC and the College of Policing have produced a comprehensive and detailed document giving operational advice for protest policing. However, we found problems with some of its legal explanations, particularly how it sets out the police’s obligations under human rights law. We are also concerned about some aspects of the document’s commentary that we felt were open to misinterpretation, particularly by members of the public who may read the document after it is published.

We raised these points with the NPCC. As our inspection ended, the NPCC and the College of Policing were revising the document in the light of our concerns. We intend to review the revised version when it becomes available.

The NPCC used to produce a protest aide memoire for officers and we understand that its Tactics, Training and Equipment Working Group is considering whether to replace this with a digital version. This seems a good idea and there is an opportunity to co-ordinate this work with both the College of Policing’s review of the APP and the revisions to the NPCC’s operational advice document. It would be beneficial for the police to make contemporary guidance, policy and advice accessible in one place.

Recommendations

By 30 June 2022, the College of Policing, through its planned review, should bring the public order authorised professional practice (APP) up to date and make arrangements to keep it current, with more regular revisions as they become necessary. It would also be beneficial to consolidate the APP, protest operational advice and aide memoire into a single source (or a linked series of documents).

Using equipment and technology

The police make good use of equipment and technology in relation to protest. Drones have significantly improved police commanders’ ability to monitor protesters and deploy officers accordingly. We were impressed by the work of PRTs in dealing with some very complex lock-on devices used by some protest groups.

The police’s use of facial recognition technology divides opinion: opponents point to its potential to violate human rights, while supporters believe it could help the police to identify those intent on committing crime or causing significant disruption and disorder. A recent Court of Appeal judgment has helped to clarify matters, but further policy development work is needed.

Areas for improvement

The police’s use of live facial recognition technology is an area for improvement. The National Police Chiefs’ Council should continue to work with the Government and other interested parties. These bodies should develop a robust framework that supports forces, allowing the use of live facial recognition in a way that improves police efficiency and effectiveness while addressing public concerns about the use of such technology. The framework should be designed to help the police satisfy the requirements explained in the Court of Appeal judgment: [2020] EWCA Civ 1058.

How well do the police collaborate in relation to protests?

The police generally collaborate well in relation to protests. However, we found some problems both with the debriefing process and the processes forces use to learn from experience, and then to share that knowledge with other forces.

Mutual aid and collaboration between forces

Mutual aid arrangements usually work well, with resources and specialists moving across force boundaries on a regular basis to deal with protest. The police regularly test the national mobilisation of resources and determine opportunities for improvement. Forces are confident that they can meet their national obligation to supply resources and will receive help from other forces when they themselves need it.

Larger forces tend to have their own trained and equipped specialist resources. For reasons of economy, smaller forces tend to work to a collaborative agreement with neighbours or have arrangements to buy in resources from larger forces.

Forces that deal with more protests often allow commanders from other areas to visit and review protest operations or gain experience by shadowing their commanders. Some forces also allow visiting commanders to command the policing of a protest in the host force area.

The College of Policing runs a website called Knowledge Hub. This has themed groups in which practitioners from all areas of policing can ask questions and share information. Knowledge Hub isn’t used by forces in connection with protest policing as much as it is used for other types of policing. We found that forces do not do enough to share legal opinion or case law on protest policing. And officers and staff rarely use Knowledge Hub’s ‘Specialist Operational Support – Public Order Public Safety’ group.

Recommendations

- By 31 December 2021, chief constables should make sure that their legal services teams subscribe to the College of Policing Knowledge Hub’s Association of Police Lawyers group.

- By 31 December 2021, the College of Policing should ensure that all Public Order Public Safety commander and adviser students attending its licensed training are enrolled in the College of Policing Knowledge Hub’s Specialist Operational Support – Public Order Public Safety group, before they leave the training event.

Debriefing and learning from experience

Forces are not always sharing information from protest-related debriefs as effectively as they should. They are generally good at conducting internal debriefs of controversial or high-profile protests, but often do not debrief after smaller or lower profile protests. There are also weaknesses in the way that forces use less urgent information from debriefs or share such information nationally.

The College of Policing and the NPoCC have set up what should be an effective process for submitting and sharing information from debrief forms. But forces often do not comply properly with this process.

Recommendations

By 31 December 2021, chief constables should ensure that their forces have sufficiently robust governance arrangements in place to secure consistent, effective debrief processes for protest policing. Such arrangements should ensure that:

- forces give adequate consideration to debriefing all protest-related policing operations;

- the extent of any debrief is proportionate to the scale of the operation;

- a national post-event learning review form is prepared after every debrief; and

- the form is signed off by a gold commander prior to submission to the National Police Coordination Centre.

Working with other organisations

Forces usually work well with other organisations to police protest. These include local authorities, fire and rescue services, and ambulance services, as well as councillors, other public services, other police forces and community representatives.

Forces involve these parties right at the early stages of protest planning and continue working with them throughout the event. They also encourage representatives from these organisations to work alongside police gold or silver commanders during events. Local authorities often provide facilities during protest, such as road closures, barriers, water and toilets for protesters, lighting, advice and information, and access to their CCTV network.

Any concerns between the police and these other organisations are usually quickly resolved. However, there can be differences of opinion between the police and the local authority relating to their powers to close roads during protests. There is also a question about whether the legislation the police use when closing roads, which was enacted in Victorian times, meets the standards required by modern-day human rights law.

Recommendations

By 30 June 2022, on behalf of HM Government, the Home Office should lead a joint review of police and local authority powers and practices concerning road closures during protests. This should be done with the support of, and in consultation with, the Department for Transport, the Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government, Westminster City Council, the Metropolitan Police, Transport for London and other interested parties. The review should include a comparison of the arrangements in London with those in other parts of England and Wales. Its findings should lead to decisions on whether to:

- retain, modify or repeal section 52 of the Metropolitan Police Act 1839 and section 21 of the Town Police Clauses Act 1847; and

- establish new multi-agency arrangements for implementing road closures in London during protests.

How effective are decision-making processes and how do they affect the police response to protests?

The police’s approach to protests needs to strike a delicate balance between the rights of protesters and the rights of local residents, businesses, and those who hold opposing views. This is no easy task, and the police inevitably attract criticism both from those who believe they are ‘too soft’ on protesters and from those who believe they are ‘too hard’ on protesters by unacceptably restricting the right to protest.

Our evidence suggests that, when forces do not accurately assess the level of disruption caused, or likely to be caused, by a protest, the balance may tip too readily in favour of protesters. We conclude that a modest reset of the scales is needed.

Human rights legislation and case law

In making decisions about how to respond to a protest, public order commanders need to consider domestic human rights legislation. And they must also consider a patchwork of European case law. These have established precedents on issues such as how long protests can reasonably go on for, and the level of disruption that protests can reasonably cause.

Examining the gold strategies and silver plans submitted as part of our document review, we found that commanders generally showed a grasp of human rights legislation. However, we did not see evidence that they consistently considered the wider legal picture.

For example, the European Court of Human Rights has ruled that, when protesters deliberately set out to cause disruption, the police have a “wider margin of appreciation”. This means that the police can – and in our view should – take protesters’ intentions into account when deciding whether it is proportionate to restrict a protest.

Recommendations

By 30 June 2022, the National Police Chiefs’ Council, working with the College of Policing, should provide additional support to gold commanders to improve the quality of gold strategies for protest policing. This support should include:

- the creation and operation of a quality assurance process; and/or

- the provision of more focused continuous professional development.

The additional support should ensure that gold commanders for protest operations include an appropriate level of detail within their gold strategies. This may include the levels of disruption or disorder above which enforcement action will be considered.

Our public survey

YouGov conducted a survey on our behalf to gauge the public’s perception of the policing of protests. Between 27 and 29 November 2020, it surveyed 2,033 adults in England and Wales (on a sample of this size, random sampling error is up to 2 percent).

The majority of respondents felt it was unacceptable for protests to involve violence or serious disruption to residents and businesses. But their views were more divided when protest caused only minor inconvenience to people locally. The survey showed less support for police use of force when protesters were not violent.

Briefing and communicating

Forces usually have good protest-related briefing processes and commanders’ decisions generally reach the front line effectively. However, gold strategies often do not set out the limits of acceptable behaviour from the protesters. Better explanations of these limits would help officers to understand what is expected of them and empower them to take appropriate action.

Non-specialist officers receive limited training in protest policing. As a result, they often lack confidence in using police powers. Some officers are anxious about attracting complaints and being filmed in protest situations. It is important that forces provide good-quality training and briefing before deploying officers into these situations.

Assessing the impact of protests

Forces should make better use of community impact assessments to evaluate the impact of protests on those who live in, work in or visit an area. The process should include regular reviews and updates, so the police can respond to changing circumstances. Only seven of the ten forces we inspected submitted any community impact assessments for examination, and some of those we examined were of a poor standard.

None of the debrief documentation we reviewed showed that forces had considered the degree of disruption experienced by people not involved in a protest. Some interviewees from businesses also told us that the police did not take enough account of the financial impact of protest. Our conclusion is that forces are not doing enough to assess and document the impact of protests.

Areas for improvement

The police’s protest-related community impact assessments are an area for improvement, particularly those that need to be completed after the event. These assessments should assist the police to understand fully the impact of protests on communities. They should include assessments of the impact of protest on local residents, visitors to an area, businesses, and the critical infrastructure including transport networks and hospitals.

Recommendations

By 30 June 2022, the National Police Coordination Centre should revise the national post-event learning review form so that it contains a section to report on the policing operation’s impact on the community.

Public transport providers can help a force to make more informed decisions about how to police a protest. But, in some forces, we did not see appreciable evidence of continuing work with them during the protest. The Metropolitan Police routinely includes Transport for London in its strategic planning group, and they maintain communication throughout protests. In forces where similar co-operation doesn’t routinely occur, we would encourage them to work more closely with public transport providers.

We have seen many examples of forces responding effectively to the challenge of policing protests, but some notable concerns remain. Although not evident in every force, generally the main ones to be addressed are:

- a limited appreciation of the full impact of protest on other people’s daily lives;

- an insufficiently wide knowledge of human rights law and relevant case law;

- a need for commanders to better explain exactly where their ‘line in the sand’ is drawn; and

- a lack of knowledge and confidence among many frontline officers to use their powers effectively.

In the light of these concerns, our conclusion is that the police do not strike the right balance on every occasion.

Does the current legislation give the police the powers they need to deal effectively with protests?

We found a wide range of views within the police as to whether the current legislation is adequate to deal effectively with protests. Forces that had experienced peaceful, non-disruptive protests had generally not had to resort to enforcement, and some interviewees told us they didn’t see the need for additional powers. Forces that had experienced significant disruption, confrontation and civil disobedience, on the other hand, considered the current legislation inadequate.

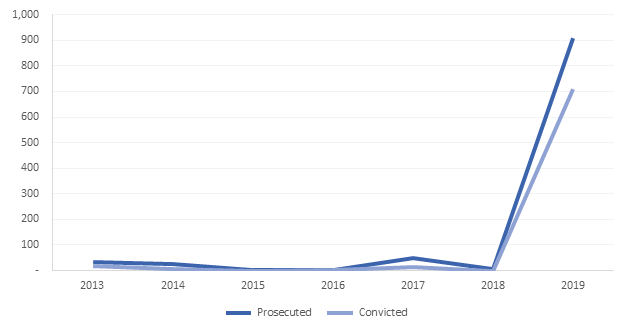

The data on protest-related arrests, prosecutions and convictions

The majority of large-scale protests take place in London, and therefore the Metropolitan Police used its enforcement powers more often than other forces. This was reflected in prosecution and conviction outcomes and was the trend in every protest-related offence we reviewed. The Metropolitan Police made most use of the current protest-related legislation, made most arrests, sought most prosecutions and secured most convictions.

There was very little recent arrest, conviction or prosecution data available to show the police actively using their powers under the following sections of the Public Order Act 1986:

- section 11 (the law that requires the organisers of public processions to notify the police in advance);

- section 12 (the law whereby the police can impose conditions on a public procession); or

- section 13 (the law whereby the police can apply to ‘prohibit’, or ban, a public procession).

There was more data, almost exclusively in relation to the Metropolitan Police, of the use of powers under section 14 (the law whereby the police can impose conditions on a public assembly).

The effectiveness of the criminal justice system in dealing with protest

Many police officers told us that they felt the criminal justice system was ineffective in dealing with the problems presented by protests. Some were severely critical of delays in the system, as well as defence lawyers’ tactics.

Some interviewees felt that the current sentencing, sanctions and penalties were ineffective, with little or no deterrent value. The majority of convictions for protest related offences incur penalties of low-level fines or − in very many cases – conditional discharges. The police felt that this did not act as a deterrent and could encourage unlawful behaviour at protests.

However, we also found that there was significant evidence of the Crown Prosecution Service bringing protest-related cases to court. These included fracking cases (mainly in Lancashire and Greater Manchester) and, more recently, Extinction Rebellion, Black Lives Matter and public health protests in London and elsewhere.

Five proposals for new legislation

Protest-related legislation has attracted considerable scrutiny and debate in Parliament, the Home Office and throughout the police service in recent years. In 2019, the Metropolitan Police, in consultation with and on behalf of the NPCC, provided the Home Office with “an overview of the challenges currently facing policing in light of the changing nature of protest”. They put forward 19 potential proposals that could “singly or in combination, address those challenges”. These potential proposals formed part of a wider collaborative debate throughout the police service, the NPCC and the Home Office. This resulted in the Home Office proposing five areas for legislative change.

The proposals were to:

- widen the range of conditions that the police can impose on assemblies (static protests), to match existing police powers to impose conditions on processions;

- lower the fault element for offences relating to the breaching of conditions placed on a protest of either kind;

- widen the range of circumstances in which the police can impose conditions on protests (again, of either kind);

- replace the existing common law offence of public nuisance with a new statutory offence as recommended by the Law Commission in 2015; and

- create new stop, search and seizure powers to prevent serious disruption caused by protests.

We were asked to review and offer opinion on these five proposals as part of our inspection. We looked closely at whether they would be compatible with human rights law, and their potential impact in Scotland and Northern Ireland. We concluded that, with some qualifications, all five proposals would improve police effectiveness without eroding the right to protest.

Two recommendations to align legislation so that the police have the same powers to deal with processions and assemblies

Our terms of reference enjoined us not to confine our review to the five proposed Home Office legislative changes. It isn’t just sections 12 and 14 of the Public Order Act 1986 (which form the basis of proposal 1 above) that treat assemblies and processions differently. The law, police powers and offences contained within sections 11 and 13 of the Act also apply only to processions and not to assemblies.

Our view is that organisers of assemblies should also have to notify the police in advance about their plans. We consider that this change would comply with human rights legislation and would not hamper the right to protest. Early notification by an organiser of their protest, whatever the type, would give the police and other public bodies with statutory obligations a better opportunity to plan.

The scale and type of public assembly (or procession) can and does vary. A common sense approach could be taken in the drafting and application of any new legislation to take these factors into account.

Recommendations

By 30 June 2021, the Home Office should consider laying before Parliament draft legislation (similar to section 11 of the Public Order Act 1986) that makes provision for an obligation on organisers of public assemblies to give the police written notice in advance of such assemblies.

We also think that the law should be changed to allow for the banning of an assembly, as it already does for a procession (only if the imposition of conditions will not be sufficient to prevent serious public disorder, and only with the consent of the Home Secretary). We consider that this would comply with human rights legislation if there were a framework of safeguards, thresholds and authorisation at the highest level. Extending the existing law in this way would have the potential to improve police effectiveness in keeping the public safe.

In conclusion, we see no good reason to continue treating assemblies differently from processions. It should be noted that Article 11 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) does not distinguish between them, referring only to a right of “peaceful assembly”.

In forming our views, we have taken account of governmental advice, published in July 2020, which reported that “increased polarisation of political discourse makes conflict and protest more likely and this may mutate into new and more violent forms” (see Chapter 6).

Recommendations

By 30 June 2021, the Home Office should consider laying before Parliament draft legislation (similar to section 13 of the Public Order Act 1986) that makes provision for the prohibition of public assemblies.

While offering qualified support for the five Home Office legislative proposals listed above, and making two proposals of our own, we emphasise that legislative reform will not be a panacea for the problem of disruptive protest. The police are constrained by resources as well as the law, and protest groups’ tactics will inevitably evolve.

Our views on additional police potential proposals for legislative change

We also offer a detailed review and opinion on three more of the 19 police potential proposals for legislative change that do not currently form part of the five Home Office adopted legislative proposals.

These are:

- Protest ‘zones’ or ‘schemes’ for London

We consider that a scheme to authorise protest buffer zones around locations such as Parliament could be framed in a manner that is compatible with human rights legislation. Widening such a scheme to cover other parts of London or sites of critical national infrastructure faces an increased risk of successful legal challenge.

- Protest banning orders

We agree with the police and Home Office that such orders would neither be compatible with human rights legislation nor create an effective deterrent. All things considered, legislation creating protest banning orders would be legally very problematic because, however many safeguards might be put in place, a banning order would completely remove an individual’s right to attend a protest. It is difficult to envisage a case where less intrusive measures could not be taken to address the risk that an individual poses, and where a court would therefore accept that it was proportionate to impose a banning order.

- Penalty notices for disorder for protest offences

We consider that the proportionate issue of penalty notices for disorder (PNDs) in appropriate cases is likely to be compatible with the ECHR. But, on balance, we consider that further research is needed before PNDs are used to enforce protest‑related offences.

Given the current public health emergency, the police experience of using fixed penalty notices for protest-related breaches of public health regulations may present an opportunity for such research.

Recommendations

By 30 June 2022, the Home Office, working with the National Police Chiefs’ Council and other interested parties, should carry out research into the use of fixed penalty notices for breaches of public health regulations in the course of protests. The research should explore the extent to which recipients complied with the scheme, and any consequential demand on the criminal justice system. The outcome of this research should inform a decision on whether to extend either the penalty notices for disorder scheme or the fixed penalty notice scheme to include further offences commonly committed during protests.

1. About the inspection

About us

Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services independently assesses the effectiveness and efficiency of police forces and fire and rescue services, in the public interest. In preparing our reports, we ask the questions that citizens would ask, and publish the answers in accessible form. We use our expertise to interpret the evidence and make recommendations for improvement.

Our commission

On 21 September 2020, the Home Secretary commissioned us to conduct an inspection into how effectively the police manage protests. Following various incidents that had caused disruption – including protests by Extinction Rebellion and Black Lives Matter – she required us to assess the extent to which the police have been using their existing powers effectively, and what steps the Government could take to ensure that the police have the right powers to respond to protests.

Recent protests

In April and October 2019, Extinction Rebellion brought some of London’s busiest areas to a standstill for several days. The policing operation for the two extended protests cost £37m, more than twice the annual budget of London’s violent crime taskforce. Police officers were extracted from other duties, including neighbourhood policing and investigations, in order to police the protest.

Nearly 8,000 Metropolitan Police officers were deployed during the October 2019 protest, and the Metropolitan Police had to draft in considerable support from other police forces. In April 2019, 1,148 activists were arrested, of whom more than 900 were charged, mostly receiving a conditional discharge. A total of 1,828 protesters were arrested in October 2019.

In September 2020, another co-ordinated action by Extinction Rebellion blocked the delivery of newspapers. This drew criticism from across the political spectrum.

In contrast to previous campaigns by other pressure groups, the tactic used by a significant proportion of Extinction Rebellion protesters was actively to seek arrest, in an attempt to overwhelm the police and justice system.

In recent years, increasing amounts of police time and resources have been spent dealing with protests. In addition to Extinction Rebellion, there have been long-running demonstrations against the badger cull, against companies involved in onshore oil and gas operations, and against the construction of the high-speed rail line, HS2.

Following the killing of George Floyd in the US, Black Lives Matter protesters took to the streets in British cities – and in some cases met counter-demonstrations by right-wing groups. The debate in respect of Britain’s relationship with the European Union has seen sustained pro- and anti-Brexit demonstrations in London and elsewhere, and there have been anti-lockdown protests in response to the COVID-19 restrictions.

Protest groups’ increased use of social media and online platforms have allowed protesters to keep up a constant flow of communication and to mobilise in a fluid way. In turn, police forces have changed the way they respond to protest, and they will continue to do so as these technologies evolve.

Police officers are often threatened, verbally abused, assaulted and injured – some seriously – when policing protests. For example, data held by the Metropolitan Police shows that, between 31 May and 11 December 2020, 280 police officers were assaulted at protests in London organised by Black Lives Matter, far-right protesters, the anti-lockdown group Stand Up X, and others.

The United Kingdom can reasonably expect more large-scale and sustained protests as the UK Government hosts the G7 summit in Cornwall in June 2021, and the United Nations climate conference (COP 26) in Glasgow in November 2021.

Protests are an important part of our vibrant and tolerant democracy. We all have the right to gather and lawfully express our views. But there are important questions for the police and wider society to consider in relation to how much disruption is tolerable and how to deal with unlawful behaviour at protests.

The human right to protest

The legal starting point in our democracy is that every person has the right to protest peacefully. There is no simple universal answer to the question: ‘When does a protest become unlawful?’ or ‘What restrictions can the police lawfully impose on protest activities?’

The domestic laws governing police powers to deal with protests are complicated to interpret and apply, having evolved in a patchwork manner over a long period of time. Importantly, as well as having a basis for action under domestic law, the police must also comply with the Human Rights Act 1998, which requires all public authorities – including the police – to act in a way that is compatible with the ECHR.

The fact that the UK has now left the EU does not affect the right to protest. The UK is still a signatory to the ECHR, which was signed in 1950 and pre-dates the EU.

The ECHR rights that are most relevant to the policing of peaceful protest are Article 10, which protects the right to freedom of expression, and Article 11, which protects the right to freedom of assembly. Both these rights are engaged when people protest. Article 9, the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion may be engaged by a protest. Article 8, the right to privacy, is also relevant in the context of police intelligence gathering against protesters. We have listed these four Convention rights in full in Annex A.

The police have a duty in certain circumstances to take active steps to safeguard the right to protest. If protests are peaceful, even if they cause a level of obstruction or disruption, the police are required to show a certain degree of tolerance. The degree of tolerance that should be extended is often the subject of extensive public and political debate.

None of the rights protected by Articles 8, 9, 10 and 11 is an ‘absolute’ right in the sense that it can never be restricted. In each case any interference with these rights must be prescribed by law and must be a proportionate means of achieving one of the legitimate aims listed in the relevant Article. This reflects the general principle inherent in the ECHR that seeks to strike a fair balance between individual rights and the general interests of the community.

Domestic law provides the police with powers to impose conditions on protests and to arrest protesters who commit offences. Whenever the police intervene in this way, they interfere with protesters’ human rights. The challenge for the police is always to do so in a proportionate, justifiable and lawful way.

This inspection has assessed whether the police are getting the balance right.

Terms of reference

This report considers five questions.

-

- How well do the police manage intelligence about protests?

- How well do the police plan and prepare their response to protests?

This includes the training, APP and other guidance, equipment and technology provided to officers.>

-

- How well do the police collaborate in relation to protests?

This includes mutual aid and other forms of collaboration between forces and other organisations.

-

- How effective are the decision-making processes and how do they affect the police response to protests?

This includes how well the police use their powers to police protests, enforce the law and minimise disruption to communities. It also includes how well the police balance the rights of protesters with the rights of other people, and the impact on communities, including minority groups.

-

- Does the current legislation give the police the powers they need to deal effectively with protests?

This includes an assessment of whether additional legislation would allow more effective policing of protests.

Methodology

We gathered a wide range of views and perspectives from the police, the public, protest groups and businesses affected by protests (listed in Annex B).

We inspected a sample of ten police forces in England and Wales. We interviewed POPS personnel and reviewed documents that show how they dealt with protests. We interviewed force solicitors. Most of the interviews were not carried out in person because of COVID-19 restrictions.

We also obtained evidence from some other forces with relevant protest experience. We observed police training courses. We saw a demonstration of police specialist cutting equipment.

We interviewed representatives from protest groups and reviewed documents that they provided. We also interviewed representatives from businesses affected by protest. We analysed data from the NPCC, police forces, the Ministry of Justice and the Police National Database.

We commissioned YouGov to conduct an online public survey to assess views on protest, disruption and the police response to protest. The survey took place between 27 and 29 November 2020, and included a sample of 2,033 respondents, representative of England and Wales (on a sample of this size, random sampling error is up to 2 percent). For more information on YouGov survey methodology, see YouGov’s website.

Definitions and interpretation of terms used in this report appears at Annex C.

Proposed changes to legislation

As part of the fifth question in our terms of reference, we were asked to comment on five proposed changes to legislation. If enacted, these changes may also affect Scotland and, to a lesser extent, Northern Ireland. Our commentary on the proposals appears in Chapter 6. We have included Police Scotland’s views and our explanations of some of the wider legal considerations for devolved administrations.

COVID-19

This inspection took place during the COVID-19 pandemic. Government restrictions on freedom of movement and limits on public gatherings changed the way the police approach protests for the duration of the pandemic.

We comment on the extra problems that policing protest under COVID-19 regulations has brought. COVID-19 policing is the subject of a separate inspection report.

2. Police intelligence about protests

This chapter contains our assessment of how effectively the police use intelligence to help them manage their response to protests.

The College of Policing’s Authorised Professional Practice (APP) on intelligence management describes intelligence as:

collected information that has been developed for action. It may also be classified as confidential or sensitive. Intelligence collection is a continuous process and there may be specific requirements for its recording and use.

In other words, intelligence is information that has been evaluated to assess its relevance and reliability. Intelligence and information gathering is so important that it is the first stage in a police decision-making process called the National Decision Model.

When dealing with the dynamic and complex nature of protest, police often have to make decisions based on publicly available information as opposed to assessed and graded intelligence.

In relation to the majority of protests, police intelligence gathering will only involve collecting sufficient information to help the protest pass safely.

However, a small minority of protesters are intent on arranging or carrying out more disruptive, violent or disorderly actions, which may involve varying degrees of criminality. For these protests, the information and intelligence needed by the police will be considerably increased.

The NPCC uses the following definitions in relation to unlawful activity associated with activism.

Aggravated activism is:

activity that seeks to bring about political or social change but does so in a way that involves unlawful behaviour or criminality, has a negative impact upon community tensions, or causes an adverse economic impact to businesses.

There are two levels of aggravated activism: low and high.

Low-level aggravated activism is:

activism which involves unlawful behaviour or criminality. This criminality is local or cross regional and potentially impacts on local community tensions.

High-level aggravated activism is:

activity using tactics to bring about social or political change involving criminality that has a significant impact on UK communities, or where the ideology driving the activity would result in harm to a significant proportion of the population.

For the purposes of our report, we use the term ‘aggravated activists’ to describe those who commit protest-related crime or unlawful behaviour. The most frequent level of aggravated activism associated with protests is low.

Activism comes in many forms, both lawful and unlawful. At the upper end of the scale are extremist, fundamentalist and terrorist activity, all of which fall beyond the remit of this report. In order to ensure that the UK is adequately protected against emerging terrorist threats, when intelligence relates to high-level aggravated activism, it is also shared with CTP for assessment. This is to identify escalating activity by groups or individuals that may indicate a path towards terrorism.

However, in this report, we only consider intelligence relating to largely peaceful protests, which may nevertheless involve an element of criminality and disruption.

The importance of gathering intelligence on aggravated activists

It is important that forces understand as fully as possible the risks that aggravated activists present to public safety, and their potential for disruption and criminality. For example, one protest group may pose a higher risk than another. Some protests predictably involve more disruption, economic loss, confrontation or disorder than others.

The police are better prepared to deal with this if they understand aggravated activists’ intentions. This means deploying officers with the right skills, in the right numbers, to collect intelligence, liaise with protesters, keep people safe and minimise disruption. The police need accurate, comprehensive intelligence on aggravated activists from a range of sources. This may sometimes involve covert sensitive intelligence-gathering methods, which include surveillance and the use of CHISs.

Aggravated activists often operate in more than one force area, so the police need good arrangements to co-ordinate intelligence gathering and disseminate it both within and between forces.

Case study: Newsprinters

This example highlights the difference that intelligence can make to the police approach. In this case, the police did not have intelligence about when and where a series of protests would take place. As a result, they were unable to intervene early. They had to mount a reactive rather than proactive response, which presented substantial problems.

Newsprinters is a printing company that operates from several sites throughout the UK. It is an affiliate of News UK and provides printing services for them, independent publishers and major newspaper groups. It prints some of the UK’s most-read newspapers.

In the months before the protest, Newsprinters liaised with the police about the possibility of protest at their sites. The protests did not materialise.

Representatives from Newsprinters told us, in relation to one of the forces involved: “Throughout the planning the police advised us of all the things they couldn’t do, the rights of the protesters and their limited powers against a legal protest.”

The police from that force told us they had worked with Newsprinters in the run-up to the planned protests. At meetings with the company, the police stressed their need to balance the rights of protesters and those going about their lawful business.

Just before 10.00pm on 4 September 2020, Extinction Rebellion protesters blocked the entrances and exits to Newsprinters at three sites using vans and a boat. Some protesters locked themselves to these vehicles. Others climbed temporary structures they had built from bamboo to make it more difficult for police to reach them.

The protest was targeted at national newspapers, which protesters accused of failing to report on climate change. The aim was apparently to maintain a blockade throughout the night, preventing newspapers from reaching shops and readers the following morning.

Police responded to the protests and used specially trained officers with cutting equipment to remove some of the protesters who had locked themselves to vehicles. Others unlocked themselves following negotiation with police. The protests lasted about 14 hours.

Newsprinters were far from satisfied with the police response from one force. They described a lack of regular updates during the protest at, what was for the company, a time-critical period.

Newsprinters told us there appeared to be a “lack of ability [by police] to tackle the situation and a greater concern on their part [the police] on the consequences of directly dealing with the protesters”.

The force concerned rejected the criticism and they told us they worked hard to remove many determined protesters from complex lock-on devices as quickly and safely as possible. Such was the challenge, officers were deployed from surrounding forces to assist with the lengthy removal operation.

In total, 79 protesters were arrested, and their cases are still progressing through the criminal justice system. News UK estimates that it incurred losses in excess of £1m as a result of the protests.

How effective are national arrangements for managing protest‑related intelligence?

Since the late 1990s, the police have made various arrangements for managing protest-related intelligence nationally. In recent years, this has fallen under the remit of Counter Terrorism Policing (CTP).

In January 2020, the NPCC decided to reallocate responsibilities. Low-level aggravated activism intelligence was transferred to the National Police Coordination Centre (NPoCC).

A promising start in difficult circumstances

The NPoCC’s strategic intelligence and briefing team (NPoCC SIB) was created in April 2020. Its remit is to manage intelligence related to low-level aggravated activists and protests that have the potential to cause disorder or significant disruption on a national or cross-regional scale. It is also responsible for giving intelligence and assessments to police forces. The transfer broadly coincided with the first national lockdown, which presented serious logistical problems for the new team.

Nevertheless, intelligence managers from the forces we inspected gave some positive feedback on the NPoCC SIB’s work so far. We heard from several officers that it had provided good-quality and useful intelligence in relation to protest activity, including from Black Lives Matter and Extinction Rebellion. One intelligence manager told us that, during the Black Lives Matter protests that took place throughout the country in summer 2020, the NPoCC SIB held national telephone conferences with forces to report on events and share information.

The NPoCC SIB produces and disseminates a weekly update to forces, containing an overview of relevant protests in their regions. Many officers we interviewed said that these updates had been effective, and that they had used them to help plan their approaches to protests and for briefings.

Officers told us that they would like more updates from the NPoCC SIB about tactics used by protest groups and the activities of known aggravated activists. This is a theme we explore in more detail later in this chapter.

The flow of intelligence to the National Police Coordination Centre’s strategic intelligence and briefing team

We did, however, find that the effectiveness of the NPoCC SIB is limited by the quality of intelligence it receives from forces. We found that the NPoCC SIB’s process for weekly intelligence collection is deficient in three respects:

- forces don’t always send the NPoCC SIB the intelligence debrief form that they should prepare and submit after each protest policing operation;

- even when they do submit the form, it often lacks detail; and

- the template that the NPoCC SIB sends to forces doesn’t explain clearly enough what information they need to provide.

We were encouraged to learn that the NPoCC SIB plans to redesign this template.

Forces do not always play their part in sharing intelligence with the NPoCC SIB. For example, on one occasion, the team asked forces that had experienced Extinction Rebellion protests to send them intelligence. Despite repeated requests, only three of the 12 relevant forces complied. The matter was eventually resolved when representatives of all 12 forces attended an NPoCC SIB-led debrief, where the team could gather the required intelligence. Clearly, the team can’t always do this, so it’s important that forces comply with requests for intelligence.

Areas for improvement

Forces should improve the quality of the protest-related intelligence they provide to the National Police Coordination Centre’s Strategic Intelligence and Briefing team. And this team should ensure that its intelligence collection process is fit for purpose.

How effectively do police assess protest-related risks using intelligence?

The police rely on intelligence to assess risks to public order, including protest-related risks. This assessment is recorded in a Public Order Strategic Threat and Risk Assessment (POSTRA). The police produce POSTRAs at force, regional and national levels.

Forces complete their assessments on a national template. Force-level POSTRAs are used to produce a regional assessment, which then feeds in to a national POSTRA. Some forces don’t produce their own POSTRA: they contribute instead to a regional assessment.

Changes to the way forces assess protest-related risks

Until April 2020, the national POSTRA was produced jointly each year by CTP and Essex Police, whose Chief Constable is the NPCC lead for POPS. They used the information from the regional assessments to produce the national assessment. The NPoCC SIB took over responsibility for producing the national POSTRA. It reviewed the POSTRA process and found problems with the quality of some of the force- and regional-level assessments. It has introduced a new process to resolve this.

We reviewed seven force and four regional POSTRAs. We found that they were generally not comprehensive or authoritative enough. Only two force and one regional POSTRA contained intelligence relevant to the protests forces had experienced during 2020. This was surprising, considering how much protest activity had increased during that year, with Black Lives Matter, Extinction Rebellion and anti-lockdown protests.

We asked forces to send us documentary evidence – such as agendas, papers and minutes of meetings – to show how they produce their POSTRAs. This showed that most forces discuss their POSTRA at certain meetings. However, we found little evidence that there was a detailed discussion of current intelligence relating to protest, or how this might affect areas such as training and the allocation of resources.

In interviews, some officers acknowledged that this area needed improvement. They compared the POSTRA with a similar risk assessment process concerning armed policing, which they found to be more thorough. They told us they would be improving their processes for public order by reviewing and updating their POSTRA documents more frequently. This should help to support the new process introduced by NPoCC SIB.

National intelligence gaps

During 2020, NPoCC SIB made major changes to the process for creating a national POSTRA, introducing a new document called the POPS Strategic Risk Assessment (POPSSRA). The term ‘threat’ has been removed to reflect its focus on legal areas and public safety. It places greater emphasis on intelligence held by police forces. NPoCC SIB expects this new national process to be fully operational by April 2021.

To cover the period until then, in December 2020, the team produced an interim POPSSRA. This was a more limited document, the team’s intention being to publish a more comprehensive version that would include more detail, such as forces’ protest‑related resource levels.

The interim POPSSRA contains commentary on the protest areas of:

- cultural nationalism;

- anti-fascism;

- animal rights;

- environmental concerns;

- anti-racism;

- European Union exit; and

- anti-government.

NPoCC SIB has established that there are intelligence gaps in various protest areas and therefore a need for police to improve sensitive intelligence gathering. This is reflected in the interim POPSSRA that was updated in February 2021.

Later in this chapter, we report on our findings regarding sensitive intelligence gathering.

How effectively do police manage intelligence on aggravated activists?

Intelligence gathering is not well co-ordinated across forces and regions. This is important because some protests are arranged on national (and international) lines spanning multiple force areas. A range of senior officers told us that, on a national level, there is a need to improve arrangements relating to the identification and targeting of the most prominent aggravated activists. Many such activists don’t just operate within single force boundaries.

For example, in September 2020, anti-lockdown protests took place throughout England and Wales. NPoCC SIB centrally co-ordinated the intelligence and disseminated it to forces for their information and action.

The unit identified a small number of aggravated activists who were encouraging conspiracy supporters to attend anti-lockdown demonstrations throughout the country.

Despite the work of NPoCC SIB, those aggravated activists identified to police forces repeatedly attended and spoke at demonstrations, travelling significant distances to do so across several force areas in breach of COVID-19 emergency legislation. NPoCC SIB established that a majority of forces dealt with them on their own. Better co‑ordination of police operations to target them, through disruption of travel, arrest, and co-ordination of bail conditions, would likely have reduced their criminality.

Plans to fill the gap

We found evidence that this lack of co-ordination existed before the creation of NPoCC SIB.

Between August 2011 and October 2020, 1,198 arrests were made across 17 forces in relation to protests about fracking. In total, 125 protesters were arrested at two or more separate locations, with 30 protesters arrested a total of 248 times between them.

Although these 30 protesters appeared willing to engage in repeated acts of criminality in connection with protests on a national level, they were not proactively targeted for intelligence gathering. Had this happened, forces might have disrupted their activities and prevented crime and disorder.

When the responsibility for managing protest-related intelligence transferred from CTP to NPoCC SIB, the new model did not include any intelligence co-ordination capability for aggravated activists. A senior NPoCC SIB officer told us that they recognised this shortcoming.

In January 2021, NPCC approved a modest increase in resources for NPoCC SIB to create a new ‘national development team’ on a 12-month trial basis. This team has the responsibilities to:

- provide co-ordinated intelligence capability to deal with aggravated activists; and

- explore the actual level of demand for this function.

We suspect that meeting the demand will require more resources, but it should help NPoCC SIB to perform a valuable function in managing the risks posed by aggravated activists.

Recommendations

By 30 June 2022, the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC), through its National Public Order Public Safety Group and National Protest Working Group, should analyse the results from the national development team trial. In the light of this analysis, the NPCC should secure an appropriate longer-term arrangement for managing the risks presented by aggravated activists.

How effective are intelligence arrangements at force level?

Forces allocate and prioritise intelligence resources differently. Protest is just one of the areas that forces’ intelligence units deal with. There are many others, including serious organised crime, modern slavery and child sexual exploitation.

Recent protests have stretched resources in most forces, and it can be a struggle for intelligence departments to balance competing priorities. This is the case even in the Metropolitan Police, which has significant resources allocated to protest intelligence.

We found some forces have officers and staff specifically allocated to dealing with protest intelligence; others don’t. Officers from some forces that have experienced significant protest activity told us that they have had to develop new protest intelligence capacity to meet the challenges.

Reliance on open-source research

The NPCC’s definition of open-source research is as follows:

The collection, evaluation and analysis of materials from sources available to the public, whether on payment or otherwise to use as intelligence or evidence within investigations.

In most of the forces we inspected, interviewees were positive about open-source research. They use it to provide information that helps them to produce their plans and relevant briefing material.

We do not underestimate the value of open-source research. But the police should draw on a wider range of sources to make sure that the information is accurate and to improve the intelligence picture. Officers told us that open-source research is the main source of intelligence about protests. They generally felt that it gave them enough information to respond. However, forces recognised that information gathered in this way may be inaccurate or purposely misleading.

The links between intelligence and planning

Interviewees in all forces told us that there were strong links between the protest intelligence processes and operational planning. Intelligence about protests is usually shared quickly, so that POPS commanders can make effective assessments about police response.

There is a mix of protest-related skills, knowledge and experience in intelligence units. Some POPS commanders told us, for example, that intelligence personnel do not always understand public order and the intelligence requirement for protests. They told us that this can affect the quality of intelligence products.

Echoing the views of other interviewees, an officer from one force told us that intelligence staff who don’t often deal with protests can be “out of their comfort zone” and need extra direction from commanders. In one force, we were told about plans to site intelligence officers in the planning team to improve their understanding.

Intelligence gathering takes place before, during and after an event. In addition to overt intelligence-gathering methods, like open-source research or asking for information from the protest organiser or the community, there are more intrusive options available to the police. Most protests are peaceful and conducted lawfully. In these circumstances, the use of such options cannot be justified.

We learned that all the forces we inspected have processes to gather information from their communities in which protests are planned to take place. Officers told us that community intelligence is an important piece of the intelligence picture. We found that neighbourhood/local policing teams play a major role in this.

Most interviewees told us that they were provided with valuable intelligence reports. These tended to include information that intelligence officers had collected from open‑source research about planned protests and protesters’ intentions. Commanders told us that, in addition to these reports, from time to time they also received useful intelligence updates during events from dedicated intelligence teams.

The use of forward intelligence team officers

We found there is a reluctance by POPS commanders in some forces to deploy forward intelligence team (FIT) officers. FIT is one of the tactical options available to commanders when responding to protests. The College of Policing’s APP outlines the role of a FIT officer, which is to:

- undertake overt information and intelligence gathering;

- identify and engage with individuals/groups who may become involved in or encourage disorder, violence, or may increase levels of tension;

- provide commanders with fast-time updates so that resources can be deployed efficiently and effectively; and

- provide information to assist in early resolution of events, e.g., arrests, release of contained persons.

It also gives guidance on how FIT officers should be deployed, advising commanders that their use may have a “significant impact on the public’s perception of police and their legitimacy”. It also states that commanders must ensure that the deployment of FIT officers is in accordance with the policing style of the operation.

Nine of the ten forces we inspected retained their own FIT capability. However, only three regularly deployed FIT officers to protests. Those we spoke to concluded that opportunities to gather intelligence were missed when FIT officers were not deployed.

In turn, however, commanders raised concerns that in deploying FIT officers they would run the risk of increasing confrontation with protesters. The commanders’ preferred policing style often places a strong emphasis on effective communication, negotiation and co-operation between police and protesters. The police refer to this as ‘engagement’.

A FIT officer’s job is not to co-operate or negotiate with protesters, but rather to gather intelligence. This may involve, for example, taking pictures of people and their clothing to establish the identity of individuals.

The role of police liaison teams

Police liaison teams (PLTs) are another tactical option available to POPS commanders when dealing with protests. The College of Policing’s APP outlines the role of a PLT officer:

- to provide a link through dialogue between the police and groups;

- is deployed before, during and after events to establish and maintain dialogue with groups, adopting a community policing style;

- reduces potential tension and the risk of disorder and conflict (e.g., avoiding misunderstandings, rumour control) and promotes trust and confidence in the police; and

- PLTs are not deployed to gather intelligence.

We examine the role of PLTs in support of police planners more in Chapter 3.

Due in part to commanders’ reluctance to use FITs, PLT officers are sometimes asked to gather intelligence. This blurs the boundaries of the role and may erode the trust that PLTs try to build up with protest groups. While being deployed in the role of PLT does not preclude an officer being involved in other policing activity, the role of a FIT officer is, and should, remain distinct from that of a PLT officer.

A range of officers, including a national role holder, a force public order strategic lead, and gold, silver and bronze commanders told us that confusion exists among some commanders about the different roles of FIT and PLT officers.

The image below, taken at a Reclaim the Power protest in Essex in July 2019, highlights some protesters’ distrust of PLTs. Officers carrying out this role wear blue bibs.

(Credit: Essex Police)

The development in a facilitative approach over recent years has meant that the use of the FIT as a tactic does not always complement that approach. While the primary focus of PLTs is not to gather intelligence as part of their engagement with groups, opportunities to do so should not be overlooked. We understand it can be a difficult balancing act for POPS commanders.

The police use of covert sensitive intelligence-gathering methods