A joint thematic inspection of the police and Crown Prosecution Service’s response to rape – Phase one: From report to police or CPS decision to take no further action

Contents

- Foreword

- Headline findings

- About this inspection

- Background information: an overview of rape investigation and prosecution in England and Wales

- The response to victims when they report a rape

- Police investigations

- Police decisions to take no further action

- CPS referrals

- Timeliness of case progression

- Communication between the police and the CPS

- Communication with the victim and appeals

- Keeping the victim informed of the progress of their investigation

- Communicating a police decision to take no further action to the victim

- Communicating to the victim a CPS decision to take no further action

- Police appeals of CPS decisions

- Victim appeals of police or CPS decisions (Victims’ Right to Review)

- Governance and leadership

- Resources and demand

- Training and continuous professional development

- Conclusion

- Definitions and interpretations

- Annex 1: Demographic information about the 502 case files we reviewed

- Annex 2: Methodology for phase one

- Annex 3: Methodology for our commissioned research with victims of rape

- Annex 4: External reference group membership

- Back to publication

Print this document

Foreword

This is the first of two inspection reports that will consider the response, decision‑making and effectiveness of the police and Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) at every stage of a rape case – from first report through to finalisation of the case. This report focuses on those cases where either the police or the CPS made the decision to take no further action (that is, not to proceed with the case). The second report, considering cases from charge to disposal, will be published in winter 2021.

In conducting this phase 1 inspection, inspectors from HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services (HMICFRS) and HM Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate (HMCPSI) gathered extensive evidence of the experiences of victims of rape in the criminal justice system. We traced their cases through police and CPS files, examining the decisions made and support offered at every stage. We commissioned research, to hear about victims’ experiences directly (and we are publishing a report of what victims and survivors told us alongside this report). And we asked police and the CPS, Government departments and victim representative groups for their own qualitative and quantitative data on what it’s like to report a rape in England and Wales today.

The results are clear. While we found examples of effective individuals and teams in every force and CPS Area, the criminal justice system’s response to rape offences too often lacks focus, clarity and commitment. We also found that it fails to put victims at the heart of building strong cases. This is despite the national focus by the Government, policing and the CPS on improving outcomes for rape.

Throughout our inspection, we found evidence of many dedicated people who were unwavering in their efforts to do the right thing for victims of rape, often in very difficult and challenging circumstances. This commitment and resolve to make improvements are to be commended and are worthy of note.

Overall, however, we conclude that there needs to be an urgent, profound and fundamental shift in how rape cases are investigated and prosecuted. More and more reviews, with more and more recommendations, may continue to refine processes – and we found clear evidence that this is needed in some areas (such as when communicating with victims). But these will not address the underlying problems we were told exist in the mindset of some police investigators and prosecutors towards rape cases.

This mindset is illustrated by the most common words used by frontline staff in both the police and CPS to describe rape cases: “really difficult”. We were told time and again that these cases were difficult to investigate, difficult to prosecute, difficult to explain to victims, and difficult for juries to understand.

The large number of reviews, reports and action plans that are in progress to address the serious problem of attrition levels between reported rapes and convictions both reflects and adds to this perception, which was described to us by one victim representative as resulting in ‘defeatism’ in the attitude of police and prosecutors towards these cases.

We are concerned that this mindset may be affecting police and CPS decision-making in many cases. We agree that rape cases can be – and often are – complex.

Some have significant evidential difficulties. But based on evidence from our case files, our interviews and focus groups, and from our knowledge of police and CPS practices more widely, we conclude that the police and CPS can be more cautious in their approach to investigating and prosecuting rape cases than they are towards other types of offences.

There are many reasons for this, including a lack of experience (some investigators, for instance, only investigate a very limited number of rape cases, and therefore have few opportunities to build their expertise). But we were also told that investigators and prosecutors are sometimes acutely aware of the heightened political and media attention on conviction rates, and on those very high-profile cases that fail, often with devastating effects on the victims or defendants.

Indeed, there should be scrutiny and openness to help ensure the response to rape is effective, and to bring about improvements in a system where the attrition rates are so high. But we believe this pressure is contributing to some investigators and prosecutors focusing on fully exploring all the weaknesses in a case, rather than on building strong cases. We saw examples of this in our review of what lines of enquiry were followed (or not) by investigators. It was also reflected in the level and breadth of evidence requested by the CPS in some action plans, which we sometimes found to be too broad and not sufficiently focused (and in a very small number of cases, to include requests for unnecessary information). Better, earlier and more regular communication between police and prosecutors would also help to sharpen the approach.

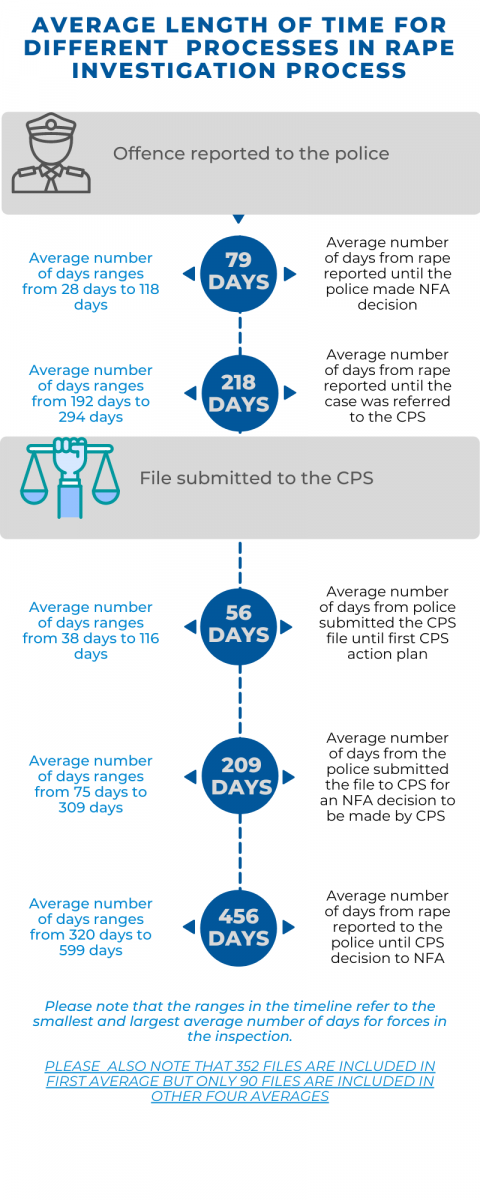

This more cautious and often unstructured approach adds delays to cases, as more and more information is requested. From our case file review, the average time from report until a case was closed with ‘no further action’ was 456 days. This is unacceptable.

Delays can also put immense pressure on victims. They described to us feeling under investigation themselves, and under more scrutiny when compared with suspects. In our case files, we saw examples of victims who experienced necessary but intrusive questioning and searches, who gave up their phones (sometimes for ten months or more), and whose medical records, therapy records and sexual histories were reviewed in minute detail.

By contrast, suspects are often not subjected to the same scrutiny during the investigation. It is of course absolutely right and necessary that the investigative process seeks evidence that can support prosecution of those reasonably suspected of an offence, whether such evidence points towards or away from a suspect. This requires the consideration of both the strengths and weaknesses of the case. The legal system also requires full disclosure of matters that are capable of supporting a suspects case or undermining the prosecution case. To victims, however, all too often investigations and prosecution decisions suggest a lack of belief and trust, as if it is their credibility which is the focus of the system. Some of those victims then withdraw support for the prosecution of their cases.

This creates a vicious circle. Concern about the low charge and conviction rates results in a cautious approach to rape investigations and prosecutions. This results in a disproportionate focus on the victim, which can then result in victims withdrawing support; which leads to worsening conviction rates. This cycle must be broken.

There is no single, easy answer to this, but several aspects would help (and we make recommendations to this effect):

- better data (to provide an improved understanding of when – and how – cases falter or fall out of the system);

- better information about the protected or other characteristics of those who report offences of rape, to understand whether victims with a range of different and/or complex needs are receiving an effective service;

- increased capability and capacity of specialist staff (especially among the police);

- joint training for the police and CPS; and

- improved communications locally between the CPS and the police.

These improvements must be coupled with a clear case strategy from the prosecutor at the outset of a case: the strengths of the case must be properly considered alongside action that could be taken to address potentially undermining information. This should be recorded clearly and accompanied by a proportionate action plan with rigorous target dates, which are regularly reviewed by both investigators and prosecutors.

But, fundamentally, we believe there are two essential catalysts required to achieve the necessary shift in prosecutions:

- a step-change in the quality and cohesiveness of joint CPS/police working at every level, with adequate capability and capacity in all parts of the system, and;

- the provision of high-quality and consistent ‘wrap-around’ care for those who report rape.

In terms of joint working, we saw some good examples at all levels of close and committed relationships between the police and the CPS (although this was inconsistent, and we make a series of recommendations aimed at urgently rectifying the situation). At the national level, there is a joint action plan in place for the CPS and police, and both organisation leads spoke convincingly of the need to work together to implement it.

However, this stated commitment is insufficient to overcome the deep division between the two organisations, which at present are seen by many as blaming each other for the low conviction rates. Interviewees from each side of the argument referred to different sets of data to defend these viewpoints. This approach suggests a lack of true acceptance of the fundamental need for joint ownership of the problems, and for a collaborative response to the systemic issues we have identified in this report. Until this blame culture is eradicated, a real shift in attitudes seems unachievable. Open acknowledgment of these deep divisions is a necessary first step.

In terms of victim support, we echo the recommendations of the 2020 report The decriminalisation of rape and the 2021 Improving the management of sexual offence cases (the Dorrian report) for the introduction of wrap-around support from the reporting stage. This resource should continue to support the victim regardless of the outcome of the case, and act as an intermediary not just with the criminal justice system but also with partner agencies and all organisations that can assist. Not all victims want a criminal justice outcome; proper support would recognise and adapt to this situation. Independent sexual violence advisers (ISVAs) are one model of providing this support; non-commissioned services are another. Regardless of the model chosen, they must be available, funded and trained, and the police and prosecutors must have a shared understanding of their role.

Such support would, we believe, result in a decrease in attrition rates for cases pre‑charge. In particular, it may have a positive effect on those cases involving ‘Outcome 16’ (the term used by the police for cases that are not continued because the victim does not support the prosecution), which made up about a third of our police case files (136 out of 352). To take no further action in these circumstances is a valid decision and overall we did not disagree with the rationale in the majority of cases we reviewed. But this outcome potentially masks a multitude of factors, and what was seldom explored was whether, with better support, these victims might have continued with the prosecution. The support provided must, of course, be sensitive to the victim’s needs.

Many of these findings are concerning in their familiarity. But there are some glimmers of hope. Among the many people we spoke with for this inspection, there was unanimous and unwavering determination to improve the response of the criminal justice system to victims of rape. And, while the multitude of reviews has added to the pressure on staff, the increased scrutiny has also resulted in some promising innovative work to address the problems identified (such as Project Bluestone, see ‘Police training’ section). The Joint National Action Plan, agreed between the police and CPS, also provides a significant opportunity for prosecutors and investigators to radically change the way they work together and with interested parties. The Government’s Rape Review (which was published while we were finalising this report, and to which we provided sight of our early inspection findings) makes commitments to closer and more coherent working throughout the criminal justice system.

Political and public interest in this area is high. Now is the moment to make the fundamental and lasting changes to the culture and approach to these cases that is so urgently required.

Headline findings

We found evidence throughout our inspection of many dedicated people who were unwavering in their efforts to do the right thing for victims of rape, often in very difficult circumstances. This commitment and resolve to make improvements are to be commended and are worthy of note. Overall, however, the approach to the investigation and prosecution of rape has to change.

The police don’t always get the first response to the victim right, and victims don’t always get the support they need.

The first contact between the victim and the police is critical as a means of building trust and building the case. If not correctly handled, opportunities to support and safeguard the victim may be lost. It can also affect the securing of evidence at this crucial stage. Although initial risk assessments were completed, referrals to support services were not always made. This could result in missed opportunities to share information that may give victims better support. Victims aren’t always given the reassurance and protection that pre-charge bail with conditions may afford.

Independent sexual violence advisers (ISVAs) play an important role in providing specialist tailored support to victims, but the ISVA service is not always fully understood by the police. Victims of rape are more likely to support an investigation when an ISVA is involved, but not all victims are referred to this, or other, commissioned services.

Governance and leadership across the criminal justice system at a national level are complex and fragmented.

The concerning attrition levels in rape cases have led to a significant number of interventions, and more scrutiny and national oversight, as parties seek to understand the reasons behind the worsening performance over recent years. Examples include the National Criminal Justice Board and the Joint Operational Improvement Board. Such is the level of commitment that each of these groups is chaired at a very senior level, including by ministers.

However, the net effect is that the work of these groups is not co-ordinated, and no single person has overall responsibility for holding the organisations to account for improvements. A more co-ordinated governance structure, with clear levels of accountability, and a single, identified, senior individual with the overarching responsibility and authority to hold all others to account, is required.

We are pleased to see that, following the Government’s The end-to-end rape review report (published June 2021), the Minister for Crime and Policing has been appointed as lead for implementation of the Rape Review. This is an opportunity to encourage close collaboration between all leaders from throughout the criminal justice system.

The relationship between the CPS and police service needs fundamental improvement.

The relationship between the police and CPS was described as collaborative at senior levels, with the work done by both organisations to develop the Joint National Action Plan cited as an example. However, despite all the work done by both organisations to improve, we found that each organisation still has an inward focus.

We also saw evidence of some difficult relationships between the police and CPS, with both organisations on occasion arguing that the other was ‘to blame’ for the low conviction rates. The development of the 2021 joint plan provides a foundation on which to build stronger relationships at all levels. In particular, at an operational level, a closer and more personal working relationship is required between the prosecutor and investigator to promote a joint approach to building strong cases, and better outcomes as a result. This would also help to build greater trust between both organisations.

Police and CPS resources cannot meet the demand, and investigators do not always have the right training or experience.

Workloads are often high and unmanageable. The lack of detectives and trained investigators results in many rape cases being dealt with by those without the right skills and experience. The training offered to investigators needs to be refreshed and reviewed. Prosecutors have large caseloads, which hampers progress, and many CPS Areas are carrying significant vacancies.

There is very limited joint training for the police and the CPS, which would provide another opportunity to build relationships between prosecutors and investigators.

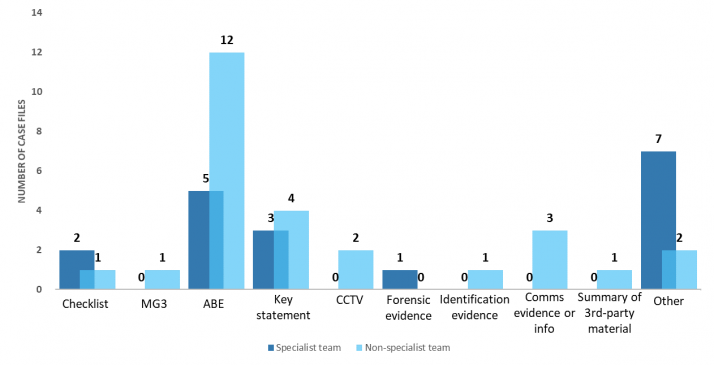

Forces that have specialist teams tend to perform better in certain aspects of the investigation of rape.

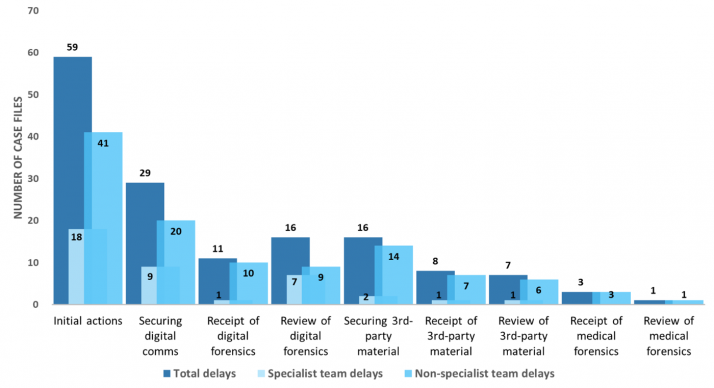

Specialist teams can lead to better decision-making, fewer delays and improved communication with victims and the CPS. Non-specialists may deal with too few cases to build their experience and expertise, and we found that cases dealt with by non-specialist teams incurred longer delays. The critical factor is to have enough trained specialist capability, with the support and capacity to do their work.

The absence of a victim-centred approach, founded on targeted specialist support for victims, is hampering the progress of cases. This can lead to victims being inadequately supported and either withholding or withdrawing support for cases.

In our review of police case files, one third of cases involved victims who did not support a prosecution. The police decision to take no further action because of this is called an ‘Outcome 16’. Without the support of the victim, it is very difficult to meet the evidential threshold needed to proceed with a case.

We saw cases where it was clear the victim did not want to be involved in a prosecution right from the start. In some cases, for instance, they hadn’t reported the offence themselves, but it had been referred to the police through a third party.

But in other cases we reviewed, victims did want to proceed with a prosecution when they first reported the offence, but later withdrew this support. The rationale for this was not always recorded. When reasons were given, they varied widely, from concerns about the time the process would take, to complicated relationships with the suspect, to wanting to focus on recovering from the incident rather than achieving a criminal justice outcome.

It takes immense bravery and resolve for victims to report rape offences. From our inspection, which also included interviews with interested parties and commissioned research with rape victims, we conclude that some of those who changed their minds about supporting a prosecution would probably have been able to continue with the case if they had been provided with better support. This may also have been possible in some of the cases where the victim indicated at the outset that they did not wish to go ahead with a complaint.

Worryingly, we found some cases that were closed quickly by the police when the victim had complex needs, such as mental ill health, and were unsure if they wanted to support the investigation. The wrap-around and bespoke support we are recommending for all victims should help better meet these victims’ needs and may therefore lead to more prosecutions.

In addition, the system of recording cases where the police have made the decision to take no further action fails to identify at what point the victim withdraws support. This is a missed opportunity to gather and use data in a focused way and provide tailored support to victims.

Police and prosecutors can be overly cautious in their approach to investigating and prosecuting rape cases. A shift to a more positive culture and mindset is required in an effort to build stronger cases and improve confidence in the system.

Many investigators and prosecutors told us that rape cases are ‘difficult to prosecute’ and were very aware of the criticism of low charge and conviction rates, and of high‑profile cases that have failed. As a result, the approach adopted sometimes appeared to be more focused on thoroughly exploring the weaknesses in a case, as opposed to focusing on the strengths of the case, building a positive case, and exploring the possibility of managing any problems.

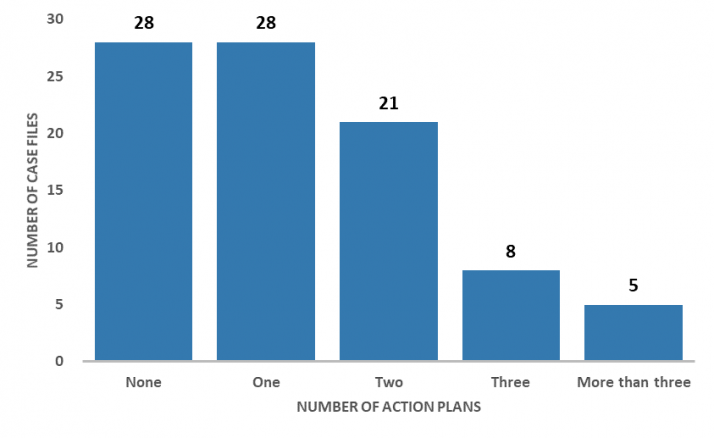

Unacceptable delays are occurring in cases, which indicate that better quality decision-making is required. The absence of a rigorous CPS case strategy in each case, underpinned by a clear, targeted and regularly reviewed action plan, results in significant delays and victims withdrawing support.

Action plans (which the CPS send to the police and include details of the extra evidence they want collected to help make a decision) are sometimes too broad – and on a few occasions in our review, asked for unnecessary information. This led to many victims feeling when interviewed that they were the person under investigation, which affected their confidence in the system.

We saw many examples of investigations being delayed at every stage of evidence‑gathering. Likewise, CPS decisions to take no further action aren’t always made quickly. Even when action plans are appropriate, the police are often slow to respond, which results in delays.

While communication and relationships between the police and the CPS at a senior level are good, we have concerns that this is not always the case between investigators and prosecutors. This affects how cases are dealt with and can lead to delays.

The suggestion that reviewing digital devices was a major cause of delays was not verified by our case file review.

Early investigative advice is not always understood by the police and is not used sufficiently.

Not making best use of early investigative advice is a missed opportunity for early engagement that could help the police understand what is needed to build a strong case.

The quality of police files provided to the CPS continues to be a problem.

There is clearly more work to do to bring the quality of many police files up to an acceptable standard.

Better and more consistent decision-making by investigators and prosecutors is required.

Investigators and prosecutors need to demonstrate that they are addressing myths and stereotypes and applying the guidance consistently.

There is some misunderstanding about the ‘admin finalised’ process, which the CPS uses when there is no response to action plans from the police.

The ‘admin finalised’ process does nothing to improve confidence in the way that the police and the CPS work together to progress cases.

A better shared understanding of data and performance information is required.

We found no single reason to explain either the decline in conviction rates, or geographical variation in referrals by forces to the CPS. Partly, this is because of a lack of consistent and robust performance data.

Police and prosecutors need to understand why, and at what stage, cases fall out of the system. This includes ensuring that officers and prosecutors understand the different outcome codes, and are better at explaining the reasons why a case has failed. Without that clarity, the organisations will be unable to learn lessons for the future. Both organisations should also be better at identifying the context for their performance. For example, an increased conviction rate may not necessarily indicate improved performance if fewer cases are pursued. If no open and transparent qualitative and quantitative set of data is available, which has been jointly agreed on, the organisations will be unable to gain a better shared understanding of what works and how best to build strong cases.

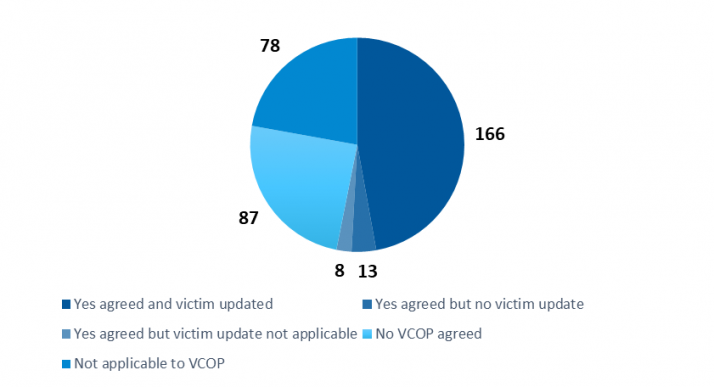

The quality of communication between the police and the victim, and between the CPS and the victim, needs to be improved. Too often, the decision to take no further action is not communicated well to the victim.

The police do not always tell victims that they have the right to review the no further action decision. It is vital that these decisions are explained sensitively to help the victim understand and come to terms with what has happened. Our commissioned research told us that most victims were negative about how well they had been kept informed by the police. For those victims who were more positive, they valued having a single point of contact, and clear explanations of the process when they needed it.

In most CPS cases, a letter was sent to the victim informing them of the decision to take no further action, but these were not always prompt and often lacked empathy or clarity.

Many of the victims’ groups we spoke with told us that they would welcome the CPS being more visible at a local level, which would promote better communication with victims, and also help build confidence.

Recommendations

There are many ways the criminal justice system can be more effective in investigating and prosecuting rape. These specific recommendations draw on how the investigation and prosecution of rape is currently handled and on our findings from this phase of the inspection, which focuses on those cases where either the police or the CPS made the decision to take no further action.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1

Immediately, police forces should ensure information on the protected characteristics of rape victims is accurately and consistently recorded.

Recommendation 2

Police forces and support services should work together at a local level to better understand each other’s roles. A co-ordinated approach will help make sure that all available and bespoke wrap-around support is offered to the victim throughout every stage of the case. The input of victims and their experiences should play a central role in shaping the support offered.

Recommendation 3

Police forces should collect data to record the different stages when, and reasons why, a victim may withdraw support for a case. The Home Office should review the available outcome codes so that the data gathered can help target necessary remedial action and improve victim care.

Recommendation 4

Immediately, police forces and CPS Areas should work together at a local level to prioritise action to improve the effectiveness of case strategies and action plans, with rigorous target and review dates and a clear escalation and performance management process. The NPCC lead for adult sexual offences and the CPS lead should provide a national framework to help embed this activity.

Recommendation 5

Police forces and the CPS should work together at a local level to introduce appropriate ways to build a cohesive and seamless approach. This should improve relationships, communication and understanding of the roles of each organisation.

As a minimum, the following should be included:

- considering early investigative advice in every case and recording reasons for not seeking it;

- the investigator and the reviewing prosecutor including their direct telephone and email contact details in all written communication;

- in cases referred to the CPS, a face-to-face meeting (virtual or in person) between the investigator and prosecutor before deciding to take no further action; and

- a clear escalation pathway available to both the police and the CPS in cases where the parties don’t agree with decisions, subject to regular reviews to check effectiveness, and local results.

Recommendation 6

The police and the CPS, in consultation with commissioned and non-commissioned services and advocates, and victims, should review the current process for communicating to victims the fact that a decision to take no further action has been made. They should implement any changes needed so that these difficult messages are conveyed in a timely way that best suits the victims’ needs.

Recommendation 7

Police forces should ensure investigators understand that victims are entitled to have police decisions not to charge reviewed under the Victims’ Right to Review scheme and should periodically review levels of take-up.

Recommendation 8

The National Criminal Justice Board should review the existing statutory governance arrangements for rape and instigate swift reform, taking into account the findings from this report and from the Government Rape Review. The recent appointment of the Minister for Crime and Policing to lead the implementation of the Rape Review should make sure that there is sustained oversight and accountability throughout the whole criminal justice system, sufficient resourcing for the capacity and capability required, and improved outcomes for victims. To support this, a clear oversight framework, escalation processes and scrutiny need to be in place immediately.

Recommendation 9

Immediately, the CPS should review and update the information on the policy for prosecuting cases of rape that is available to the public. The information provided about how the CPS deals with cases of rape must be accurate. Victims and those who support them must be able to rely on the information provided to inform their decisions.

Recommendation 10

Immediately, the College of Policing and the NPCC lead for adult sexual offences should review the 2010 ACPO guidance on the investigation of rape in consultation with the CPS. The information contained in available guidance must be current to inform effective investigations of rape and provide the best service to victims.

Recommendation 11

The Home Office should undertake an urgent review of the role of the detective constable. This should identify appropriate incentives, career progression and support for police officer and police staff investigators to encourage this career path. It should include specific recommendations to ensure there is adequate capacity and capability in every force to investigate rape cases thoroughly and effectively.

Recommendation 12

The College of Policing and NPCC lead for adult sexual offences should work together to review the current training on rape, including the Specialist Sexual Assault Investigators Development Programme (SSAIDP), to make sure that there is appropriate training available to build capability and expertise. This should promote continuous professional development and provide investigators with the right skills and knowledge to deal with reports of rape. Forces should then publish annual SSAIDP attendance figures, and information on their numbers of current qualified RASSO investigators.

Recommendation 13

The College of Policing, NPCC lead for adult sexual offences and the CPS should prioritise action to provide joint training for the police and the CPS on the impact of trauma on victims, to promote improved decision-making and victim care.

Next steps

There is a need for all component parts of the criminal justice system to adopt a dramatic shift in approach, so that significant and tangible changes are made. It is not just a case of maintaining the momentum of changes or recognising the problems; they must be owned and resolved together.

We have passed our inspection findings to the Government Rape Review to provide further information to help promote joint improvements throughout the criminal justice system.

The second phase of our joint inspection will focus on rape cases after charge, and our report will be published later in 2021. This will build on our findings from this first phase.

About this inspection

“The whole process is very distressing, and I felt a bit of relief when I was told it wasn’t going to go any further.”

Quote from a victim of rape

Why we inspected

Rape victims need to be able to trust in the criminal justice system to handle their cases thoroughly, fairly and effectively.

Reports of rape recorded by the police increased by almost 20,000 in the four years to March 2020. But at the same time, the number of rape cases referred by the police to the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) has decreased steadily.

More than 56,000 rapes were reported in the year to March 2020, and 4,181 were referred to the CPS for a prosecution decision. Of these, 2,325 cases resulted in a charge that year and 1,439 cases – or 3 percent of those recorded by the police – resulted in successful prosecution.

Missed opportunities for justice leave victims feeling badly let down and can contribute to their distress. And when a case doesn’t progress to court, it can mean that dangerous people remain free. There is no doubt that the current service provided to rape victims simply isn’t good enough. Why then do so many rape cases fail in the criminal justice system?

The problems surrounding rape investigation and prosecution in England and Wales have been intensively studied in scores of reviews over the past two decades. There is a high level of consensus in these reports, which have common themes and core recommendations. Despite all the work that has been done, successful prosecutions for offences of rape are at an all-time low.

Our last joint inspection to consider the prosecution of rape offences was published in February 2012, Forging the links: rape investigation and prosecution.

In December 2019, HMCPSI published a thematic review of rape cases (referred to in this report as the 2019 HMCPSI rape inspection report), which looked at the role of the CPS. To support understanding of the effect the police have on the CPS, a small, focused file assessment was undertaken by HMICFRS as part of that review. It was clear that further work was needed, and the report recommended that a joint inspection of the CPS and police response to rape should take place.

The Criminal Justice Joint Inspection (CJII) made a joint inspection of rape prosecutions a priority. This is because outcomes and public confidence in rape cases have deteriorated markedly in recent years.

How we inspected

Because of the urgency to explore what is happening with rape cases, we divided the inspection into two phases. Phase one examines what happens up to the decision to take no further action. Phase two will look at cases that were charged to their conclusion in court or otherwise. This report covers phase one only. Phase two is planned to take place in the year 2021.

In phase one of our inspection, we focused on answering three questions:

- What are the barriers to rape reports progressing to a decision to charge?

- Why does the volume of cases referred to the CPS for charging advice vary by police force and CPS Area?

- How well do the police and the CPS work together to prosecute reports of rape?

What we inspected

To understand the barriers to investigating and prosecuting rape, we inspected:

- how well police forces and the CPS understand the effect the criminal justice system can have on the victim and how well they support the victim throughout;

- whether there is effective leadership and governance to support the progression of rape cases through the criminal justice system;

- how effective police investigations are, and whether the police and the CPS are right to decide not to proceed with prosecuting a case;

- whether outcome codes for rape crime reports are applied accurately and consistently (to ensure there is an accurate understanding of why cases fail); and

- how effective police forces and the CPS are at progressing cases.

Methodology

Before we started fieldwork, we:

- commissioned a literature review to inform the scope of our inspection;

- established an external reference group with members from victims’ groups and other interested parties; we held three meetings where the group advised on our methodology and framework and made sure our inspection reflected the perspective of rape victims, and then considered our initial findings and subsequent recommendations; and

- commissioned an independent research company, Opinion Research Services, to support our work by evaluating adult rape victims’ (men, women, and non-binary) experiences.

We chose eight police forces in seven CPS Areas for fieldwork, using criteria that included some performance data, geography and demographics.

Our case file assessments examined rape cases defined by the Sexual Offences Act 2003 and recorded by the police where both the victim and suspect were adults at the time of the offence. The cases were finalised between May 2018 and November 2020.

The demographic information from the 502 case files reviewed is shown in Annex 1.

So that our findings reflect a range of experience, a team of inspectors from HMICFRS and HMCPSI:

- jointly reviewed and assessed 502 police and CPS case files from five police forces and CPS Areas in which it was decided to take no further action or cases were marked as ‘admin finalised’;

- held 39 interviews and 29 focus groups in eight police forces and seven CPS Areas with strategic and operational staff;

- held focus groups with independent sexual violence advisers (ISVAs) in six police forces; and

- held 13 interviews with national leads from the police and the CPS, Home Office and Ministry of Justice representatives, the Victims’ Commissioner for England and Wales, the College of Policing and national representatives of victims’ groups.

The COVID-19 pandemic meant we couldn’t visit three of the police forces. For these forces, our teams did the fieldwork and case assessments remotely.

Annex 2 provides more information on the methodology used for this inspection.

About the quotes in this report

The quotes in this report are from people with experience of rape. We asked Opinion Research Services, our commissioned researchers, to record victims’ thoughts and comments about their experiences of the criminal justice system.

Annex 3 sets out more detail on the methodology used for this commissioned research.

About the terminology and approach we use in this report

We recognise that there are discussions over the use of ‘complainant’, ‘victim’ and ‘survivor’, and of ‘suspect’, ‘accused’ and ‘defendant’. Throughout this report, the term ‘victim(s)’ is used to refer to those affected by rape. It incorporates other terms such as ‘complainant(s)’, ‘client(s)’ and ‘survivor(s)’, as referred to by focus groups and interviewees. We have used the term ‘suspect’ to refer to a person accused of rape. It incorporates ‘offender’, ‘perpetrator’ and ‘defendant’. Other terms may be used when referring to published data or in quotes to maintain consistency with the original source.

Background information: an overview of rape investigation and prosecution in England and Wales

“To the CJS, you’re just another case, another victim.”

Quote from a victim of rape

Numbers of rape offences recorded, referred to the CPS, charged and successful prosecutions

The number of rape offences recorded by the police decreased from 59,492 offences in the year ending March 2019 to 56,061 rape offences (−3,431) in the year ending March 2020, according to figures published by the Home Office. However, previous years have seen large increases in the number of rape offences reported to the police, including an increase of 23,215 offences from 2015/2016 to 2018/2019.

Figure 1: Rape offences recorded by the police from 2015/16 to 2019/20

Source: Home Office published data

Of these 56,061 rape offences, the police referred only 4,181 to the CPS in the year ending March 2020. The number of referrals has been decreasing in recent years; the year ending March 2019 recorded 5,109 referrals, the year ending March 2018 recorded 6,012 referrals and the year ending March 2017 recorded 6,606 referrals.

There were 2,325 charges for rape offences recorded by police in the year ending March 2020. This is similar to the 2,319 charges recorded in the year ending March 2019. While the number of charges has decreased in recent years, the charge rate has remained stable.

There were 1,439 successful prosecutions recorded in the year ending March 2020 for rape offences; this is 486 fewer than the 1,925 successful prosecutions recorded in the year ending March 2019.

Figure 2: Rape figures for the year ending March 2020

Source: Home Office, Crown Prosecution Services and Ministry of Justice data

The role of the police in investigating rape

The police are responsible for maintaining public order and safety, enforcing the law, and preventing and detecting criminal offences. There are no national police services, but 43 separate police forces in England and Wales. The police conduct investigations into any alleged crime and decide how to deploy their resources. This includes decisions to start or continue an investigation and the scope of the investigation. Each force has a chief constable (or commissioner) who is held to account by a publicly elected police and crime commissioner (PCC) or mayor. Some forces have specialist rape and serious sexual offences (RASSO) teams, comprising investigators who work solely or mostly on cases involving these offences. Others do not, and rape cases are instead handled by investigators in general teams. We comment further on this in the ‘Resources and demand’ chapter.

PCCs are responsible for securing efficient and effective policing of a police area. They create and publish plans for each force, which outline their priorities and how they will work with partner agencies to achieve them.

Police decisions on whether to refer a case to the CPS for a charging decision

The Code for Crown Prosecutors (the Code) sets out the principles to be followed for a charging decision to be made. The decision has two stages: the evidential stage and the public interest stage. The police must gather all relevant evidence, regardless of whether such evidence points towards or away from a suspect. This requires the consideration of both the strengths and weaknesses of the case. The police must assess whether the evidential test is met on the available evidence. If it does not meet this test, they should make the decision to take no further action without referral to the CPS. Most rape investigations are finalised by the police at this stage.

Figure 3: Rape offences recorded: how many were referred to the CPS and the number of successful prosecutions from 2015/16 to 2019/20

Source: Home Office and CPS data

If the police conclude that the evidential test is met, the case is passed to the CPS for a charging decision.

The role of the CPS in prosecuting rape

The CPS is the national and independent body which is responsible for the prosecution of criminal offences that have been investigated by the police throughout England and Wales. It is led by the Director of Public Prosecutions and consists of headquarters’ teams and 14 regional teams prosecuting cases locally. Each of these 14 CPS Areas is headed by a chief Crown prosecutor and has a dedicated RASSO team to deal with rape and serious sexual offences.

The CPS forms one of the ‘Law Officers’ Departments’ and, as such, constitutes a public arm’s length body subject to the statutory superintendence of the Attorney General. There is a framework agreement that sets out the main points of the relationship. Internally, the CPS has a strategic board which is chaired by a non‑executive director and an executive group. Both the framework agreement with the Attorney General and the board structures within the CPS form a system of control and accountability.

The CPS is responsible for charging serious offences, which includes all offences of rape. The CPS has a role in advising the police during the early stages of investigations but can’t direct an investigation. After charge, the CPS prepares cases and presents them at court. It provides information, help and support to victims and prosecution witnesses.

CPS decisions on whether charges should be brought

Before authorising a charge, a Crown prosecutor must be satisfied that there is enough evidence to provide a ‘realistic prospect of conviction’. They must assess whether the evidence can be used and is reliable. They must also consider what the defence case may be and how it is likely to affect the prosecution case.

A realistic prospect of conviction is an objective test. It means that a jury or a bench of magistrates, properly directed in accordance with the law, will be more likely than not to convict the defendant of the charge alleged. This is a separate test from the one that criminal courts themselves must apply. A jury or magistrates’ court should only convict if it is sure of a defendant’s guilt. If the case doesn’t pass the evidential stage, it must not go ahead, no matter how important or serious it may be.

If the case passes the evidential stage, a decision is taken about whether a prosecution is in the public interest. Factors for and against prosecution must be balanced carefully and fairly. It will nearly always be in the public interest to charge an offence of rape.

CPS guidance sets out how prosecutors should apply the Code to rape and other sexual offences to build and present cases that are based on strong evidence. Prosecutors are obliged to disclose material that might reasonably be considered capable of undermining the case for the prosecution or assisting the case for the suspect.

Recent changes to guidance and guidelines related to the investigation and prosecution of rape

At the time of our inspection there was a great deal of fast-paced change, partly in response to the intensive and multiple reviews of rape cases in the criminal justice system (we say more about this in the ‘National review’ section). In a three-month period, several important new guidelines were published which change how rape cases are handled.

In October 2020, the CPS published interim legal guidance for handling rape and serious sexual assault (RASSO) cases that was subject to public consultation.[1] The guidance must be read alongside several other documents, including the Protocol between the police service and Crown Prosecution Service in the investigation and prosecution of rape (PDF document) (2015).

The Director’s guidance on charging (6th edition) (DG6) and the Attorney General’s guidelines on disclosure came into effect on 31 December 2020. These documents apply to all criminal investigations and prosecutions, including rape. They introduced significant changes for the police and the CPS. DG6 introduced changes to how the CPS and the police work together at the beginning of the investigation process. This is discussed in more detail later in this report.

These guidelines weren’t in place at the time of our fieldwork and so none of the files we reviewed reflected these changes. It will take time for the full effect of them to be seen in cases.

[1] This interim guidance has now been replaced by updated legal guidance published on 21 May 2021.

The response to victims when they report a rape

“I wanted justice. I wanted him to have consequences for what he had done.”

Quote from a victim of rape

“I felt that the incident was holding me back from moving on with my life. So I sought some support for it and off the back of that I made the decision that I wanted it acknowledged and wanted to report it.”

Quote from a victim of rape

People report rape to the police for many different reasons. These include because they:

- have been encouraged to by others;

- think it is the right thing to do;

- want to protect others;

- want closure or an official record of the incident; and

- want justice or for the suspect to face consequences.

Our inspection focused on improving outcomes for all victims of rape, regardless of why they reported, their demographics or the circumstances of the offence.

Getting the first response right is crucial

“I felt very believed, which was an important factor in me carrying on.”

Quote from a victim of rape

“The police lady that came over was so nice and lovely. She took her time with me, didn’t intimidate me and put me at ease. I felt that she respected me and was understanding about what I’d been through. She made sure I was alright after asking every question. They did everything they could at this stage, and I thought it was done well. At this point I thought that maybe things were going to go well.”

Quote from a victim of rape

“It was quite horrible. It felt like they were asking questions about unnecessary things. They asked the same things and felt like they weren’t accepting my answers. I felt judged. I walked away feeling worse and heavier, like I shouldn’t have reported it.”

Quote from a victim of rape

“The police [officer] was quite rude to me. That wasn’t very nice. She was implying that I was making it up. It was just her whole attitude to things.”

Quote from a victim of rape

“The police didn’t get to me for a few months after I reported it! At that point I almost dropped out completely because I thought they saw me as stupid and didn’t care enough to respond. It made me feel like maybe it wasn’t serious enough or that they thought I was lying.”

Quote from a victim of rape

The first police response to victims of rape is critically important. Our research showed that it can greatly affect how a victim feels and can influence their decision whether to take the case forward. Every report of rape is unique. But the main objectives for the police are always the same, namely to:

- make sure that the victim is safe;

- secure and preserve evidence; and

- identify and arrest (or, if appropriate, voluntarily interview) the suspect.

When the police get a report of rape, they should record it as soon as possible. After getting a report of rape in the police control room, officers usually complete an initial THRIVE assessment and allocate resources. THRIVE is an assessment based on threat, harm, risk, investigation opportunities, vulnerability of the victim, and the engagement needed to resolve the problem. How quickly the police respond depends on this assessment.

Our inspectors found that forces couldn’t always send officers with the right skills. We were told that the first attending officer to a report of rape could be a response officer with enhanced training in sexual offences, or a specialist investigator. But if no trained officer was available, the first responder might be an officer without the skills, knowledge or confidence to support victims or understanding of where to signpost the victim to services that can offer support.

In our focus groups, we heard from specially trained officers who felt confident in providing the crucial first response, understanding the process and informing the victim of what would happen. By contrast, we also heard from an officer who had responded to a report of rape and had treated the victim just as they would any victim of an assault, as they didn’t have the training or experience to do otherwise.

Our inspectors found that, in most cases, the initial actions to secure evidence, such as getting CCTV footage and making house-to-house enquiries, were completed well by the attending officer. But we saw some cases where officers couldn’t respond straight away, and the delay meant losing opportunities to make sure the victim was safe and to collect vital evidence.

Case study

The victim’s mother contacted the police with concerns for her daughter’s safety. Police attended to check on her welfare, and the victim reported that she had been raped 10 days earlier by her stepfather. While officers were there, the victim had a panic attack and assaulted the officers, so she was arrested. Over the following week she was spoken to on several occasions, but finally said she didn’t wish to make a complaint or attend court.

The sole focus in the case was on whether the victim wanted to make a formal report of rape. The police didn’t secure any evidence at the time, including Facebook messages where the suspect had apologised for what he had done, or speak to important witnesses. While the focus should be directed towards the victim and securing their welfare, the police shouldn’t ignore investigative opportunities. Had the victim later changed her mind and supported police action, this evidence might have been lost.

We also saw cases where the victim later withdrew support for the allegation without being spoken to by the police. This highlights the importance of speaking to victims as soon as possible. Some victims from our research felt that the police should have provided more important information about the statement process. Victims were more positive about giving a statement when police officers were kind and considerate towards them, allowed someone to accompany them and offered tailored support.

Recording reports of rape where victims have protected characteristics

Before we started our inspection, we were aware that some victims with protected characteristics (see below) may face greater barriers when reporting rape offences.

Protected characteristics include age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex and sexual orientation.

In our case file analysis, we found that gender was recorded for all victims. However, ethnicity wasn’t recorded for the victim in 167 of the 502 cases, and for the suspect in 194 cases.

Other than gender and ethnicity, we found the following recorded protected characteristics:

- disability: in 57 cases;

- mental health: in 26;

- sexual orientation: in 12;

- gender re-assignment: in 3; and

- religion or belief: in 3.

While more than half of cases were positively identified as having no other protected characteristics, this was unknown in a large proportion. We found that there is insufficient and inconsistent evidence of forces seeking to understand the profile of victims and whether they have protected characteristics.

Accurately recording protected characteristics is very important and can affect many aspects of the case for the victim. This includes how well the police understand the prevalence of rape, contributing to rape profiles and how the police respond. But its main value is in better awareness and in helping victims get the right support.

Urgent and immediate improvement is necessary, and we make a recommendation to that effect.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1

Immediately, police forces should ensure information on the protected characteristics of rape victims is accurately and consistently recorded.

Our small sample size meant we couldn’t make any assessment about any differences in outcomes without more detailed inspection activity in these specific areas.

Safeguarding and support

In most cases, the initial risk assessments for victims were completed. But as shown in Figure 4, not all safeguarding referrals, such as to adult social care, were made when appropriate. This is a missed opportunity to share information with partner agencies so that areas of concern can be addressed, and wider support given to victims.

Figure 4: Was a safeguarding referral made?

Source: Data taken from our case file review analysis (352 files)

We did find some positive examples of cases where wider safeguarding was considered, and action taken.

Case study

The victim, who was a sex worker, reported being raped by two unknown men. The police conducted a thorough and focused investigation but couldn’t identify the offenders. We saw evidence that the victim was supported sensitively throughout the investigation, and that wider safeguarding was used well. This included contact with National Ugly Mugs (NUM), a charity that provides greater access to justice and protection for sex workers who are often targeted by dangerous people, but who are often reluctant to report these incidents to the police. This allows NUM to post an alert on their website and contact members of the scheme to raise awareness of dangerous offenders.

After the first police attendance, the victim may go to a rape support centre, or a sexual assault referral centre (SARC). The role of the SARC is to provide a safe and secure environment where victims get the help and support they need while evidence is being gathered. Assessing SARCs wasn’t within the scope of this inspection,

but we heard from officers and investigators that the SARC function is recognised as effective. Similar positive reports came from survivors who reported that SARCs provide holistic, person-centred support that doesn’t just focus on the incident.

Forces don’t always involve independent sexual violence advisers effectively

“I would have continued with it if I’d had the support, but I didn’t. If I’d known about the Survivors Network, where my ISVA is from, if I’d known about all these charities who could help … I was completely clueless about it because this had never happened to me before.”

Quote from a victim of rape

The police service has an obligation to refer victims to appropriate support services, such as independent sexual violence advisers (ISVAs), under the Code of Practice for Victims of Crime (Victims’ Code, see ‘Keeping the victim informed of the progress of their investigation‘ section). Failure to refer victims to support services is a breach of the Victims’ Code.

But we found inconsistent levels of referrals to support services, and especially in the effective involvement of ISVAs. Our commissioned research showed the same thing. Some victims were disappointed that the police or support services didn’t direct them to ISVAs.

ISVAs have an important role to play in providing specialist tailored support to victims of sexual violence. The nature of the support varies from case to case depending on the needs of the person and their circumstances. ISVAs provide continuity and ongoing advocacy, impartial advice and information to victims. They also give information on other services that victims may need, for instance to help improve their physical and mental health, overcome addiction concerns, or assist with questions about social care, housing or benefits.

We found victims of rape are more likely to continue to engage with the police and support an investigation when an ISVA is involved. We welcome the announcement in the 2021 Government Rape Review of new government funding for more ISVAs and domestic abuse advisers.

“I probably wouldn’t have reported if I hadn’t been in touch with [support worker]. Being able to get the first meeting through [support worker] was the first baby step in encouraging me to go through the whole process.”

Quote from a victim of rape

“My ISVA explained the whole process to me, of what happens when I go to the police, what happens afterwards. She was so good at explaining what I can do, and how she can support me through it.”

Quote from a victim of rape

We talked to ISVAs in our focus groups and heard that relationships with the police vary between forces. We heard some positive accounts of ISVAs and the police working well together, with bespoke training and joint performance meetings. This is important in helping to ensure the police are informed by, and act on, the experiences of victims.

But there were too few reports like this. Relationships too often depended on the individual investigator’s understanding of the ISVA role. Less than a third of the case files we reviewed showed evidence of regular communication between the police and ISVAs over the course of the case. The examples of good communication were mostly in forces that had specialist police teams. In these forces, we heard of good, positive links between the police and ISVAs. This resulted in bespoke support for survivors, including access to wider support services.

We found it worrying that some ISVAs felt that investigators didn’t always understand their role. They reported that some investigators saw the service as ‘stamping through their investigations’ and were dismissive of the support they could provide.

Our focus groups with first response officers and investigators found inconsistent knowledge and awareness of how to refer to victims and what services were available.

Recommendations

Recommendation 2

Police forces and support services should work together at a local level to better understand each other’s roles. A co-ordinated approach will help make sure that all available and bespoke wrap-around support is offered to the victim throughout every stage of the case. The input of victims and their experiences should play a central role in shaping the support offered.

Using pre-charge bail to protect the victim

In most of the cases we reviewed where suspects were known, and the victim supported police action, the suspects were arrested quickly. After arrest, the police can consider using pre-charge bail with conditions, including the condition that the suspect is not to contact the victim. Although we found pre-charge bail was used well in most cases, many of these later automatically reverted to released under investigation (where no conditions can be imposed) after 28 days, without any documented rationale or a new risk assessment. This leaves many victims without the reassurance and protection that bail conditions can provide. In the cases we reviewed where domestic abuse was a factor, we found evidence that Domestic Violence Protection Orders (DVPOs) and Domestic Violence Protection Notices (DVPNs) were not always considered or used when they should have been.

Police investigations

“I would have expected the police to have specialists in sexual violence – almost like a mediator and more focused on well-being rather than wanting to go into what happened straight away.”

Quote from a victim of rape

Investigation plans

After the police initially respond, the case it then passed on to an investigator to progress. Investigation plans are made by the investigating officer or their supervisor and are used to highlight lines of enquiry needed to further develop the investigation.

In our case file assessments, we found that investigation plans were recorded in more than three quarters of the investigations. But we saw a variance in the quality of these plans, ranging from clear direction and focus to a lack of detail and little guidance. We found some evidence that the investigation plans completed by specialist teams were of a better standard.

Figure 5: Did the investigation plan include all lines of enquiry?

Source: Data taken from our case file review analysis (442 files)

Supervision

In more than a quarter of the case files we reviewed, investigators did not have the right training. This means that strong supervisory oversight and guidance was even more essential. One supervisor told us that “new police constables are dealing with rape cases. It’s not good for victims”.

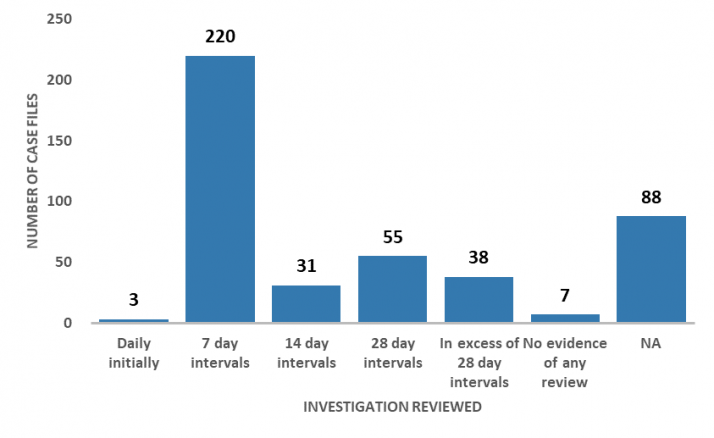

Over half of the investigations we reviewed had an entry from a supervisor every seven days. But these entries were, on many occasions, just to satisfy an administrative requirement. They didn’t add value or guidance to the officer or the investigation process. This meant that investigations could drift in focus and pace.

Figure 6: How regularly was the investigation reviewed by a supervisor?

Source: Data taken from our case file review analysis (442 files)

Case study

The victim reported a rape by her partner in September 2018. The initial investigation was dealt with swiftly and appropriately in the early stages. The victim had a medical examination and gave her account by way of a video interview early. The suspect was arrested the day after the report. But the case was assigned to an inexperienced investigator. In November 2018, the case was referred to the CPS, who returned an action plan sent to the police to complete further enquiries. One year on from the reported rape, it is clear there has been no meaningful investigation and that there is a lack of supervisory oversight and direction. In January 2020, the victim withdrew her support for the investigation and the case was finalised by the police.

In our focus groups, some supervisors spoke of unmanageable workloads that make it difficult for them to do the necessary reviews. A detective sergeant told us they didn’t have the capacity to oversee all investigations because of the volume of cases. And many supervisors don’t have enough experience or the right training to add value to the investigation process.

Use of early investigative advice

Since its introduction, early investigative advice has been under-used. In our case file assessments, it was only requested in 12 out of 90 cases.

Early investigative advice from prosecutors can guide the police in determining what evidence they need to support a prosecution. Provision for it was made in the Director’s guidance on charging (5th edition, 2013). This guidance states that cases involving rape should always be referred to a prosecutor as early as possible. Early advice should focus on the evidence needed and reduce delays.

Figure 7: Why was the case first referred to the CPS?

Source: Data taken from our case file review analysis (90 files)

One force told us that, in the past, requests for early investigative advice had overwhelmed the CPS, causing backlogs. Because of this, the force no longer asks for early investigative advice. It tends to be asked for too late and the CPS takes too long to provide it, which defeats the aim. Our findings highlight that this perception is likely to result in investigators not having the confidence or desire to seek early investigative advice.

We found that there is no standard process for what documentation the police need to submit to obtain early investigative advice.

Some investigators and prosecutors said that they did not expect early investigative advice to be effective in progressing cases. Some investigators said that to obtain early investigative advice they had to prepare a full file of evidence for the CPS, which is clearly wrong and suggests the intended purpose is misunderstood. This failure by both the police and the CPS is a missed opportunity for early engagement that could help the police understand what is needed to build a strong case. It can lead to unacceptable delays in the decision-making process and be harmful for the victim.

Ineffective use of early investigative advice has been a recurring theme in inspection reports. The 2019 HMCPSI rape inspection report recommended changes including the CPS providing greater clarity about timescales and what documentation is needed.

We welcome the introduction of the Director’s guidance on charging (6th edition) (DG6), which came into force on 31 December 2020, after our inspection. The guidance aims to give better practical information to the police and the CPS on their charging responsibilities. Early investigative advice has been renamed ‘early advice’ and the process for obtaining it is clearer. Police supervisors and prosecutors must make sure there is an audit trail. The Police-CPS joint national RASSO action plan 2021 aims to develop this, providing additional guidance on early investigative advice and reasonable lines of enquiry so that strong cases are built from the start. Whether this new guidance is effectively implemented and brings improvements will need to be assessed in the future.

There is a risk that the CPS may be overwhelmed with requests for early advice, as the new guidance ‘strongly recommends’ that it is provided in all rape cases. The CPS already battles backlogs of cases and difficulties caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. We understand that the CPS has had extra funding to improve its response to rape and serious sexual offences, which should help keep this risk to a minimum.

The police and the CPS must work together so that early advice is sought and provided in the right cases to make the best use of limited resources.

Police decisions to take no further action

Background information: Outcome codes

When an investigation is completed, the case gets an outcome code under Home Office Counting rules. These rules are a national standard for recording and counting notifiable offences recorded by police forces in England and Wales (known as police recorded crime). Outcome codes record the reasons that crime investigations have been finalised.

The investigations reviewed by inspectors consisted of outcome codes 14, 15, 16, 18 and 21:

- Outcome 14: Evidential difficulties – suspect not identified. The victim doesn’t support further action (from April 2014). The crime is confirmed but the victim declines to or can’t support further police action to identify the offender.

- Outcome 15: Evidential difficulties – named suspect identified. The crime is confirmed and the victim supports police action, but evidential difficulties prevent further action.

- Outcome 16: Evidential difficulties – named suspect identified. The victim doesn’t support (or has withdrawn support for) police action.

- Outcome 18: Investigation complete – no suspect identified. The crime has been investigated as far as reasonably possible and the case closed pending further investigative opportunities becoming available.

- Outcome 21: Not in the public interest – suspect identified (from January 2016). Further investigation resulting from the crime report that could provide enough evidence to support formal action being taken against the suspect isn’t in the public interest – police decision.

Figure 8 shows the number of police recorded outcomes in England and Wales for outcome codes 14, 15, 16, 18 and 21, and the outcome rates for these same outcome codes. Rape offences were finalised with an outcome 16 in 16,076 cases, with an outcome rate of 29 percent. These figures pertain to outcomes assigned to rape offences in the year ending March 2020 and there are still over 19,000 rape offences that have yet to be assigned an outcome for that period.

Figure 8: The number of finalised outcomes and outcome rates recorded by forces in England and Wales for year ending March 2020

Source: Home Office published data

Please note that the figures above relate to outcomes assigned to rape offences in the year ending March 2020. For the year ending March 2020, 19,053 rape offences (34 percent) have not yet been assigned an outcome.

When the victim doesn’t support the case (Outcome 16)

In more than a third of the cases we reviewed (120 cases), the victim didn’t support the investigation from the outset. There are many understandable, and complicated, reasons why victims may not support police action. These include:

- fear of the criminal justice system;

- the need to move on;

- negative effect on mental health and well-being; and

- lack of support from family, friends or employers.

Inspectors found that in cases not supported by the victim from the start, the details of the offence were often vague, resulting in a lack of investigative opportunities. Although this doesn’t rule out an investigation progressing, it does make it extremely difficult to gather the evidence and information needed. It is unlikely that the evidential threshold will ever be met without the victim’s co-operation.

Figure 9: The outcome used to finalise the case and whether the victim supported it initially

Source: Data taken from our case file review analysis (344 files). In eight files, whether the victim supported at the beginning was not applicable; these aren’t included in this chart

The current system doesn’t tell us at what stage of the process the victim withdrew their support. Being able to distinguish between the victim who doesn’t support the investigation from the outset and one who later withdraws their support is important. It would allow the force to analyse this information to understand the reasons victims may withdraw support and, where it is able, to adapt its approach to investigations to provide greater opportunities for better outcomes and victim care.

The help that a victim needs may depend on their feelings about supporting a prosecution. A victim who doesn’t support police action from the start may have different needs to one who withdraws at a later stage. Equally, a victim who indicates a lack of support from the outset may change their mind if they have received support that is targeted to their specific circumstances. Although some forces could identify when the victim withdrew support, there is no national mechanism to do so. So an opportunity to gather and use data in a focused way is lost, as is the opportunity to understand why the victim withdrew, and what factors could have helped them to remain engaged.

Better data would also help the public to understand these investigations. The current outcome codes rely more on process and fail to give a full picture of a victim’s experience. Furthermore, without thorough and scrutinised information on why cases are not progressing, forces are unable to assure either themselves or the public that their decisions to take no further action are correct.

Recommendations

Recommendation 3

Police forces should collect data to record the different stages when, and reasons why, a victim may withdraw support for a case. The Home Office should review the available outcome codes so that the data gathered can help target necessary remedial action and improve victim care.

Quality of police decision-making

“It all happened really quickly – which wasn’t necessarily a good thing, because it seems the police expected it to be NFA’d from the outset, and there was minimal investigation.”

Quote from a victim of rape

In most of the case files we reviewed, the police decision to take no further action (NFA) was not inconsistent with the Code and relevant guidance. But, as discussed above, this outcome potentially masks a range of factors that could have contributed to the eventual decision and influenced the final outcome. We also found that 37 of the 352 cases had outstanding lines of enquiry that should have been completed before they were finalised. Further, in almost a third of the cases, the victim withdrew their support and potential evidence could have been lost if the victim had decided they were able to re-engage with the police at a later stage. We found some evidence that this was less likely in the specialist teams.

Our inspectors assessed that 7 of the 352 police decisions should have been referred for CPS advice. We also found that in 7 of the 90 CPS decisions the police should have decided to take no further action rather than refer the file to the CPS.

Worryingly, we found that some cases were closed quickly when a case involved complex features, such as a victim with poor mental health or alcohol or drug dependency, or who was particularly vulnerable and unsure whether they wanted to support an investigation.

Case study

The victim, who was alcohol dependent, reported to their support worker that someone they knew had tried to rape them. When the police attended, they noted the victim had injuries, and used an early evidence kit to secure any potential forensic evidence. The victim was taken to a safe place for the night. But officers didn’t speak to the suspect when they attended, even though they were at the address. The suspect was allowed to leave. The victim was reluctant to support the case, blamed herself throughout, and didn’t want to give an account via a video interview. Although the victim was identified as vulnerable, the police didn’t consider getting an intermediary to help and support the victim through the process. The case was filed as ‘Outcome 16’ – no further action – as the victim didn’t support it. Although safeguarding was put in place for the victim, the police didn’t consider the risk that the suspect posed to other women.

Case study

The victim was in prison when she reported a rape that had happened before she was sentenced.

There seemed to be some inconsistencies in the disclosure. The victim was never spoken to by the police, nor was the alleged suspect. In finalising the case, the detective inspector commented that “It is clear that he (suspect) would deny any allegations that are made”.

It wasn’t clear whether any contact was ever made with the victim, due to her moving from one prison to another. The case was finalised (Outcome 15) with no meaningful investigation taking place.

By contrast, our case file assessments showed examples of the police being more likely to continue the investigation and pursue lines of enquiry if the victim didn’t have complicated needs or vulnerabilities.

We found that different levels of supervisor were authorised to finalise cases as no further action. In some forces, the detective sergeant could authorise a case to be finalised; in others it was the responsibility of the detective inspector.

In focus groups of investigators and interviews with operational leads, we heard that although decisions are based on each individual case, the decision to take no further action depends on the detective inspector or the detective sergeant having a briefing from the sergeant or the investigator.